Anybody who’s watched the film “Ratatouille” remembers its famous line “Anyone can cook!” but perhaps missed the true meaning of it. We scientists missed it too. Not everyone has the opportunity to become a professional scientist, but a great community scientist can come from anywhere. Anyone can be a part of science.

The Next Frontier in Environmental Science

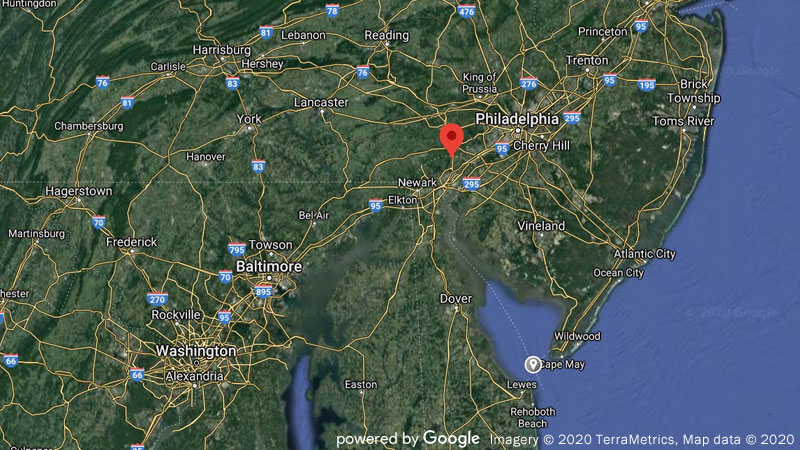

Since 2017, hundreds of volunteers have been monitoring water quality in Pennsylvania, Delaware, New Jersey, and New York as part of the Delaware River Watershed Initiative (DRWI). They are citizen scientists: curious and concerned citizens that with the aid of Stroud Water Research Center’s EnviroDIY™ technology are exploring the next frontier in environmental science.

Their collective data can lead to important discoveries with the help of professional scientists. Stroud Center scientists Diana Oviedo-Vargas, Ph.D., and Marc Peipoch, Ph.D., have compiled and analyzed water-quality data from over 70 sites from across the Delaware River watershed.

Instrumentation at the sites are maintained by citizen science group that are part of the DRWI, launched by William Penn Foundation to address primary threats to clean water in the watershed.

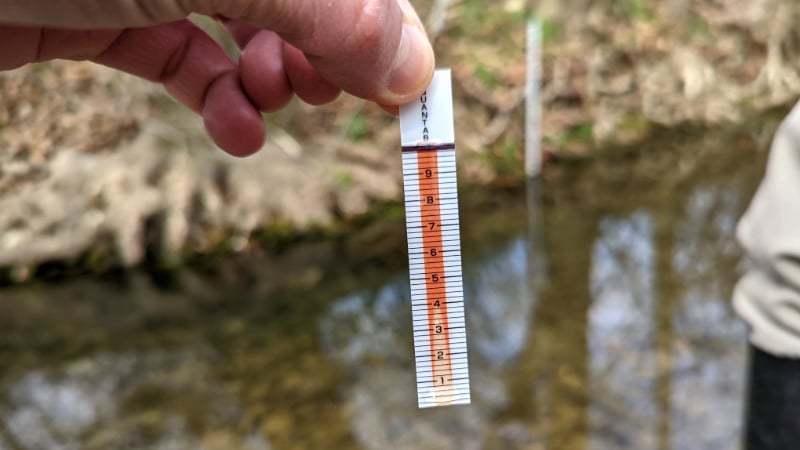

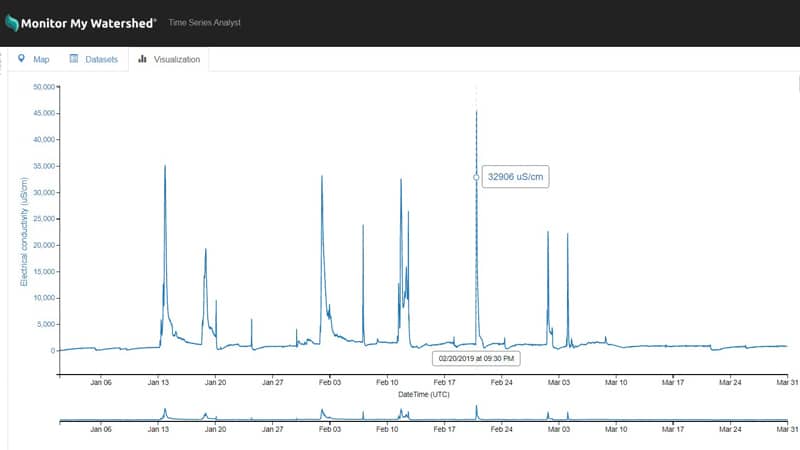

Two of the water-quality parameters measured by all citizen scientists across the river basin are water temperature and electrical conductivity. Water temperature is a key regulator of all biological activity and electric conductivity is directly related to the amount of dissolved salts (sodium, chloride, calcium, etc.) present in the water.

Striking Patterns Revealed

Preliminary analysis by Oviedo-Vargas and Peipoch has revealed striking patterns in these two parameters. Temperature data clearly showed thermal stress of trout populations in some headwater streams and gave insight into which streams might support the reintroduction of coldwater fish. This information will help communities and state officials restore and protect our fish populations.

On the other hand, peaks of electrical conductivity during winter storm events in urban streams across the watershed showed salt concentrations in the range of those at the mouth of the Delaware River estuary. When road salt runoff briefly turns freshwater streams into seawater, it hurts the stream macroinvertebrates that are critical for healthy streams.

This citizen science data is helping scientists and officials identify where these water-quality problems originate and how we can solve them.

These scientific findings are undoubtedly the product of avant-garde collaboration between scientific professionals and citizen scientists. No other kind of collaboration would enable a cost-effective monitoring of the nearly 15,000 square miles of the Delaware River watershed. Only a watershed monitoring effort powered by curiosity can reach that scale of scientific exploration.

Related News

Stroud Center Named Watershed Champion by Philly–Area Collaborative

Study: Community Science Can Aid Water Resource Monitoring

Volunteering With Scientists Changed How I Advocate for Clean Streams

We, the Community Scientists

EnviroDIY in the Delaware River Basin