Message from the Director

“Q Words” of Life and Science

“Quality” versus “Quantity?” How often do we engage in that debate in our daily lives? Is more better? Is small beautiful? Would you rather be a jack of many trades or a master of one? Dine annually at Le Bec Fin or weekly at the local diner?

In our work on streams, rivers, and their watersheds, we face such questions all the time. Do we need cleaner water or more water? Which is better, natural or regulated flow? Do we want better fishing or more sewage treatment plants?

Nowhere is the quality-versus-quantity debate livelier — or tougher — than in our conversations about what kind of place we want Stroud Water Research Center to be. It permeates our staffing issues: Will our resources go further if we hire one great scientist or two good ones? Should we focus on one stream over a long time or study a variety of streams less intensively? Should our education programs seek to influence relatively few people in-depth or spread our resources more broadly — and so more superficially? Should our scientists spend their time polishing one painstaking monograph or several more cursory papers? These are not simple questions, and they have become a lot more difficult of late as both our clients and our funding agencies now demand more output — with higher quality assurance — for less money.

While we believe in the need to produce as much good science as we can, we draw a firm line on the side of quality. We believe our thirst for a new understanding of streams and rivers will best be quenched with fewer but better staff, fewer but better projects, and fewer but better publications. We will grow—but never at the expense of quality.

And what does making quality the “Q” word of choice at the Stroud Center mean? It means we can’t be all things to all people. It means we must know who we are and what we do. It means following our research wherever it leads. It means no easy answers. It means we firmly believe in better science and better education.

Bern Sweeney

Director

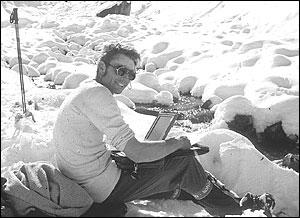

A Quick Tour of Costa Rica

Sampling the Tropics with Camera Crew in Tow

Sampling the Tropics with Camera Crew in Tow

Director Bern Sweeney spent a whirlwind five days in Costa Rica early this spring, filming, sampling, and touring the Stroud Center’s facility in the country’s mountains. With him were Silverwood Films’ director Richard Robinson and cameraman Jeffrey Confer, who are making a video for the Stroud Center. (See “On Film” below.)

A highlight of the Costa Rican trip was the filming of an interview with noted University of Pennsylvania ecologist Dan Janzen, who is involved in several research projects in the Área de Conservación Guanacaste near the Río Tempisque. The crew also filmed the Stroud Center’s lab and its two Costa Rican staff members.

While he was there, Sweeney delivered samples and returned data for a National Science Foundation project on the Río Tempesquito being conducted by Stroud Center’s Senior Research Scientist Lou Kaplan. He also took samples for a project he is doing with Research Scientist John Jackson on assessing rising levels of pollution in tropical stream macroinvertebrate communities.

Finally, Sweeney also continued negotiations on the Stroud Center’s operating contracts with the Costa Rican government and nongovernmental organizations.

ON FILM

Silverwood Films is making a video recording of the story of the Stroud Center.

The film, made possible by a generous grant from Marion “Kippy” Stroud, will be a 10-minute presentation of the Stroud Center’s work and history. It is similar in content to “A Portrait: 1967-2000,” a publication available at the Stroud Center.

The production will include interview snippets with Stroud Center co-founders W.B. Dixon Stroud Sr. and Dr. Ruth Patrick, former director Robin Vannote, and current director Bern Sweeney. Hudson Riverkeeper Counsel Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who opened the Stroud Center’s new streamhouse last year, will also be interviewed for the film.

National Science Foundation Report Backs Woodland Restoration

Stroud Center’s scientists have completed a comprehensive analysis and comparison of 16 paired woodland and meadowland streams that strongly support the restoration of streamside forests. The study streams are Buck Run, Doe Run, Buck and Doe Run, East Branch White Clay Creek, Middle Branch White Clay Creek, West Branch White Clay Creek, Big Elk Creek, and Pocopson Creek.

The study—spearheaded by the Stroud Center with the collaboration of Penn State University, the University of Delaware, and the Academy of Natural Sciences—is documented in a 46-page report plus tables and charts for the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

The results show that woodland buffers make streams wider and shallower than their meadow equivalents. They further show that the extra width enhances the stream’s biological systems that keep the water clean by digesting nutrients and other potential pollutants.

