This article is part of a four-part series about riparian forested buffers in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. It is reprinted with permission from Lancaster Farming.

Text and photos by Dick Wanner

In the year 2000, Roger Rohrer planted 750 trees on five acres of pastureland that has been in his family since 1893. It was one of the earliest attempts to establish a riparian buffer in Lancaster County.

Rohrer wasn’t sure how long the five acres had been pastured. His educated guess was that it had been cleared in the early 1700s, about the time Marie Ferree and her family fled religious persecution in their native France.

They settled in Strasburg Township, founded a village called Paradise and introduced animal agriculture — and pastures — to their corner of Penn’s Woods.

“There’s nothing wrong with pasture,” Rohrer said in a break between bouncing around his 200 acres in a red Polaris Ranger. “But pasture with animals in a stream? That’s a problem.”

It’s not just a manure and urine problem; it’s also a stream bank destruction and sedimentation problem.

We visited Rohrer in the company of Teddi Stark, who is the watershed forestry program manager for the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources.

It was Stark’s first visit to the farm, where she saw the Rohrer family’s embrace of riparian buffers and other conservation best management practices.

A Rough Start

The first spot Rohrer took us to was that five acres where he’d planted 750 trees in 2000 as part of USDA’s Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program.

The program had a list of allowable tree and shrub species, all of which had to be Pennsylvania natives, a rule that still holds.

Rohrer’s trees are mostly deciduous — swamp white oak, red oak, tulip poplar. He got an OK to include a few conifers, like white spruce and white pine.

In 2000, the trees had to be planted at random, rather than in rows, and Rohrer couldn’t spray for weeds or mow between the trees.

Without mowing or spraying herbicides around the tree seedlings — standard practice today — for the first three to five years, the buffer plants were a haven for unwanted species.

Voles flourished in the ground cover, and they stripped the bark from the young trees. Without spraying to keep invasives in check, species like Canada thistle and mile-a-minute vines could shoulder out the natives. Tree mortality in that first buffer was very high.

The rationale for letting nature take its course was that a buffer should look natural. So nature, unmolested, did what it wanted to do with the Rohrer farm’s first buffer.

And what nature apparently wanted to do was to kill every one of those 750 trees. Which it almost did. In the first five years, nearly every tree had to be replanted at least once.

Making Progress

Did the experience turn Rohrer against riparian buffers? Did he come to believe they were a lost cause?

Not at all.

“I can’t criticize anybody,” he said. “We all had this idea of what a buffer should be. It should look like a native forest with native species growing willy-nilly. For those early buffers, there was no support for maintenance after the installation. We were all learning together. We have learned. We know better.”

What they all learned — the landowners, the funders, the regulators — was that the first three to five years of a buffer’s existence are the most critical. A plant-it-and-forget-it approach guaranteed failure.

After enough of those failures, the notion caught on that buffers need maintenance, which is another word for management.

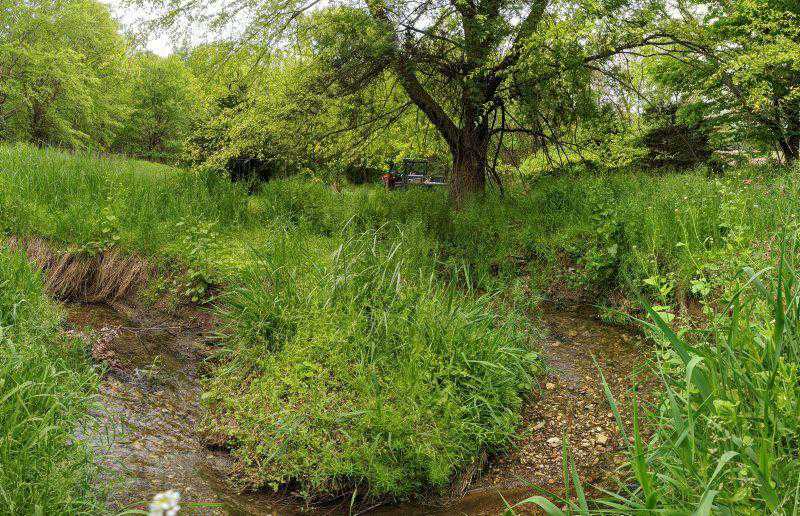

Today, with diligent replanting and weed management, the first buffer is mature, has a developed canopy and doesn’t get mowed.

Frankly, it doesn’t look like much. A patch of ground with a tulip poplar here, a black willow there and a hackberry bush yonder.

There’s a grassy patch that’s home to wild turkeys. Deer roam the buffer, the entire farm, in fact. Rohrer and his sons, Todd and Mark, have amassed what for most hunters would be a lifetime’s worth of trophy whitetail racks.

Curling through that patch of wilderness is a shallow stream, maybe a yard wide. At one time, the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection carried the stream on its statewide list of impaired bodies of water.

It didn’t have a name, but it was on the impaired map — until it and two other Lancaster County streams were taken off the list in 2019.

Delisting is a thorough, tedious process involving lab tests for water quality, and people with advanced degrees mucking about in a stream, turning over rocks and looking for the kinds of aquatic life that can only exist in pristine water.

When there’s enough evidence to conclude that a stream should be delisted, there’s a ton of paperwork.

The Rohrer farm has won all kinds of conservation awards from the state and the county, but the honor Rohrer seems to treasure the most is the simple delisting of a no-name stream that trickles through his 20-year-old buffer.

“Did the buffer help clean up this stream?” Rohrer asked, standing on its bank. “Probably. Did 20 years of no-till help clean it up? Probably. Did 10 years of cover crops help? Probably. And the fact that the headwaters are only a mile away definitely helped.”

