By Dr. James G. Blaine, Education Director

On the Way

It wasn’t a great start.

Before we had even finished unloading our 39 big black bags at Philadelphia airport early on the morning of August 14th, the cryo-shipper, a container used to keep field samples cold, tumbled from the van to the tarmac and discharged a suspicious white vapor.

Only three days earlier, London’s Heathrow Airport had been closed by a terrorist threat, and people were jumpy. As bystanders headed for cover, a police officer appeared with his hand on his holster. After a good deal of explaining and the removal of the liquid nitrogen remaining in the container, we were allowed to get in line.

We got to the counter, only to be told we were 15 bags over the limit and fined $100 for each. Most of the bags were filled with the scientific equipment that we — 12 scientists, technicians and educators from Stroud Water Research Center and a colleague from Florida State University — needed for our work in southeastern Peru. We planned to spend almost three weeks in the Amazon headwaters, studying the Madre de Dios River and its tributaries under a grant from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

The Amazon is the largest river system in the world and the source of 20% of all fresh water, and the rainforest to which we were headed is a cradle of biodiversity. We had two goals:

- To establish a baseline of scientific data on water quality, stream biodiversity, and stream health that would be a foundation for international conservation efforts.

- To create a series of education and monitoring programs for the people of the region.

A few minutes before 4:00 that afternoon our plane landed in Sarasota. Unfortunately, it was supposed to land in Miami but had been diverted by severe thunderstorms. Perhaps because we held 12 seats, American Airlines held our flight in Miami — a courtesy that unhappily did not extend to our bags. They arrived at Lima’s Jorge Chavez International Airport at 4:30 the next morning, and it was a tired, unkempt and hungry group that showed up to retrieve them. The first five of us made it through customs without incident, but the nonstop procession of black bags inevitably attracted official attention, and it took two hours and another $1,500 deposit to get cleared for our flight to Puerto Maldonado.

From the Andes to the Amazon

Flying southeast from Lima, we climbed up and over the steep and striated Andes, their brown slopes imprinted with occasional spots of copper, yellow and green that reflected the morning light. We passed over treeless mountain lakes and across a broad plateau pocketed with small, dusty glaciers and streams dropping into narrow river valleys. Occasionally the flat metal roofs of isolated villages sparkled like rhinestones, but mostly we looked down on a bleak landscape broken only by the empty roads that wound through the mountains. Few civilizations built roads like the Incas, who, on the eve of the Spanish invasion, had a 10,000-mile network of roads and bridges that connected an immense empire stretching from present-day Colombia to Patagonia. While the vast Amazon system begins in these mountains and flows eastward to the Atlantic, the Incan empire was never able to penetrate the rainforest nor subdue its inhabitants. After a short stop in Cuzco, we took off on our final leg to Puerto Maldonado, ascending over small brown fields and pastures cut into steep slopes, past distant glacial peaks, to a land of dense forests and meandering red-brown rivers. “Flying into this rough-and-ready frontier town,” wrote Conservation International’s Mike Satchell, “the endless unbroken expanse of brilliant green rainforest suddenly opens into a vast ocher wasteland. From 20,000 feet, this barren and bizarre panorama resembles a Martian landscape — or a vision of wanton destruction, which is exactly what it is. The giant scar across the earth is 25,000 mercury-poisoned acres of red, orange, brown, yellow, and gray sediments and tailing wastes along Huaypetue, a tributary of the Inambari River. It is the legacy of indiscriminate, unregulated gold dredging by some 15,000 miners on land owned mainly by the powerless and vulnerable Amarakaire Indians.” The mercury, which is used to separate the gold from the dross, has poisoned the rivers as well. As we stepped off the plane, the heat hit us like a blow dryer. We collected our bags, piled onto a bus and drove to the river port through dusty streets filled with motorbikes and scrawny dogs. Located just above the confluence of the Madre de Dios and Tambopata rivers, Puerto Maldonado is a city of 80,000 people, the capital of a region characterized by gold mining, land-development plans and exploding population growth. It also lies within perhaps the world’s largest remaining expanse of virgin rainforest. The greatest threat to that forest comes not only from the gold mines but also from the planned construction of a macadam highway that will eventually connect the Brazilian interior to the Pacific coast and the lucrative Asian markets beyond. While much of the discussion around the new road focuses on transportation and commercial issues, it is above all a real estate deal, and land speculation is rampant in the region.