As the report analysis puts it, “It now has been shown in this study that increasing the amount of benthic area (habitat) per unit channel length via streamside reforestation can greatly enhance overall stream ecosystem activity (i.e., biological community structure and biomass, bio-geochemical function, etc.).”

In addition to the detailed study of the streams, the landowners were interviewed and surveyed to assess their attitudes and land-use practices.

The ultimate goal, according to the report, was to bring both the natural and social science components into focus for policymakers and regulatory agencies.

Prepping for New York Project Year Two

After a hectic winter of lab work, the Stroud Center is gearing up to begin the fieldwork for Year Two of the three-year study of the 2,000-square-mile watersheds that provide New York City’s drinking water.

Several field workers have already braved the icy waters of the upstate New York streams to do some winter sampling. In February and March, fighting ice and sub-zero winter chill factors, Arlene Casas and Jessie Mathisen sampled stream sites east and west of the Hudson River and in the upper Delaware River.

Back at the Stroud Center, the labs were busy throughout the winter processing the thousands of samples of water, algae, and macroinvertebrates taken from the streams and reservoirs last summer. In January, several oral and slide presentations were made to the sponsoring New York and federal agencies, and a 200-page progress report was delivered in early March.

“The bottom line on New York,” said Stroud director Bern Sweeney, “is that we have completed all the sampling and sample processing for all the project elements. We are heavily into the data analysis stage for the first year’s data.”

He was speaking in the first week of March. By the time UpStream comes off the press, the final report will have been completed and delivered to New York.

Sweeney explained that the same sampling and measurements would have to be repeated for another two seasons.

“From our work in the past,” he said, “we have found that we really need to study each site for at least three years to make sure they are not confounded by something unusual that happened, like a major storm. We don’t want to rush to judgment.”

He noted that no matter how well the scientists design a research program at their desks, there are always surprises in the field — particularly in the first year of a new project.

The 60 carefully selected sampling sites are spread over a 2,000-square-mile area in rugged terrain in two major watersheds — the Hudson (east and west) and upper Delaware.

“We’re looking forward to a more efficient and effective second year — but that is not to say we were disappointed in the first year,” said Sweeney.

The New York project involves all the Stroud Center’s 40-plus staff members, from scientists and technicians to administrators.

Stream Studies for National Science Foundation May Shed Light on Global Warming

What can studying the metabolism of bacteria that inhabit nine streams in the New Jersey Pine Barrens, Chester County’s rolling hills, and the mountains of Costa Rica tell us about global warming?

Right now, nobody knows for sure, but the Stroud Center’s Senior Research Scientist Lou Kaplan thinks that one day, the answer could be “Plenty.”

In search of the answer to that and other questions, Kaplan assembled an interdisciplinary team of scientists from across the country to study the structure of organic molecules and the species composition of bacteria in streams. They are now at about the halfway point of a three-year, $1.4-million grant from the National Science Foundation.

Using a variety of cutting-edge techniques, Kaplan, Patrick Hatcher of Ohio State University, David Stahl of the University of Washington, Robert Findlay of Miami University of Ohio, and Margaret Palmer of the University of Maryland are trying to determine if different species of bacteria from different biological areas (or biomes) perform similar functions in breaking down organic matter that enters a stream. The implications of their search for what they call “functional redundancy” are enormous because the ability of bacteria and other microorganisms to degrade organic molecules is a critical aspect of ecosystem function. Simply put, it is how nature purifies water.

As humans turn more and more from chemical to biological filtration systems to purify their drinking water, treat their wastewater, and decontaminate their groundwater, they need a better understanding of how the organisms actually function.

Kaplan’s team is investigating such questions as, do different species of bacteria in different biomes perform the same function? If so, can species from one biome be put to work in another? What determines if an organic molecule or compound is biodegradable? Because bacteria appear to work in consortia to break down organic matter in water, what is involved in the complex process of transferring them from one biome to another? Kaplan’s team is studying one primary (and two secondary streams) in three very different regions: McDonald’s Branch in the Pine Barrens, White Clay Creek in Chester County, and Rio Tempisquito in Costa Rica.

