Green Roofs

From Humble Sod Houses to High-Tech Green Buildings

While green roofs like that of the Moorhead Environmental Complex are part of a recent innovation that began in Germany in the 1970s, the history of green roofs goes back for centuries.

Originally necessitated by a scarcity of building resources, green roofs were used extensively in Scandinavia and Iceland. Immigrants from those areas took the building methods with them as they moved into the American West, creating sod houses in the nearly tree-free landscapes of the great prairies.

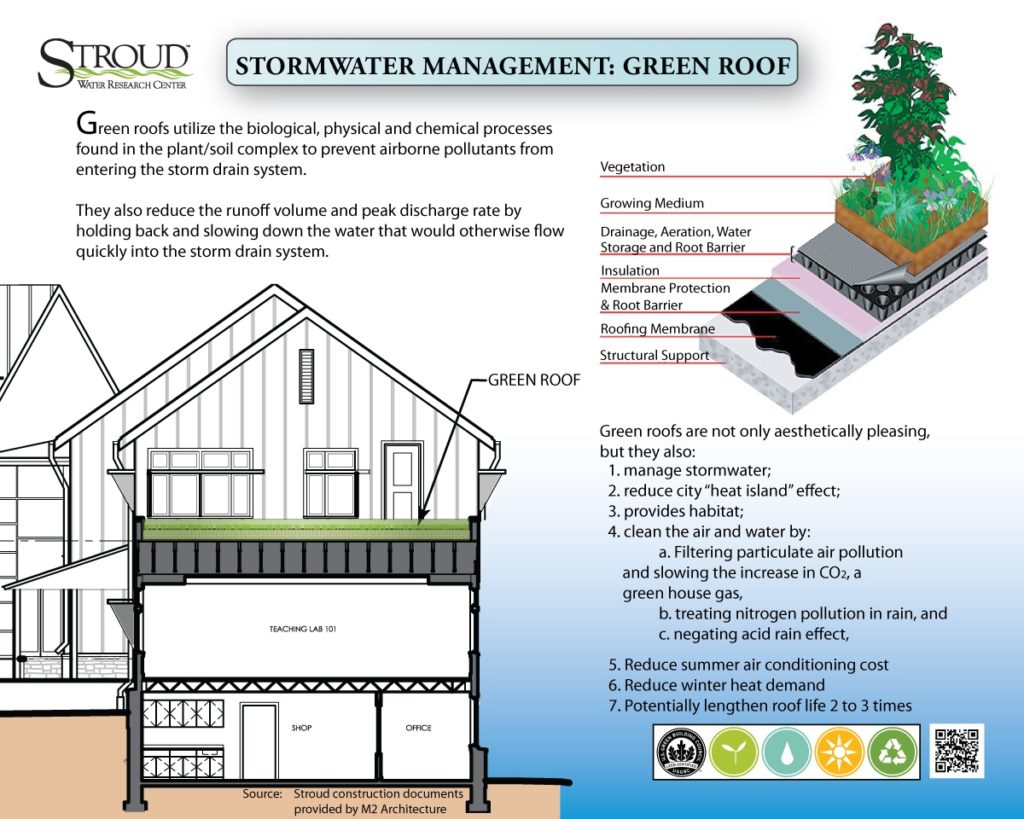

Modern green roofs utilize plant species that tolerate heat, dry conditions, shallow soil, and minimal maintenance.

Source: http://www.greenroofs.com/Greenroofs101/history.htm

Protecting White Clay Creek

We are pleased that our green roof is part of a stormwater management strategy that offers benefits to White Clay Creek (WCC), which flows at the edge of our campus and has been the focus of our research since 1967.

The WCC watershed encompasses parts of Chester County, Pennsylvania and New Castle County, Delaware. It flows into the Christina River near Newport, Delaware, which in turn, flows into the Delaware River near Wilmington. WCC is composed of three main branches in Pennsylvania (East, Middle, and West) and three main tributaries in Delaware (Middle Run, Pike Creek, and Mill Creek).

In 2000, Federal legislation designated WCC and its tributaries as a National Wild and Scenic River signifying it as possessing outstanding scenic, wildlife, recreational and cultural value. That marked the first time an entire watershed — rather than just a section of river — had been designated.

Approximately 17% of the watershed is protected open space providing a variety of habitats to a rich diversity of fish and wildlife: 21 species of fish, 33 species small mammals, 27 species of reptiles and amphibians, and over 90 species of breeding birds.

It is also a cultural and historic location that was originally settled by the Lenape Native Americans and presently has 38 properties on the National Register of Historic Places. In addition, nearly 130,000 people get their drinking water from the WCC and the Cockeysville aquifer that underlies portions of the watershed.