Art and Science

When you enter the Quaker meetinghouse that constitutes Stroud Water Research Center’s conference and event room, you encounter Leonid’s world — a world of soft oil paintings characterized by great canvases of gray, blue and green waters blending imperceptibly into similarly colored skies.

Subtle colors portray reflected sunlight, an approaching storm, phosphorous on a wave. The humans in the paintings are sketchily drawn, at once dwarfed by and in harmony with the world of sky and water that envelops them.

Known simply as Leonid, the artist Leonid Berman spent much of his life painting pictures of people who make their living on the water. Born into a well-connected Jewish family in St. Petersburg near the end of the last century, Leonid escaped from Russia just after the Bolshevik Revolution and survived World War II as a prisoner on a labor gang in France. He emigrated to the United States after the war and became a close friend of the Stroud family.

At his death in 1976, he left half his estate, which consisted almost entirely of his paintings, to the Stroud Foundation.

Throughout his wandering, ever-curious life, Leonid traveled all over the world, painting Norman mussel gatherers, Asian boat handlers, Mediterranean sailors and Maine lobstermen. The vast expanses of water and sky give a sense of calm to his oils that stands in stark contrast to the lives of the seafarers he paints — as if the artist who had seen such oppression from the hands of humans sought transcendence in the serenity of the natural world.

The paintings provide an apt backdrop for the Stroud Center meetinghouse. It isn’t just the centrality of water to both the artist and the scientists. It is that, beneath the calm surface of both painting and laboratory, lies a barely concealed intensity born of a commitment to their work.

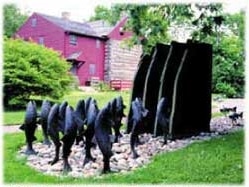

Art has played an essential role at the Stroud Center from the beginning, and Leonid is not the only painter whose work is on view here. The Stroud family are both lovers and collectors of art, and they have provided their own works and quietly nourished a belief in the importance of art to the scientific process. Over the years, the hall onto which the staff offices open has become a gallery where changing shows of painting, sculpture and photography are regularly put on display.

The commitment to art has helped build an environment that encourages contemplation and innovation.

The staff knows that they might not like, nor at times even understand, what they find hanging across from their offices, but they are eager to encounter it. They have learned that their initial inability to grasp an abstract painting is not so different from other people’s inability to grasp the arcane language of their own field.

And they have come to believe that the two worlds are not as far removed as many think — that the creative process is as much a part of the science at the Stroud Center as it is of the art.

Learn More About Our History

The Beginning | The Watershed | Landmark Research | Art and Science | Road to Independence | Building Blocks

Celebrate Stroud Water Research Center’s history — from its humble beginning in Joan and Dick Stroud’s garage to a world-renowned freshwater research institution — with our anniversary book, The First Fifty Years.