Narrower Buffers Help But Don’t Deliver All Needed Benefits

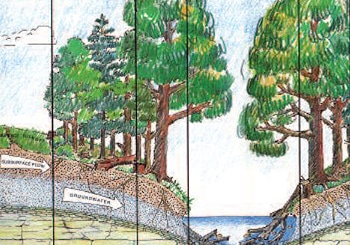

For decades, strips of forest along stream channels have been used to filter contaminants from agriculture and other land uses, keeping pollutants out of streams.

The benefits of these riparian buffers are many, but this particular benefit — reduction of contaminants entering streams — has long dominated social and policy conversations.

Stroud Water Research Center has demonstrated that riparian forest buffers play another important role: improving the health of the stream itself. Healthy streams provide more and better ecosystem services for humans and wildlife, and they process natural organic matter and pollutants more effectively than unhealthy streams.

Forest buffers improve stream health in two significant ways. First, they keep sediments and nutrients out. Second, they keep sediment and nutrients from moving downstream, maintaining clean water in our streams and rivers.

Good News, Bad News

The Stroud Center published a case study showing that creating a forest buffer showing can keep on average 43% of sediment and 27% of nitrogen from entering a stream. This is good news. The bad news is that a majority of the sediment and nitrogen still penetrate the barrier.

Fortunately, forested buffers can also help address the fraction of pollution that does reach the stream. A Stroud Center study showed that a forested stream section reduces two to eight times more nitrogen than an unforested section of the same stream.

It’s important to look at forest buffers both as a pollutant barrier and as an enhancer of in-stream function when considering how they improve waterways.

When we consider both of these benefits, it’s clear that a forest buffer provides better protection and more bang for the buck than a buffer filled with grass.

Creating a More Functional Ecosystem

Trees along streambanks prevent erosion, keep stream channels wide, moderate water temperature via shading, and promote increased amounts and diversity of food in the form of leaves, algae, and dissolved substances.

The Stroud Center has long advocated for forest buffers. Staff scientists began publishing studies on forest buffers in the 1970s. Experimental tree plantings began as early as 1982.

Of course, it makes sense that wider buffers would work better than narrower ones, but exactly how wide was debated until Stroud Center scientists Bern Sweeney, Ph.D., and Denis Newbold, Ph.D., conducted an extensive review of scientific literature on the topic of forest buffer width.

RESULT: Forest buffers should be at least 30 meters, or nearly 100 feet, wide on both sides of a stream to adequately protect it.

Science to Practice

The Stroud Center’s Robin L. Vannote Watershed Restoration Program customizes riparian buffer plans for farmers and landowners. Practical constraints of farming needs, near-stream infrastructure, or property line setback can limit buffer width. Projects the Stroud Center supports must provide a minimum of 35 feet for a new buffer. This buffer width will include at least two to three rows of native trees and shrubs on each side of the stream.

While narrower buffers do not provide the entire suite of benefits described in the literature review, they support the stream ecosystem with shade, extensive root penetration throughout riparian soils, and carbon inputs. In recent years, the restoration program’s average buffer width in Lancaster County was 57 feet per side. In Chester County, the average has been at or near 100 feet per side, the gold standard that Sweeney and Newbold identified.

- Learn more: Read the full case study at bit.ly/100ftbuffers.

- Join us: To receive our freshwater science, education, and restoration e-news, sign up at stroudcenter.org/subscribe.