Although Joseph George spent much of his childhood in a quiet suburb of Nashville running through woods, climbing trees, and splashing through the small stream that ran near his house with his brother and friends, it wasn’t until his teenage years, when his family began taking regular trips to Great Smoky Mountains National Park, that he became seriously interested in the outdoors and natural science.

He “fell in love” with geology during his second semester at Middle Tennessee State University, and by the middle of undergrad, he was taking a two-week summer field course studying the physical and cultural geography of Appalachia. The course included a day in West Virginia working with a watershed restoration group to monitor streams for signs of acid mine drainage contamination. Joey George volunteered to take discharge measurements that day while other students collected measurements of water quality.

“While I fought to stay upright in those cold, waist-deep, fast-moving streams, I began to see the bigger picture of the role streams play in the natural world. I no longer saw streams as just places to cool off with friends on a hot day; I started to see them as conduits that transport water, sediment, nutrients, organisms, and sometimes contaminants and that support a wide range of ecosystem functions. I think I decided that day to make a living in and around streams,” he recalls.

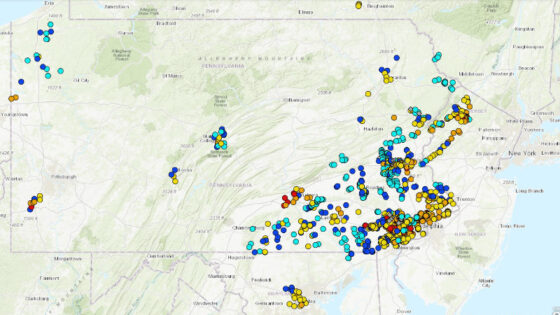

George went on to pursue a master’s degree in fluvial geomorphology at the University of Delaware, where he focused his research on determining how much fine sediment is stored in the gravel bars and floodplains of Mid-Atlantic streams and for how long. His research was part of a larger effort to understand the effects of best management practices aimed at reducing sediment pollution that reaches the Chesapeake Bay from upland farms.

After completing his master’s degree, he spent three months working with scientists in Mount Rainier National Park to better understand the geologic hazards in the park and how to mitigate the threats those hazards posed to visitors and park infrastructure. He followed that with a data processing position as part of Northern Arizona University’s Grand Canyon Sediment Survey and a teaching assistantship at the University of Missouri Geology Field Camp, in Lander, Wyoming.

By the spring of 2018, his former adviser, Jim Pizzuto, from the University of Delaware contacted him with an interesting job prospect. Stroud Water Research Center was looking for a new staff scientist to work in the Fluvial Geomorphology Group, assisting with a six-year project funded by The William Penn Foundation to improve soil health and water quality in collaboration with Rodale Institute.

“I was struck by the culture of Stroud and their history of progressive research,” George recalls. He joined the Stroud Center in August. “My experience at Stroud so far has been a very welcoming one. Everyone I have interacted with has been kind, helpful, and genuinely interested in me and my experiences. I’m very excited to be a part of a group of scientists and educators that all have a similar goal: to further people’s understanding of freshwater ecosystems and to improve these systems through research, education, and restoration.”

George is also looking forward to learning more about agriculture and different farming practices. “I’m excited by the prospect of interacting with farmers and learning to take their concerns into consideration when planning and implementing tasks related to this project. I come from a family of farmers (although a generation or two removed), so I guess I’m interested in getting a better idea of what their experience was like.”