By Jennifer Merrill, Ph.D.

Many of us experienced the intense heat wave in mid-June 2024 and again in early July. Have you ever wondered about the immediate and long-term effects of such extreme weather on our streams and rivers and how it impacts the delicate balance of life in the water?

Temperature Can Be a Pollutant

One remarkable feature of water is its high heat capacity, or how much energy is needed to change its temperature. That’s why it takes water so long to boil and why air and water temperatures vary from each other in the environment. Most stream life is cold-blooded, meaning their metabolic rate increases with temperature, so this moderation of temperature swings is an essential feature of freshwater and marine habitats.

Warmer water holds less oxygen, so temperature is critical to stream life. In freshwater streams and rivers, temperature can be a pollutant that diminishes the quality of habitat, making the survival of the stream’s life more uncertain.

Heat Stresses Stream Life

So, how hot did our streams get during June’s heat wave? Did we see immediate impacts on fish or aquatic bugs?

Yes, of course, stream temperatures increased. In one section of White Clay Creek next to Stroud Water Research Center, water temperatures reached 74 degrees Fahrenheit. That’s high enough to affect some fish and aquatic insects in the stream.

Brown trout in White Clay Creek can become stressed at about 68 degrees Fahrenheit and cannot tolerate water above 77 degrees. More sensitive native brook trout prefer cooler temperatures, generally below 59 degrees, but can tolerate temperatures up to 72 degrees for short periods.

A Long-Term Study Yields Answers

How might we help the stream habitat remain hospitable to fish and insects? We’ve been conducting a 35-year research project to find out. This study is crucial to understanding the effects of temperature on aquatic life and the benefits of reforestation, and it provides invaluable insights for conservation efforts.

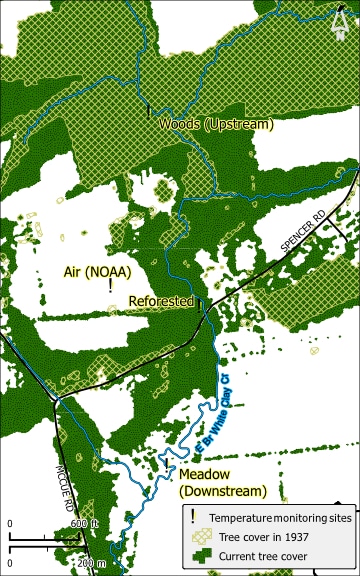

When the Stroud Center was established in 1967, it began in a tobacco barn near the banks of White Clay Creek. The land surrounding it was farmland. Upstream, the forest had been cut for lumber, pasture, and cropland during colonial times but had regrown and was considered mature, with fully grown trees reaching over and sheltering the creek.

The stretches of creek adjacent to and downstream of the Stroud Center were open to the sky, heating and cooling without the protection of a forest canopy. Stroud Center scientists designed an experiment to measure the changes in a stream as the land around it was reforested.

A streamside forest, or riparian buffer (a strip of vegetation along the banks of a river or stream that helps protect the waterway from the impact of adjacent land use), was installed in 1989. Thirty-five years later, those trees protect and sustain life within White Clay Creek.

One of the ways they do that is by modifying the temperature of the stream’s water.

A Look at the Data

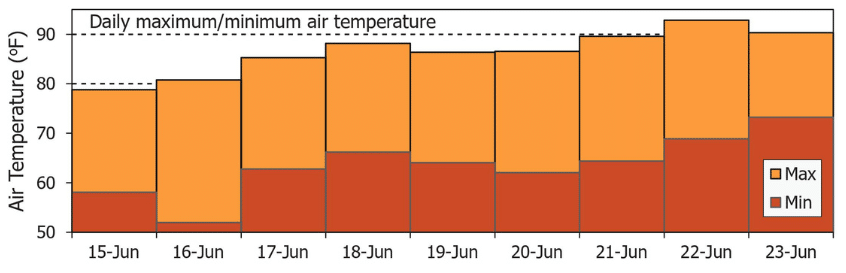

The graphs show temperature data for the three White Clay Creek locations. First, we see the air temperature recorded each day. Also included are the nighttime minimum temperatures.

