With help from Stroud Water Research Center, community scientists and watershed groups are measuring the impact of salt pollution on fresh water and taking action.

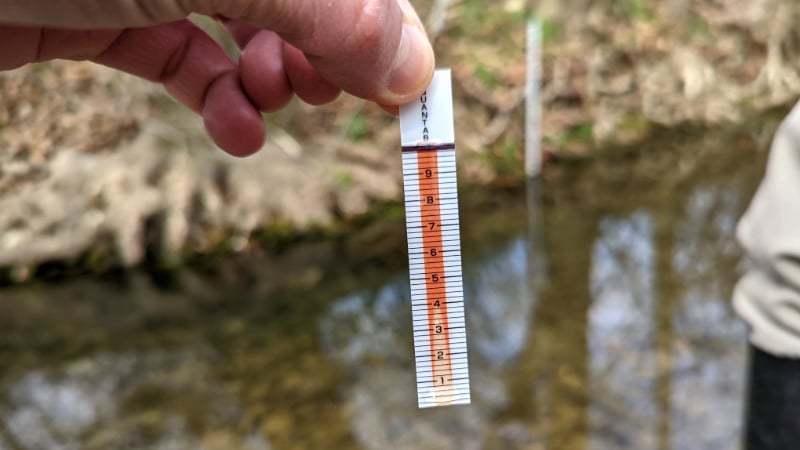

Months after the icy conditions that brought the spreading of deicer and salt spikes in Tookany Creek that were saltier than seawater, an army of volunteers descended upon dozens of sites in small streams that feed the Delaware River. They were on a mission to discover how widespread, severe, and long-lasting the salt contamination is in their local communities, as well as in the larger Delaware River watershed that provides drinking water to more than 15 million people.

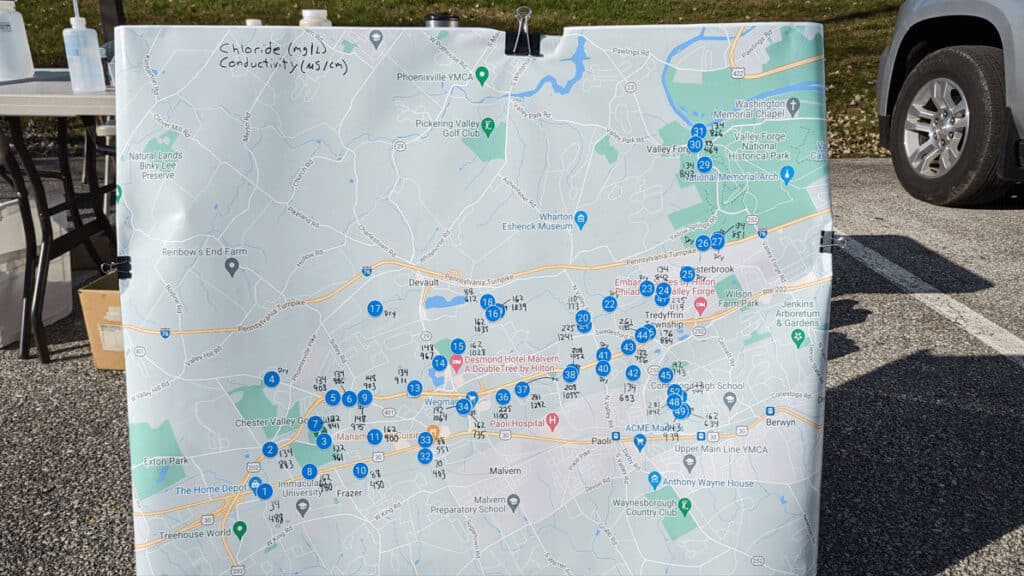

Called snapshots, these single-day synoptic sampling events create a high-resolution picture of stream health. They eliminate the variable of changing seasons and weather as volunteers measure, within the span of an afternoon, how salty streams are throughout a watershed or region. The snapshots also can be used to gain evidence of long-term groundwater contamination and can help to identify specific sources of salt pollution.

Stroud Water Research Center has helped many of its partner organizations to gather high-quality data during snapshots. The snapshots fill in water quality data from areas not captured by USGS streamgages or the Stroud Center’s EnviroDIY network, both of which require some expense and ongoing maintenance.

These moments frozen in time reveal an alarming trend. While some sites had relatively low chloride or conductivity, another measurement of salt, others are in trouble. All of the snapshots have been conducted outside of peak season for road salt application. Yet some streams still tested high, indicating so much salt has been applied in previous winter seasons that it has contaminated the groundwater.

Willistown Conservation Trust (WCT) in partnership with Darby Creek Valley Association (DCVA) held its first snapshot in early November 2022. Within two hours, the group had collected samples from 19 previously unstudied sites in the headwaters of Darby Creek.