On the River

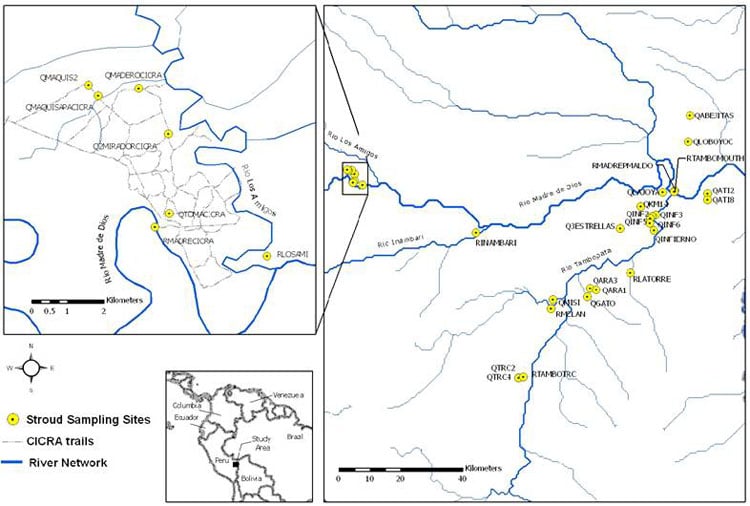

The area has few roads beyond the limits of Puerto Maldonado, and rivers remain the principal transportation arteries. We traveled in long canoes with outboard motors, sometimes for hours at a time. Our boats passed mounds of dirt and stone that resembled huge anthills along the banks — the collective product of thousands of small prospectors chasing the big chance and the gold that washes down from the Andes. We watched men, standing waist-deep in water, bore gashes into the stream banks with high-pressure hoses, the noise of their equipment drowning out all other sounds. We saw few signs of wildlife anywhere. Throughout history, people have used rivers as public commons to be exploited for their many benefits. Civilizations grew on the banks of great rivers, which provided food and irrigation, drinking water and sanitation, transportation and power. Here on the Madre de Dios, we were witnessing the tragedy of those commons, as gold miners, who reportedly hold concessions on every square meter of the river, ravaged a priceless public asset for purely private gain. On those stretches through forest preserves where mining is forbidden, we found ourselves in the midst of remarkable beauty. At times the river was as still as an Eakins painting, with wide sandy beaches undulating out from bends in the shore . . . a family of capybaras playing near the water, ambling away as we draw near . . . cormorants perched on dead trees in the middle of the river . . . an osprey circling effortlessly above us. Over the years Stroud research has demonstrated the connection between population growth and deforestation on one hand and the degradation of streams and rivers on the other. Particularly vulnerable are the small and medium-sized streams that are often overlooked in public debates about fresh water, but which provide more than 90% of the overall water supply. Protecting them is vital, and doing so requires us to look on our streams and rivers not simply as systems to deliver goods and services but as ecosystems. During our time in the region, the Stroud team sampled 31 stream and river sites that ranged from pristine to severely polluted. We employed a variety of physical, chemical and biological parameters to assess the health of the streams, gauge the impact of human activities on water quality, create a baseline of conditions against which to measure future changes and establish a set of protocols that will enable people in the region to monitor stream health.

In the Rainforest

We began our work a few miles downstream from Puerto Maldonado at a facility operated by the Amazon Center for Environmental Education and Research (ACEER), whose U.S. offices are at West Chester University. It is in the Vilcabamba-Amboro Forest Ecosystem region, which contains over 4 million acres of protected primary forest and was a refuge for plants and animals during the last ice age. The region includes some of the oldest rainforests on Earth and is, according to ACEER, “the epicenter of biodiversity on the planet.” Several years ago, in fact, E. O. Wilson identified 362 species of ants at Reserva Amazónica just across the river, the most ever found in one place. August is dry season in the rainforest, and the footpaths are filled with fallen leaves of varying shades of tan, brown and muted greens. Although the foliage is lush, long-leaved and green, the forest is hardly a riot of colors. There is an occasional red flower, and sometimes a bird of paradise appears, almost as an epiphany. Because the plants quickly take up the organic matter that falls to the ground, the soil’s nutrient content is low, and beneath the surface there is little but sand. When the trees are cut down, the forest does not grow back. Today, the Amazonian rainforest is losing about 4% of its area each year. Human activities on the land have a direct and significant impact on conditions in the streams and rivers. The key to protecting clean water is to preserve the rainforest, particularly in headwaters areas and along stream corridors. Conversely, the key to protecting the forest is to safeguard the streams that run through it and provide the water essential for forest life.

