Students and educators in the Shenandoah Valley explore watershed science with the Stroud Center’s mobile lab, learning how their actions impact the Chesapeake Bay.

John Denver called it heaven. Native Americans are thought to have called it “River Through the Spruces.” The Shenandoah Valley is a mostly rural landscape hugged by densely forested mountains to the east and west. Winding through it is a river by the same name, which runs northeast until it meets the Potomac, whose waters eventually flow into the Chesapeake Bay.

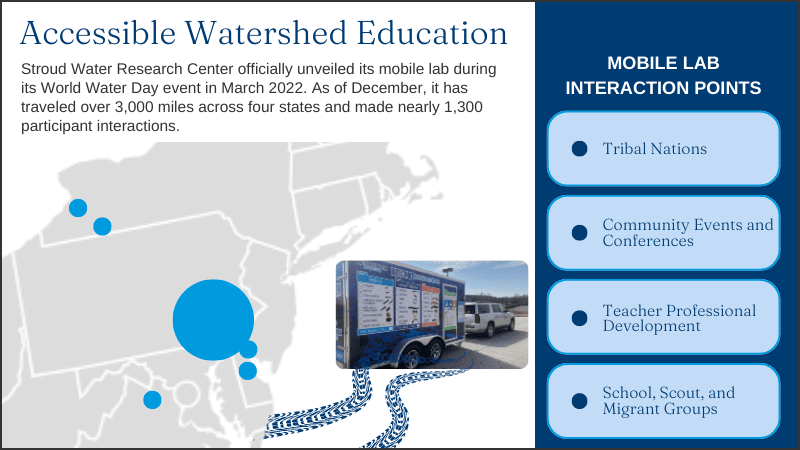

Not far from home, students from James Wood High School met Stroud Water Research Center educators on the banks of a tributary to the Shenandoah River last spring. The team had driven 160 miles, the Watershed Education Mobile Lab in tow, from southeastern Pennsylvania to lead the students and a group of educators through a journey of scientific discovery.

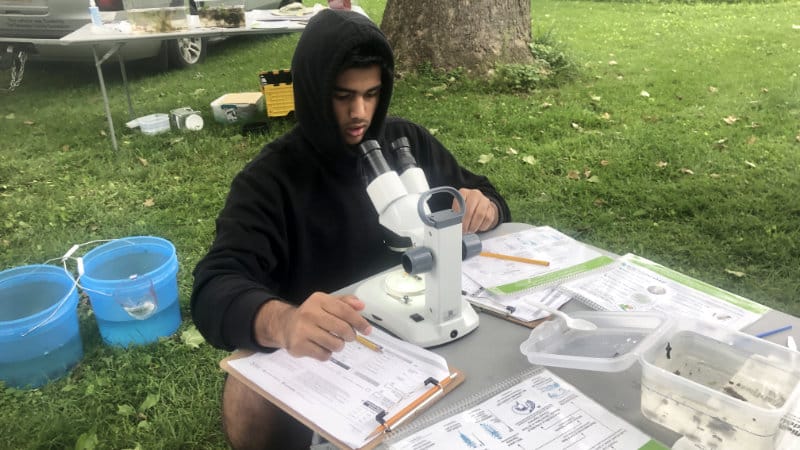

During one of several hands-on activities to learn about watershed health, the students huddled around an outdoor lab bench. As they sorted and identified insects from the stream, they found stoneflies, dragonflies, and other species that love healthy waters. Their findings were consistent with the setting. Preserved open space at Shenandoah River Campus at Cool Spring Battlefield provides natural habitat and helps keep the stream healthy.

Virginia educators and an ecologist with the Fairfax County Department of Public Works attended the outdoor field study too. They observed the Stroud Center’s approach to accessible and meaningful watershed education and learned how to repeat these experiments in their local watersheds.

In Frederick County, where James Wood High School is located, students and teachers will be able to investigate water quality in the creeks near their school campus — the Opequon and one of its tributaries, the Abrams. When they do, they may not find as many of the bugs that are sensitive to degraded stream conditions. Pollution from sources including agriculture has impaired the health of both streams and the surrounding Opequon watershed, which crosses into West Virginia. The high pollution levels make the watershed an important one in the Chesapeake Bay cleanup effort, as the water flows into downstream communities.

Kelley Aitken, Ed.D., supervisor of science and visual art for Frederick County Public Schools, says that by getting students into the field to collect data and monitor their local watersheds, they can see their impact on the Chesapeake Bay: “What we do in Frederick County does impact the bay, but when talking about it to our students, who may or may not have ever been there, it’s very removed from them.”

Aitken says that field experiences such as those offered through the Stroud Center’s mobile lab help students understand how their actions impact the bay and help to advance environmental literacy.

Globally, American students have scored below average in environmental literacy — the knowledge and skills necessary to make informed decisions affecting air and water quality, wildlife habitat, climate change, and more. They are also less likely to feel responsibility toward water shortages compared to other environmental issues such as nuclear waste, energy shortages, and species extinction.

Venicia Ferrell, Ph.D., research associate at The Center for Educational Partnerships at Old Dominion University, says meaningful watershed education experiences like those the Stroud Center provides through its mobile lab are needed for students to develop environmental literacy: “When you’re in a classroom you can only make so many observations and inferences. It’s a very limited environment. When you’re outside, there are hundreds of observations and inferences that can be made just from one site to the next. In education, we spend a lot of time talking about how to critically think, but not a lot of time doing it. [Outdoor experiential learning] gives students the opportunity to critically think.”

Aitken and Ferrell are a collaborative duo working across a distance of more than 200 miles to enhance environmental literacy and connections between students throughout the Chesapeake Bay watershed — Aitken from the freshwater habitats of northern Virginia and Ferrell from the brackish waters of the bay.

Ferrell, who worked with the Stroud Center’s Tara Muenz to bring the mobile lab to Virginia, oversees the Southeastern Virginia Environmental Education Consortium. Coordinated by The Center for Educational Partnerships, the consortium brings together six public school systems to promote environmental literacy. She says she hopes to secure funding that would allow Frederick County and bay-area students to travel to each other’s waterways.

“One of the reasons this kind of interaction is needed is because the school districts are urban, suburban, and rural. The districts serve very diverse populations, and the types of projects that they engage in will differ based on their local environment. For example, in Frederick County, students can raise and release trout. Closer to the Chesapeake Bay, the students raise and plant oysters on sanctuary reefs, and they grow eelgrass in their classrooms and plant it in their local waterways. These are just a few projects that students participate in to restore the bay,” says Ferrell.

In the spring, Stroud Center educators will take the mobile lab to the bay area to provide watershed education and professional development for students and educators from those schools.

Aitken adds, “It’s hard for students to see their individual actions having broader consequences, so creating these connections enables them to see how they are dependent upon one another.”

Want to help us expand environmental literacy among children and adults? Make a tax-deductible gift today. All donations until December 31, 2022, will be matched 1:1 by our Board of Directors, up to $100,000!