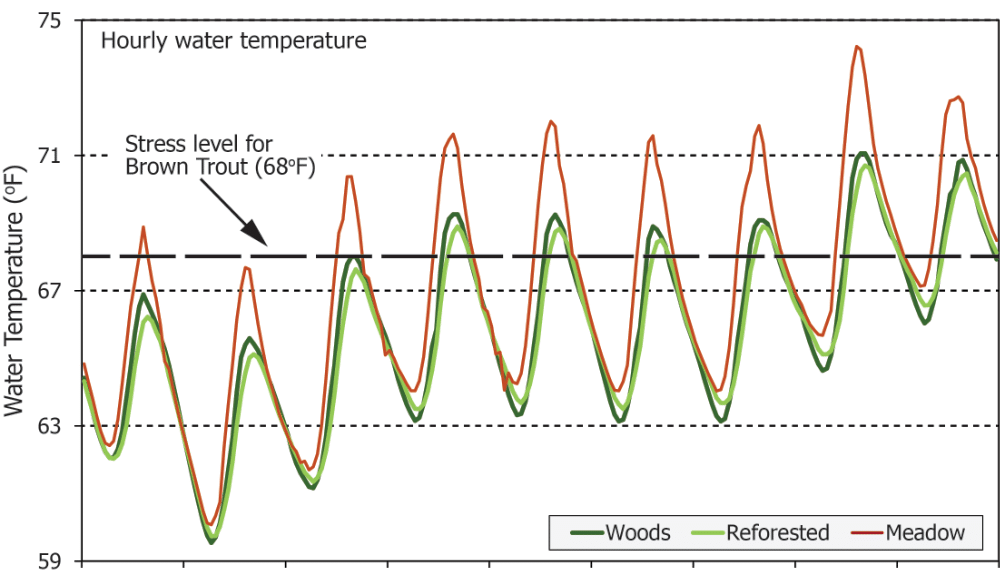

The second graph shows water temperatures at different locations in the creek. Stream water flows from the uppermost station in the old forest (woods), through the reforested site, and into the open meadow.

The most apparent trend is the daily temperature cycle in the different locations.

- Water temperature swings about 4.5 degrees Fahrenheit daily in the meadow and between 2 and 4 degrees in the forested stream sections.

- The meadow reach heats up earlier and stays warmer at nearly all times, even at night.

- The daily temperature change between afternoon highs and nighttime lows is always less in the forested sections of the stream.

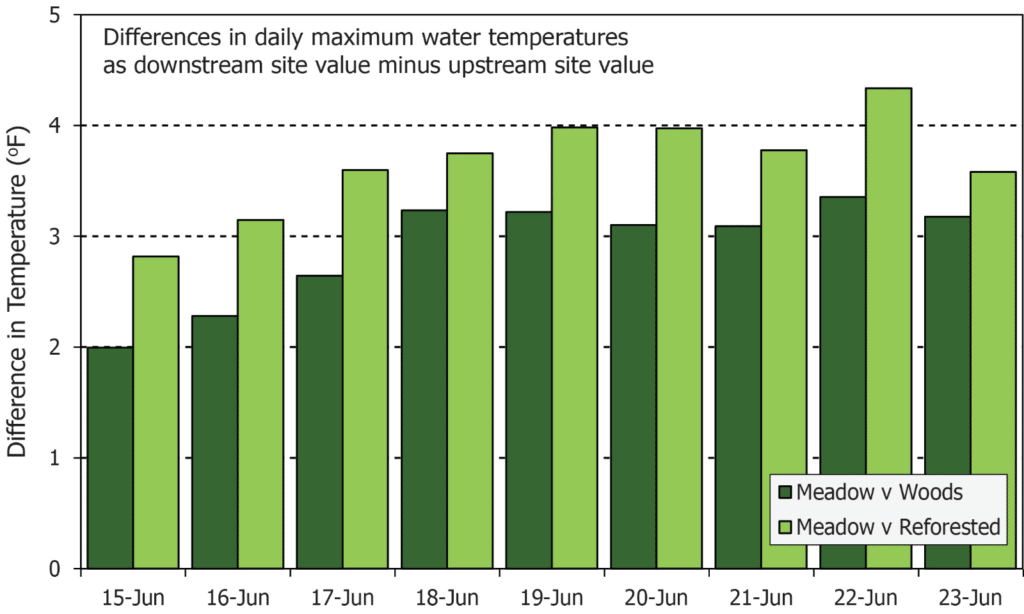

The last graph shows the temperature difference between the warm meadow location and each stream section protected by the forest canopy. The difference can be more than 4 degrees. In addition to the protection of the canopy, fallen trees and decaying leaves provide physical shelter and cooler pockets of water. Here, too, the forests help to provide critical support for stream life.

Consider the sensitivity of the brown trout. The fish feel the heat wave, too, but the forest canopy can provide some protection from extreme temperatures. The forested stretches don’t consistently move above the stressful 68 degrees Fahrenheit mark until late in the heat wave. Not so for the meadow reach, where the temperature crosses that threshold a day earlier and stays above 68 degrees for more extended periods each day.

The data also tells another story. Notice how closely the temperatures in both of the forested reaches track. The reforested canopy is doing one of its jobs, providing the same temperature-dampening benefit as the older forest.

The temperatures did drop somewhat after the heat wave. By June 25, the maximum water temperature in the meadow had fallen to 71 degrees Fahrenheit, giving respite to the inhabitants but still in the stressful range for brown trout.

Patience and Time Can Heal a Stream

This long-term reforestation experiment is still underway. Thirty-five years of study have shown us with patience and time, reforestation of our streams can provide the protection these systems need to survive and recover from generations of watershed use.

Without any mechanical intervention in the stream, such as sediment removal or engineered channel stabilization, the reforested reach of White Clay Creek resembles the old forested reach upstream. And that’s not just in temperature but in water chemistry, diversity of macroinvertebrate and fish populations, and the shape of the stream. In response to the streamside forest, this stretch of the creek has widened, creating habitat. It is shaded, keeping the water cool for trout and other species.

The Stroud Center continues to monitor the recovery of White Clay Creek and study the impact of reforestation on this and other streams around the world. We do this with your support. Your curiosity, willingness to learn, and concern for our streams and rivers keep us going. Thank you for being a part of this crucial mission!