On a clear, bright day, Jennifer Matkov wades calf-deep in cool stream water.

“These are the beautiful fieldwork days we love!” she says.

She and fellow staff scientist Laura Borecki are using Stroud Water Research Center’s new Nikon Total Station survey equipment to survey the stream morphology — such as the shape of the streambed and its banks, the location of large woody debris and other features — of White Clay Creek.

How Long Does Stream Restoration Take?

Stroud Center’s Associate Research Scientist Melinda Daniels, Ph.D., is leading part of a study, now in its second decade, that seeks to answer the question: How long does stream restoration take after the planting of a streamside forest?

The project, funded by the National Science Foundation’s Long-Term Research in Environmental Biology (LTREB) program, provides support for Stroud Center scientists to measure changes in three separate 300-meter-long reaches of White Clay Creek.

One reach is maintained as an open meadow, a second as a mature forest, and the third was experimentally planted with a riparian (streamside) forest buffer 30 years ago.

Stroud Center scientists have hypothesized that stream widening following the growth of a streamside forest is an important initial phase in restoring streams to healthier conditions.

“By monitoring the same sections over a period of decades,” Matkov says, “we can observe long-term changes in the stream, and we can see if, and to what degree, the addition of a riparian buffer has altered the shape of the stream channel.”

CREATING A 3-D MAP OF THE STREAM

The Total Station is the same instrument engineers use to lay out roads and buildings. Researchers look through its lens and use sensitive focusing tools to take a “shot” of a reflective prism on top of a pole that is positioned at a point of interest. The Total Station records that location by emitting a laser that bounces off the prism and back to the base station. By recording the time and distance the laser travels, the base station calculates the point’s latitude, longitude, and elevation.

“We’ll shoot many of these points across the landscape and use those measurements to create a three-dimensional map of the stream and its features,” says Matkov.

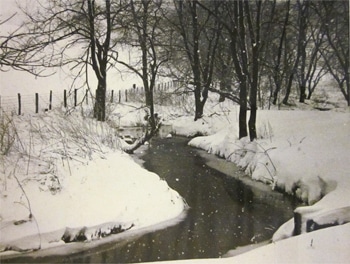

The same stretch of White Clay Creek behind Stroud Water Research Center, before being planted with an experimental streamside forest (left), and in 2013 (right).

SIGNS OF RECOVERY

The riparian planting is showing signs of recovery. Stroud Center scientists have observed that the stream is changing — becoming wider such that riffles are shallower with more rocks protruding out of the water and pools with a wide variety of depths. All of this provides more and better bottom habitat for stream organisms like algae, freshwater insects and fish.