Ruth Patrick, Ph.D., a pioneer in environmental science and aquatic ecology and the woman who first conceived of the idea for Stroud Water Research Center, died September 23, 2013, at 105 years old.

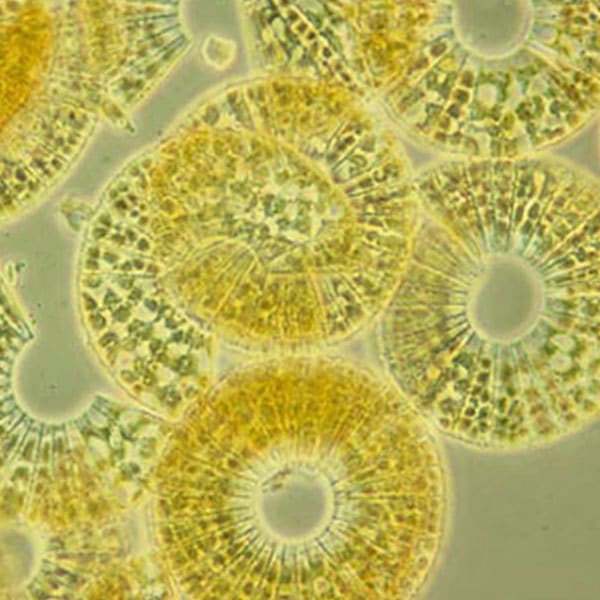

Her outstanding career in limnology, which focused on the study of streams, spanned eight decades and earned her worldwide recognition, most notably for her work on diatoms, a type of algae.

She worked for the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, where she held the Francis Boyer Chair of Limnology, for more than 70 years. Officially, she retired three times, but her work continued. At 100, she remained a trusted authority on environmental issues among industry CEOs and United States presidents.

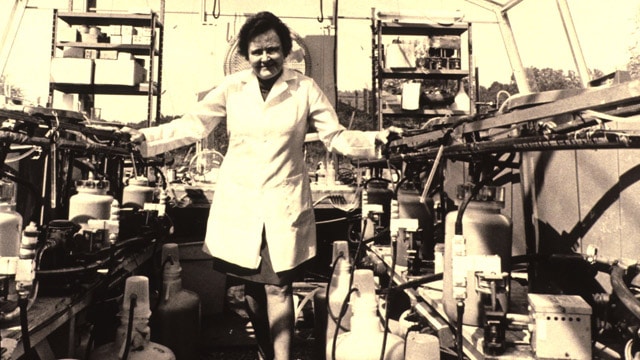

She reached the top of her field, and she did it during a time when women scientists were rare. “I think she saw it as a challenge,” says Sherman Roberts, a researcher who joined the Stroud Center’s staff in 1972. “She wasn’t going to let her gender stand in the way.”

Driven by her passion for science, her unquenchable thirst for learning, and her desire to make the world a better place, Patrick blazed many new trails. The best model that scientists have today for evaluating water quality in streams and rivers involves looking at biological diversity. The Patrick Principle, as the model is now called, was her idea.

She also helped draft what became the central piece of legislation to protect streams and rivers throughout the U.S. from degradation — the Clean Water Act.

A Novel, Multidisciplinary Approach

As the first person to lead a broad survey of stream pollution in North America, she brought national attention to Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. In 1948 she and a carefully selected team of scientists set out for the Conestoga River to study its physical, chemical, and biological characteristics. Such a multidisciplinary approach to science was equally novel; that’s how she worked because she understood the value of collaborative science, a precedent she also set for the Stroud Center. Our scientists and research staff follow her example to this day.

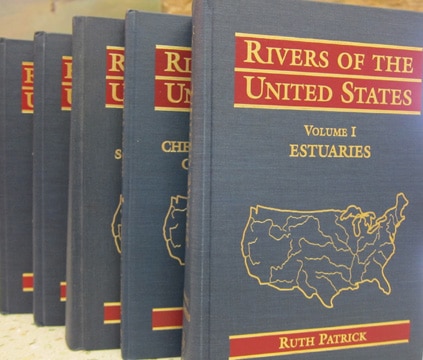

Over the course of her career, she wrote some 200 scientific publications and several books and received numerous honors and awards, including the National Medal of Science in 1996 from President Clinton.

Believing that science could be used to affect positive changes in the natural environment, Patrick intentionally nurtured relationships with CEOs and other influencers in industry to work toward best management practices and pollution reduction. There were many who were eager to seek her counsel on such matters, and so she created the Environmental Associates, a group of corporate executives concerned about environmental effects of industrial activities.

Stroud Center Director Bern Sweeney commented, “Ruth believed in studying both natural and degraded systems.” He recalled that Patrick used to tell her students, “‘If you have the opportunity to put your head between the banks of a polluted stream, do it, because you will learn something.’”

She said it added perspective to the science. Furthermore, she thought by working with companies, she could help them. “If Ruth was that convinced companies were sincerely committed to reducing their environmental footprint, she wanted to advise them.”

A Mentor to Scores of Scientists

Equally committed to mentoring students and young scientists, she made available to them her impressive network of connections, frequently inviting leading scientists from around the world — Evelyn Hutchinson, Francisco Aayla, E. O. Wilson, Arthur Hasler, George Woodwell, Luna Leopold, and Robert May — to her classroom and the Center. “When she would come to the Center for her own research, she often made a point of asking us, ‘What did you learn this week?’” said Sweeney.

She was bright, savvy, and intensely likeable. Whether it was in the lab or the field, the boardroom or the social scene, she was always comfortable, always gracious, and always full of energy. She commanded respect and demanded hard work and excellence that matched her own.

Tom Bott, research scientist emeritus, who came to the Stroud Center in 1969, said, “She liked being at the nexus of academia, industry, and government because she could share her knowledge and experience to help solve complex problems. I think Ruth will be remembered certainly for her work but also for her desire to help people.”