Lauren McGrath, director of the Watershed Protection Program at WCT, says, “Darby Creek is definitely very impaired, but it’s not consistent throughout the entire watershed. There are still areas that are really lovely. Those sites we should prioritize protecting and amplify that they exist.”

Not so lovely is the pollution hotspot her group identified in a developed area near a SEPTA train station in Chester County. “We are working with our volunteers to continue to understand where the problem spots are,” says McGrath.

At the end of the snapshot event, McGrath displayed the findings on a large map of the watershed for all the volunteers to see.

Deirdre Gordon, who maintains an EnviroDIY Monitoring Station, volunteered for the snapshot. So did her husband, Lloyd Cole. Commenting on what she saw, Gordon says, “Some were where you would expect, but some were not. That was very interesting to see the big picture. It has certainly made us very aware of road salt. Yes, I like to have the roads treated. I don’t want to slide off the road, but when you see extra salt dumped somewhere, I realize now how potentially damaging that is.”

Charlie Coulter, a Master Watershed Steward who monitors data from 19 EnviroDIY Monitoring Stations, also participated in the Darby Creek snapshot. He says he frequently talks to friends and neighbors about how salt ends up in streams. His motivation: “My grandkids. I can see where it’s going, and I don’t like it. Eventually, we’re going to run out of clean water. Things have to change on a big level.”

In general, water quality is relatively poor where Darby Creek flows through highly developed areas. The more roads, walkways, and parking lots, the more deicer.

Pete Goodman, environmental chairman and longtime member of Valley Forge Trout Unlimited, expressed his concern that the continued and intense application of salt, as well as new development in his area, may worsen salt pollution in Valley Creek and threaten food webs that support local fish populations.

Goodman worked with the Stroud Center’s David Bressler to design his group’s first salt snapshot in November and create some educational materials.

Some of the sampled sites were unexpectedly high — as much as 300 milligrams of chloride per liter of stream water. To prevent chronic toxicity, streams should measure below 230, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. Some sources set standards even lower. Current research suggests levels as low as 50 milligrams per liter can impact sensitive aquatic life and disrupt food webs. In the Delaware River Basin, natural chloride levels are in the range of 5 to 20 milligrams per liter.

Bressler and Goodman charted 60 years of rising chloride concentrations in Valley Creek using historical USGS data. In 1961, chloride levels matched natural conditions. By the early 1970s, they had risen to the stress threshold for sensitive species and chugged along consistently until the mid ’90s when there was another sharp increase. Then, the early 2000s brought a meteoric rise to levels of chronic toxicity.

The rising salinity of Valley Creek follows the trajectory of road salt use in America. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, road salt use today is more than 20 times greater than in the 1950s.

Goodman has been using the data to warn Trout Unlimited members and local environmental advisory councils about the impact of road salt on Valley Creek.

“If we don’t do something about it pretty quick, we will have a stream that’s pretty much dead,” Goodman says. He means biologically dead and explains that when smaller and more sensitive species like mayflies are wiped out, “it can have an avalanche effect. The whole food chain could collapse.”

Goodman says he and other anglers have observed a decline in insect populations in Valley Creek, and multiple threats may be at play, possibly compounding one another. Climate change and urbanization, for example, result in warmer temperatures that increase the toxicity of salt in streams.

Goodman admits that not everyone shares his interest in protecting fish. “I’m a tree hugger and a fish kisser, and I like it all,” he says, but he cautions that there’s more at stake than recreational fishing: “It could mean the cost of drinking water goes up, the cost of auto repairs, taxes going up because infrastructure is rotting. People need to know that salt use comes at a cost. And there aren’t any good alternatives. We have to use less.”

As the volunteers amass more data, scientists are analyzing the collective impact of salt pollution across the Delaware River watershed. John Jackson, Ph.D., co-leads the Stroud Center project — funded by the William Penn Foundation as part of its Delaware River Watershed Initiative — that provides partner organizations with technical support for stream monitoring. He says, “We’ve tried to standardize the data so that it is comparable between sites and can supplement the EnviroDIY data. When we put this all together, it’s going to start a conversation at the Department of Environmental Protection. Nobody has generated those data yet.”

How to Reduce Your Salt Use

To learn about some methods for reducing road salt, check out these fact sheets created in collaboration with our friends at Tookany/Tacony-Frankford Watershed Partnership, Pennypack Ecological Restoration Trust, and Valley Forge Trout Unlimited.

Persistence is the Salt of Stream Stewardship

Read how a Master Watershed Steward took action after she observed inadequately protected road salt piles during winter in southeastern Pennsylvania.

An Interview With Pete Goodman

Wisdom and advice on watershed protection from a prodigious environmental leader you’ve (possibly) never heard of.