How Penn State Extension Launched One of the Most Successful Volunteer Training Programs in the U.S. and Revived Struggling Local Watershed Groups

Penn State Master Watershed Stewards have time and again proven to be some of Stroud Water Research Center’s most knowledgeable, active, and consistent volunteers. Through their partnerships with the Stroud Center and other organizations, they plant trees, remove invasive species, collect water quality data, and communicate ways local governments can better manage water resources. The Swiss Army knife of watershed volunteers, they carry a variety of skills to meet local needs.

This year, Penn State Extension welcomed its 11th cohort of stewards into the program, which has become one of the most successful in the United States, according to State Coordinator Erin Frederick and Steering Committee Chair Rebecca Hayden.

Hayden recalls, “I remember Erin texting me from a national conference four or five years ago.” Referring to coordinators from other states, she says, “They all wanted her advice on how to run their programs, and I thought that was super funny because our program was relatively young.”

The Struggle to Find Volunteers

Frederick, Hayden, and Jim Wilson, who was the watershed specialist for the Northampton County Conservation District at the time, launched the program after a conversation over breakfast.

The colleagues had gathered for a meeting of the Watershed Coalition of the Lehigh Valley. As they discussed the struggle many watershed associations faced in finding volunteers, Frederick, then the new Lehigh Valley coordinator of the Master Gardener Program, said the gardener program was so popular it had a waiting list. It was a lightbulb moment.

Hayden, now a project specialist with the Pennsylvania Infrastructure Investment Authority, says, “Erin was honing in on the fact that a structured program with credentials felt very different to people.”

Frederick and Hayden knew from their time working at the Lehigh County Conservation District for more than a decade prior that watershed associations were relying on only a few people who were getting burned out.

“There wasn’t any new blood,” Hayden explains.

Frederick’s idea was to create a program that trains would-be volunteers in the basics of watershed science and management, including topics such as groundwater, stream ecology, wetlands, invasive plants, water recreation, stream restoration, and stormwater management.

Modeled after the Master Gardener Program, the Master Watershed Stewards Program provides structure and support through county or regional coordinators, as well as opportunities to continue learning and build relationships.

“In Bucks County,” Hayden says, “we had a brunch-and-boat where we had brunch, paddling, and an educational program. Sometimes we’ll go on hikes or have pizza parties.”

Hayden says the program teaches stewards about not only watershed science but also “who to reach out to if they want to do something or if they need additional resources.”

The Stewards and the Stroud Center Become Partners

The Stroud Center has been part of the program since the beginning. John Jackson, Ph.D., David Bressler, Shannon Hicks, and Rachel Leonard have led workshops for the stewards.

Frederick says, “When our trainees come to Stroud, it levels everything up for them. They feel like they are at the place where cutting-edge watershed science is happening.”

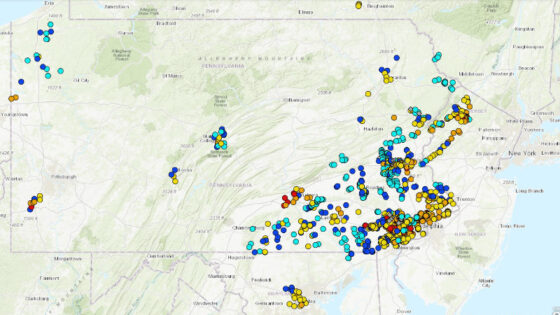

Charlie Coulter is among them and has supported the Stroud Center’s community science project in the Delaware River watershed. The project uses EnviroDIY Monitoring Stations, maintained by volunteers and watershed organization staff, to collect water quality data from a network of small streams throughout the watershed.

Coulter supports other stewards in maintaining 19 stations for Willistown Conservation Trust, Darby Creek Valley Association, and First State National Historical Park in Delaware. A fly fisherman, beekeeper, and retired instrument technician, he says he became a Master Watershed Steward because of his interest in conservation.

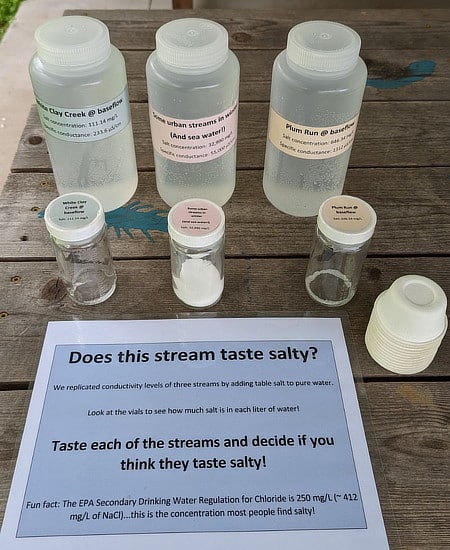

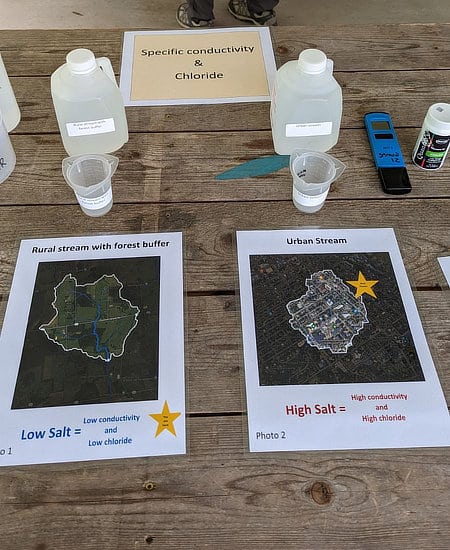

“Being involved with Trout Unlimited, I was kind of aware of what is good and bad for the stream,” he says, “but looking at all the data, you start to see a lot of different things that you never realized. Piles of salt that are laying in parking lots and what kind of an impact they have.”

He says he recommends volunteering to other people: “It’s beneficial. You feel good. You feel like you’re part of it. You’re actually doing something.”

Making an Impact

Statewide, the stewards have worked to restore stream health and wildlife habitat by planting more than 50,000 trees and shrubs and converting more than 50 acres of lawn into meadow.

Each year, the program trains 140 to 160 new stewards, all of whom must complete ongoing training and volunteer service hours.

The program now serves 42 of the state’s 67 counties, recently including its most populous: Philadelphia County.

In the birthplace of the program, the Lehigh Valley, there’s a notable concentration of stewards who have risen to positions of leadership and leaders who have become stewards.

Hayden is also president of the Watershed Coalition of the Lehigh Valley and says that the coalition’s membership is comprised of 12 watershed associations, all of which have at least one Master Watershed Steward on their boards of directors. Half of the board presidents are trained stewards, she says.

Further south in Montgomery County, Ross Snook is a township supervisor for New Hanover Township, chair of the local environmental advisory board, and a Master Watershed Steward. Last year, he worked with the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection to standardize the collection of stormwater and water quality data and to create a GIS-enabled website. He says he hopes the website will eventually allow online public access to stormwater data from across the state, making it easier for supervisors like him to work with neighboring townships to better understand and meet stormwater requirements (known as MS4) at a watershed scale.

Hayden says, “What I find personally rewarding is watching people who want deeply to make a difference. They had no idea how, and they found themselves coming out of this program with the tools, information, and connections to make a difference. They are learning how to engage with their local communities. They are learning how to manage projects and people and becoming effective environmental advocates. That’s the thing that makes it worth it to me — to see people not just empowered but also effective.”

Get Involved

If you are interested in becoming a Master Watershed Steward, explore the program website or contact your county coordinator.