McDonald’s Branch runs through a white cedar bog on New Jersey’s coastal plain. As a result, its water has high acidity, low amounts of dissolved oxygen, and high levels of organic carbon. White Clay Creek, in the hills and deciduous woodlands that characterize the Pennsylvania Piedmont has extremely high levels of nitrogen due primarily to the intensive farming practices on the surrounding land. Finally, Rio Tempisquito is found in a tropical evergreen forest in the Costa Rican mountains. Despite being surrounded by lush forests, the river has some of the lowest concentrations of dissolved organic compounds measured anywhere in the world.

By studying how each river’s microorganisms fare when transported to such different biomes, the scientists hope to better understand how the metabolizing functions work. This should shed new light on our efforts to clean up our water. In the search for knowledge about how ecosystems process organic carbon, Kaplan also hopes to gain new insights into the origins and fates of the organic pools in the earth’s oceans. Produced by the organic matter that flows through our rivers, these pools of dissolved carbon have a significant aggregate impact on global carbon cycles, which are believed to be a significant source of global warming.

Smelling Out Fragrances

Stroud Center scientist Laurel Standley is working on a research project with University of Delaware colleagues to determine whether household product fragrances are harmful to the environment.

In this research, as with much of her other work, Standley uses a mass spectrometer as her nose. This sophisticated and expensive machine identifies the types of particles present in a sample. The particles are ionized and beamed through a magnetic field which measures their mass, thus identifying them.

The Research Institute for Fragrance Materials, an organization formed by a consortium of chemical manufacturers, is funding the two-year project. The consortium is concerned about what happens to the fragrances in their household products after they are poured down the drain. In particular, they want to know what happens to the fragrances when they are spread on farmers’ fields in sludge from sewage treatment plants. Do the fragrances evaporate into the atmosphere? If so, is there any risk of accumulation in the atmosphere or in the tissues of humans and animals? Do the fragrances decompose harmlessly with the sludge?

“They want to make sure these things don’t become a problem,” said Standley. They don’t want to make the mistake that was made with PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls) and refrigerants, which were assumed to be harmless.

Standley explained that the fragrances are organic chemicals, many of which originate from plants. Vanilla is one example.

The scientists distinguish between fragrances and perfumes. The latter, Standley said, is made up of many components to produce a unique smell and are usually expensive. Fragrances are simpler, manufactured in bulk, and produced as cheaply as possible to make products more appealing to consumers.

Standley’s fellow team members from the University of Delaware are environmental engineering academics Herb Allen, Pei Chiu, and Dan Cha, and graduate student Angela DiFrancesco. They do most of the fieldwork, and the Stroud Center does most of the laboratory analysis.

An Alpine Perspective

For Luxembourger Tom Battin, the gently rolling hills around the Stroud Center are a long way from the glacial streams of the Austrian Alps, where he did his postdoctoral studies.

But sooner or later, any scientist who focuses on stream ecology is bound to encounter colleagues from the Stroud Center, considered one of the world’s leaders in the field.

That day came sooner than later for Battin when he met Stroud Center scientists Lou Kaplan and Denis Newbold at a 1995 conference of the American Society for Limnology and Oceanology. The following year, he took a six-month position at the Stroud Center to help with the “watershed tea” project, among other projects.

Now, after completing doctoral and post-doctoral studies at the University of Vienna and Innsbruck, he is back at the Stroud Center for at least a full year as a visiting staff scientist.

His focus on water grew out of an avid boyhood interest in dragonflies. He traveled around Europe — particularly the Mediterranean — collecting dragonflies and observing their life cycles. He studied zoology at college, and his master’s thesis at the University of Vienna concerned the “biogeography and systematics of dragonflies.”

Battin’s concentration narrowed further into the microworld of stream ecosystems. In addition to his current research at the Stroud Center, he is studying the biogeochemistry of Mediterranean streams for the European Union.

His research delves into the microbial communities of streams and the role such communities play in recycling solids in the water.

Microbes coat sedimentary particles in the stream, producing a slimy and slippery layer of what Battin calls “microbial biofilm.”

“I’m very interested,” he said, “in how the flow of the water influences the structure — architecture — of these microbial biofilms, and how the structure influences the functioning of the biofilms.”

His current stint at the Stroud Center was made possible through a grant from the National Science Foundation of Austria to do post-doctoral research in the United States for at least a year.

At the same time, he remains involved in the European Union-financed project to study small Mediterranean streams that, Battin said, “are heavily impacted by wastewater.”

Battin’s year at the Stroud Center ends in October, but he said he could extend it for six months or even another full year if necessary.