In the Field

Early one morning we set out for Quebrada Abejitas, a stream that runs through cattle country across the Madre de Dios River from Puerto Maldonado. After taking a ferry across the river, we hired a Toyota Corolla and a Toyota Corona, two dilapidated taxis covered with dust and sporting spider-webbed windshields and bald tires. As we careened down the red dirt highway, we quickly learned to roll up the left windows when a car approached. Other than that, we just hung on for dear life. In an age in which molecular studies in the laboratory have largely replaced natural research in the wild, the Stroud expedition had one foot firmly planted in each world. Out here, fieldwork becomes an absorbing combination of modern scientific precision and old-fashioned trial and error, subject to the vicissitudes of nature and the vagaries of man. It is research that requires more than scientific knowledge and laboratory techniques. It also demands adaptability and ingenuity. Unpredictable things happen — rainstorms in the dry season, equipment breakdowns in remote places, people falling into the stream. The exactitude of the scientific method must yield at times to unforeseen events. It also takes endurance and courage for these scientists to follow a stream wherever it flows and their research wherever it leads. Driven by their quest for data, they walk for miles in wilting heat, lug bulky equipment along root-infested paths, and return with welts the size of quarters. One afternoon, we hiked two miles to a remote stream, only to find no way down to the site. Jan Surma went scouting for a route, and suddenly he was yelping and running and frantically flapping his hat, desperately trying to escape the wasps into whose nest he’d stumbled. Inevitably, something goes wrong.

“This is why we went to elementary school,” says Denis Newbold, doing long division on a scrap of paper because his calculator was destroyed in the morning rain.

“Nothing is simple around here,” says Tom Bott, as he sits for six hours by a stream, taking periodic metabolism measurements, fending off mosquitoes and the tropical heat.

“You have to be MacGyver,” says Dave Montgomery as he tries to fix a broken centrifuge. “Troubleshooting is a big part of our job.”

Going Home

At 5:30 in the morning of our last day, we had to round up the frozen samples that had been spread throughout a town with little refrigeration. The ones in our hotel restaurant’s ice cream freezer did not freeze. Some of those we had left at a local agency had been removed to make room for slabs of meat. Others had been taken to somebody’s house — to which Bern Sweeney and Mike Gentile sped in a motorbike taxi, pooling their money to retrieve the goods. All these bottled samples only added to the customs drama that night at Lima airport. But after three hours, we managed to clear customs and board our flight for Miami. We took off a few minutes before midnight and touched down in Philadelphia just over 12 hours later. The trip was over, but the work had only begun. Coming on the heels of the 4th World Water Forum in Mexico City in March 2006, which “reaffirm[ed] the critical importance of water, in particular fresh water, for all aspects of . . . sustainable development and poverty reduction strategies,” our work in Peru is part of a global effort to protect one of the world’s most critical resources in one of the world’s most vulnerable environments.

Post Script: Fall Workshops

In October scientific and education staff members returned to Madre de Dios to give a series of full-day workshops on water-quality monitoring and the ecology of streams and rivers to: (1) local public- and private-sector decision makers; (2) teachers; (3) conservation planners and (4) eco-tourism guides. We targeted our efforts both at those now in positions to make decisions about water resources and at those whose students will become the stewards of the future. In December the Stroud team gave a similar series of workshops in Costa Rica.

Presented in Spanish and offered free of charge, the workshops introduced the participants to freshwater ecosystems, taught simple and affordable methods for monitoring streams, and encouraged best conservation practices. Each workshop began with information about local and global water issues, the relationship of land use to stream health, the impact of human activities on water quality, and the critical interplay between streams and forests.

Workshop participants then walked to a nearby stream where they made chemical measurements of water quality and collected aquatic macroinvertebrates. Later they spent a couple of hours in the laboratory sorting and identifying the animals they had collected and learning about the role they play as indicators of stream health.

Perhaps the most consistent message that came through in the workshop evaluations was “we want more” — more information, more time to learn, more and better tools to make a difference, more workshops for more people. A corresponding message was “we want it now” … because at the rate the region is changing, there is no time to lose.