Matt Ehrhart. Photo: Dave Arscott

“It’s difficult to get long contiguous stretches of a watershed, particularly headwaters, restored,” says Matt Ehrhart, director of watershed restoration at Stroud Water Research Center.

It’s certainly ideal but also rare for all landowners along a stretch of stream to implement best management practices (BMPs) for water quality. At best, there may be a few scattered here and there.

However, the Stroud Center’s Watershed Restoration Group is building relationships with all of the farmers along two headwater tributaries to restore, protect, and monitor them.

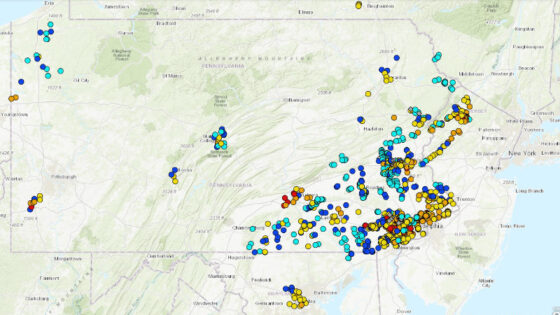

One is an unnamed tributary to Mill Creek in central Lancaster. The other, also unnamed, flows into Little Conestoga Creek in Eastern Pennsylvania. Both eventually lead to the Susquehanna River and Chesapeake Bay. They’re also impaired and targets of the Clean Water Act.

A Growing Partnership

Allowing livestock access to streams causes erosion, water pollution, and disease problems.

Some of the farmers participating in the project have already taken steps to reduce runoff and move cows away from the streams. By partnering with the Lancaster County Conservation District, the Natural Resources Conservation Service, Red Barn Consulting, Inc., and TeamAg, Inc., the Watershed Restoration Group will help farmers do even more.

“Our goal is to add forested riparian buffers along the entire length of these two stream stretches over the next two years. Buffers are highly effective, so they will play a key role,” Ehrhart says. “But buffers can become overwhelmed when used in isolation, so also important will be barnyard improvements for manure management, rain gutters and spouting, no-till farming, and grassed waterways.”

This is the same stream just one growing season after fencing to exclude livestock.

Improvements such as buffers are low-cost alternatives that take time to mature and reach their full potential. Associate Research Scientist John Jackson, Ph.D., says, “From our perspective, it’s better to address 10,000 feet of stream or 1,000 acres of farmland by using these low-cost BMPs than to address a much smaller area using more expensive solutions that maybe look good right away — because even if you do everything right in one location, if the farms upstream are polluting the water, it’s going to affect everyone downstream.”

TWO TRIBUTARIES, ONE LONG STUDY

The case for widely used low-cost BMPs would benefit from science that proves their value. The problem is that long-term data describing their effectiveness and how long it takes to restore an impacted stream are lacking.

In just two years, significant improvement can be seen. Photos: Matt Kofroth, Lancaster County Conservation District

Jackson and his team of researchers will fill the gap by studying the health of the two tributaries over many years, possibly decades. Right now, they’re in the process of establishing a baseline.

Stroud Center scientists like Jackson evaluate and help improve the condition of streams not by measuring one indicator or employing one cure-all method, but by using many tools all together. “It’s like the difference between only taking care of your heart versus your whole body.” Jackson explains. “Will your body be better off if you take care of your heart? Sure. But if you do that in isolation and neglect your lungs then your body may still suffer. The same is true for monitoring and restoring stream health.”

This project is unique in that it presents a best-case scenario. What happens when everything is done right to restore a stream?

“Different parties have different ways of measuring success,” adds Ehrhart, “For example, the biggest concern in terms of cleaning up the Chesapeake Bay is reducing nitrogen loads and then phosphorus and sediment. There are things that can be done on the landscape to reduce the amount of nitrogen flowing into a stream right away, but it can take decades to flush out sediment.”

“Everybody wants to know how long it takes to clean up an impacted stream. No one really knows. We’re changing that,” says Jackson.

Ehrhart agrees. “Yes, and we think the data will serve as an incentive for more landowners to implement BMPs.”