This article is part one in a four-part series about riparian forested buffers in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. It is reprinted with permission from Lancaster Farming.

By Dick Wanner

If you’re a crow, you’re able to fly about 18 miles from Brilyn Acres to the mouth of the Conestoga River where it enters into the Susquehanna River, just below the Safe Harbor Dam in western Lancaster County.

If you’re a largemouth bass — a very determined largemouth bass — you’ll have to swim a good 50 or 60 miles to get to the Susquehanna via the Cocalico Creek, which flows through Brian and Lynette Sauder’s 90-acre farm just outside Akron in Lancaster County.

Three generations of Sauders and about 30 volunteers were on hand Saturday, April 10, for the final day of a three-day tree planting jamboree.

The purpose was to help ensure that the Chesapeake Bay — the ultimate destination of the Cocalico’s water — has a healthy future. About six-tenths of a mile of the Cocalico flows past the Sauders’ meadow.

Riparian Buffers

The volunteers were there to plant 700 trees that will grow to form a riparian buffer along the creek. Among other goals, riparian buffers are designed to stabilize stream banks; capture manure, fertilizer and sediment before they reach the water; and provide wildlife habitat.

Established and well-maintained buffers are also a recreational resource for activities like hunting, fishing and birdwatching.

With proper planning and the right selection of species, buffers can be harvested for nuts, fruits, berries and even timber. Buffers are considered one of the most effective and economical pathways to healthy streams and wetlands.

Farmers and other landowners are becoming increasingly aware of the economical environmental effectiveness of riparian buffers, according to Ryan Davis, project manager for the Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay.

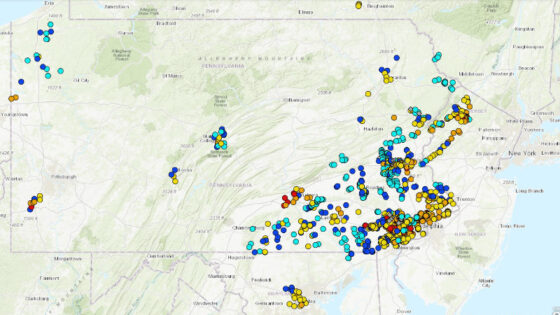

Davis works on forest conservation and restoration within the Pennsylvania, Maryland and New York parts of the Chesapeake watershed.

As part of his job, Davis was in charge of planning and designing the project on the Brilyn Acres farm. The process goes nowhere without the support of the landowner, he said.

“God blessed us with this land, and we want to do our little part in conserving it, preventing erosion, helping with the stormwater runoff, and just making it a better place for everyone,” Lynette Sauder said.

The Sauders became aware of the buffer program about two years ago when the Cocalico Creek Watershed Association received a grant from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation. The grant funded a land use survey of all the farmers in the Cocalico watershed. That survey was carried out by TeamAg Inc., just up the road from Brilyn Acres in the town of Ephrata.

John Williamson, an engineer with TeamAg and also a member of the watershed association, was one of Saturday’s tree-planting volunteers. He said the Brilyn Acres project, like many others, takes months of behind-the-scenes work before the first seedling goes into the ground.

The Sauders dedicated about 6 acres of land and significant labor to the buffer, but the funding came from a number of sources, including the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, the state Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, and Lancaster Clean Water Partners.

The work and the funds were coordinated by the Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay.

Buffers by the Numbers

Davis provided some particulars on the Brilyn Acres project.

- Cost: Around $6,500 for the trees. “I haven’t gotten the bills yet for two stream crossings and fencing to keep the cattle out of the buffer,” Davis said, “but I expect that to be about $36,000.”

- Funding source: Funds for the buffer, the fence and the stream crossings came from DCNR.

- Other assistance: There’s a buffer bonus right now that’s available through a DEP Growing Greener grant.

For every acre of riparian forest buffer that a landowner agrees to plant, the person gets $4,000 in vouchers for the adoption of additional conservation practices. That program is capped at $20,000 per landowner.

The Sauders plan to use the vouchers to pay for gutters and downspouts, feedlot cover and other improvements.

- Maintenance: The alliance will pay for the first three years of maintenance. Those are the most critical years for buffer establishment. That will cost about $6,500, which will be covered with grant money.

Beyond year three, there could be funds available from other sources, like Lancaster BEST — Buffer Establishment Support Team — a buffer maintenance fund coordinated by the Lancaster Clean Water Partners.

Otherwise, the landowners are pretty much in charge for the long term. They can do the maintenance themselves or hire it out. The alliance does follow-up to monitor the installation and to see if any additional assistance is needed.

“We do have an agreement with the landowner, which isn’t even a legal contract,” Davis said. “The Sauders signed our agreement to indicate that they will do their best, in partnership with the alliance, to establish and grow their forested buffer for a minimum of 25 years.”

Farm History

Brilyn Acres dates to 1943, when Brian’s grandparents bought it. His parents, Marvin and Betty Sauder, operated it as a dairy farm for many years before selling it to Brian and Lynette.

Their children, Brandon and Katelyn, are the fourth generation of Sauders to live on the farm.

The Sauders own land on both sides of the Cocalico. The south side is a steep, heavily wooded hill. The north bank includes about 60 tillable acres and 30 acres of floodplain.

The floodplain is flat and perfectly suited to pasture for their small Angus herd, which is key to sustaining their sales of Brilyn Acres-branded beef, pork and poultry.

The meats are processed at a nearby USDA-inspected plant, then delivered as frozen vacuum-packed cuts that are sold mostly at two local farmers markets. The Sauders also market through their website.