Rohrer said that there came a point in time when, having spent his entire life on his family’s ancestral farm, and having witnessed how easily the soil was moved by storms, he needed to do everything he could to keep the soil on the farm and out of the stream.

Over the past two decades, he has guided the installation of diversion terraces, grass waterways, drain tiles and covered manure storage.

Rohrer stressed that it’s not just one practice that can clean up a stream, but a lot of practices. And it’s not just one farmer; it takes every farmer along a stream to get it clean and keep it clean.

Rohrer said he’s working on his neighbors, in a friendly kind of way, to convince them to clean up the water downstream from his place. That part of the stream, which flows into Beaver Creek, which flows into the Pequea, which flows into the Susquehanna, which flows into the Chesapeake Bay, is still impaired.

Seeing Improvements

Rohrer and his sons work the farm together. Their primary enterprise is raising nearly a million organic broilers a year for Coleman Natural Foods. They grow corn, soybeans, wheat and 6 acres of Pennsylvania type 41 tobacco.

They save fertilizer expense by spreading poultry litter on their fields in accordance with their manure management plan.

In 2010, the Rohrers installed their second riparian buffer, 600 trees on 4.5 acres. They planted that buffer not in spite of the experience with the first buffer, but because of what they learned in the process.

The second buffer trees were planted in rows for ease of mowing. Sprays were used around the tree tubes to reduce vole hiding spots and to keep invasives in check.

Rohrer estimated tree mortality in the second buffer at 30 to 40%, and all the dead ones were replanted. The replanting costs were paid for jointly by CREP and the Rohrers. CREP provides a small amount of money every year for buffer maintenance.

A third buffer, 200 trees on 1.5 acres, was planted in 2016. Rohrer estimated tree mortality at 5%. The trees were planted in rows 14 feet apart to accommodate the farm’s 10-foot rotary mower. Sprays and tree tubes have kept vole damage to a minimum.

A few of the young trees have been lost to buck rubbing, but if you live with whitetails, which the Rohrers are happy to do, you’ll have some of that.

Just up a hill from the third buffer is a 4-acre field that’s planted to switchgrass, a warm-season grass that can reach 6 feet in height, with roots that can go down another 6 feet.

The Rohrers are in the fifth year of a 15-year contract to keep the steeply sloped, highly erodible field in switchgrass.

It can’t be harvested, but it can be mowed during the establishment period. There are several switchgrass plots on the farm’s steepest slopes.

Payment rates for CREP contracts are based partly on soil types. Lancaster County has some of the highest quality soils in the U.S., so payments to county cooperators tend to be higher than they are in other parts of the state and the country.

A Lancaster County farmer who signs a 10- or 15-year contract for a permanent stand of warm-season grass, like switchgrass, in excellent soil on a steep slope could be looking at an annual payment of $400 or more per acre.

On the Rohrer farm, the field downhill from the switchgrass is planted to a variety of row crops. Over a five-year period, Rohrer expects to average $800 in gross receipts per acre.

Out of that $800 he has to pay for seed, fertilizer, pesticides, fuel and labor for planting and harvesting, and transportation costs for getting the crop to the mill.

In a normal year, gross minus expenses leaves a net of $200 or $300 per acre, Rohrer said.

If that acre would be on one of his steeper slopes, the environmental and management challenges, and probably lower yields, would cut into the net.

The Rohrers have 20 acres of their steepest slopes in switchgrass, mostly for environmental stewardship, but also for the CREP payments.

The 2020 cost for the switchgrass acres? Zero. Zip. Nada. The Rohrers only have to watch it grow and cash the CREP check.

“Why aren’t more of my neighbors planting switchgrass on their steeper slopes?” Rohrer asked.

In addition to the switchgrass, the farm has 12 acres enrolled in the CREP riparian buffer program.

The CREP payments don’t add up to another enterprise for the farm, but they do give a modest boost on the bottom line.

The real payoff for the Rohrer family is the environmental stewardship on 200 acres that have been permanently preserved through the state farm preservation program and the Lancaster Farmland Trust.

Preservation proponents are given to saying that “preservation” means “forever and a day.” So what Roger Rohrer’s ancestors began in 1893 may look different in another 127 years, but it will still be a farm.

And maybe not look so different.

Getting Started With CREP

Ashley Spotts, a restoration specialist with the Pennsylvania office of the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, has been working with Roger Rohrer for about 15 years.

She is an expert on the ins and outs — of which there are many — of USDA’s Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program.

Rohrer has been enrolled in CREP programs since 2000, when he installed a 5-acre buffer on his farm in Strasburg Township, Lancaster County.

Rohrer knows that CREP can pay for the installation and maintenance of conservation practices on his farm — like riparian buffers and warm-season grass wildlife habitat — but still checks in with Spotts and other conservationists about new programs and changes to existing programs.

Farmers just getting started with conservation practices can look to several places for guidance. Spotts suggested these:

- County offices of the USDA Farm Service Agency, which administers CREP.

- County offices of the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. NRCS can assist with CREP and the Environmental Quality Incentives Program, which helps farms put in grass waterways, terraces and manure storage.

- State and national clean-water groups. These include the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay, National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and National Audubon Society.

- Local clean-water groups that provide money and volunteers to establish conservation practices. In Lancaster County they include the Lancaster Farmland Trust and Lancaster Clean Water Partners.

But it doesn’t really matter where you start, Spotts said, because conservation groups are good at cooperating.

“We all have a good idea of what every organization is doing,” she said, “and if whoever you call doesn’t have the answer to your questions, they’ll have a good idea who to call to get the answer.”