By Diane Huskinson

Let it Salt

Following record-breaking snowfall this winter, many states, especially along the East Coast, remedied icy road conditions with greater amounts of road salt (sodium chloride) and brine (magnesium chloride).

District 6 of the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT) reports spreading more road salt this winter than in the past 33 years. And District 9 reports using more brine. It’s part of a growing trend.

According to a report released by the USGS National Water Quality Assessment Program, the application of salt as a deicing agent has increased dramatically since the 1950s.

While sodium chloride and magnesium chloride improve road conditions by effectively melting ice and preventing its buildup on roads, these salts are also ending up in our streams and rivers. As are other sources of salts:

- Residential: Many rural residents use water softeners to reduce the hardness of their well water prior to domestic use. Salt use in water softeners typically finds its way through a septic system to a drain field and ultimately is delivered to ground and surface water resources.

- Sewage treatment: Raw sewage contains salt. Sewage treated by wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) is permitted to be discharged to streams and rivers, but most conventional WWTPs do not substantially remove salts during treatment.

- Industry: Salts are used in many industrial processes such as in the production of chlorine and sodium hydroxide, metal, paper, textiles and petroleum.

- Agriculture: Some agricultural products, such as composts and fertilizers, contain salts.

It Gets Worse

Streams naturally flush water, salty or not, out to sea. Fresh groundwater, where some drinking water comes from, recharges streams. However, of added concern to scientists are early signs that groundwater sources are also getting saltier.

During a six-year study of New York’s drinking water supply sources, Stroud Water Research Center researchers found that many streams in New York had elevated chloride concentrations in summertime stream water samples. Of the 110 streams studied, those with elevated chloride concentrations were also downstream of higher densities of roads, residential households and WWTPs.

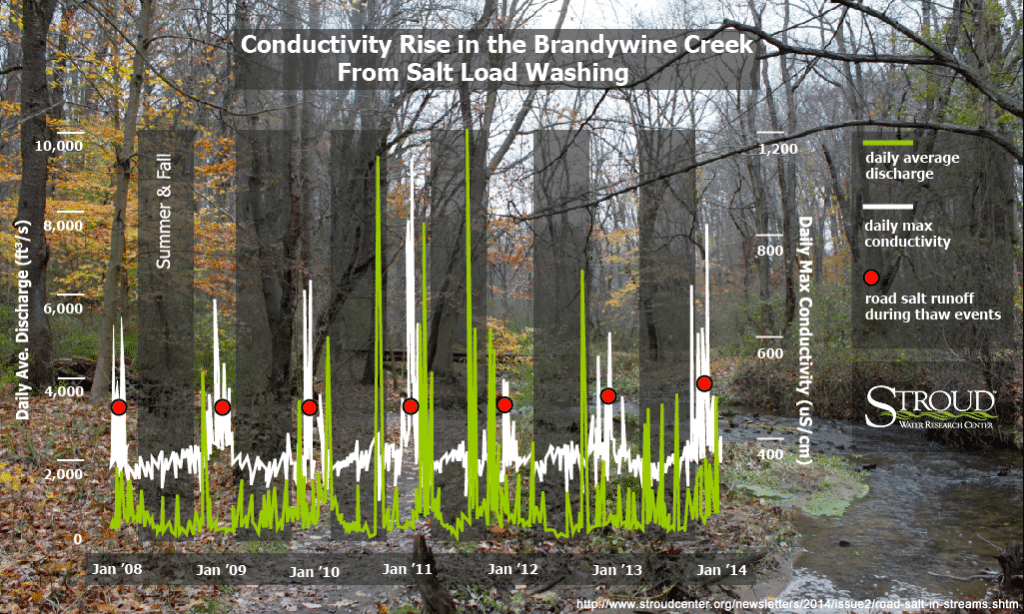

In many streams in the Schuylkill River watershed, a tributary of the Delaware River in Philadelphia, the Stroud Center also observed salt concentrations have increased over the last 15 years. Because these observations come from water samples collected during baseflow conditions (i.e., not stormflow), scientists think the groundwater sources of stream flow are becoming saltier, albeit much less saltier than seawater.

“Some of the road salt and brine that’s used on land flushes into streams and runs through, but some is absorbed into the ground. Once groundwater becomes salty, it slowly discharges that salty water. But it takes time. The continued use of road salt and brine, especially in high quantities, threatens the quality of our groundwater as well as our streams and rivers.” Research Scientist Dave Arscott, Ph.D.

Research Scientist Dave Arscott, Ph.D.

Identifying Salty Streams in the Northeast

Studies beyond the Stroud Center have also shown the increasing saltiness of freshwater sources, or what scientists call salinization, in the Northeast.

A 2003 study revealed that over fifty years of road-salt application in the Mohawk River watershed in New York resulted in a 130% increase in sodium and a 243% increase in chloride.

In 2005 another study reported that salt concentrations in several streams in Maryland, New York and New Hampshire were increasing. Sodium concentrations were very high during winter, which researchers would expect, given the road salt application. However, summertime salt concentrations were also high, remaining at nearly 100 times the concentrations in nearby forested streams, where human inputs would be minimal.

Good Salt, Bad Salt, and How Much?

While brine is growing in popularity since less is needed to improve road conditions, Arscott warns brine is also more toxic than road salt for some organisms, and “we don’t have enough information about its toxic effects to really say brine is better.”

As recommendations, the U.S. Clean Water Act ultimately relegates the decision to implement standards for salt applications to each of the fifty states. Pennsylvania is in the midst of defining and implementing a chloride standard for its waters, whereas several other states — including Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Virginia and West Virginia — have already adopted criteria established by the Environmental Protection Agency in 1988.

Currently, no special guidance is given for permitting salt applications or industrial effluents known to include significant amounts of chloride derived from the more toxic nonsodium salts. “This point should be more rigorously discussed,” says Arscott, “since magnesium chloride is becoming a more common road deicing agent in the Northeast.”

Getting the Facts Straight

For businesses, landowners, policymakers and individuals to make informed decisions about the use of salt, new research into its effects on freshwater sources is needed. The Stroud Center is studying the toxic effects of salts on mayflies because the loss of mayflies is an early indicator of degraded conditions in streams and rivers. A recent study led by Senior Research Scientist John Jackson, Ph.D., looked at how mayflies responded to produced water versus sodium chloride when mixed with stream water. (Listen to a one-minute podcast.)

“We need to think critically about salt use,” says Arscott, “It’s much easier to make freshwater salty than it is to make salty water fresh.”

Sources:

- Pennsylvania Department of Transportation 2012-2013 Winter Maintenance Guide

- Salt use at record pace this woeful winter, PennDOT says

- Chloride in Groundwater and Surface Water in Areas Underlain by the Glacial Aquifer System, Northern United States

- Long-term trends in sodium and chloride in the Mohawk River, New York: the effect of fifty years of road-salt application

- Increased salinization of fresh water in the northeastern United States