By David Wise

What if we tried? That phrase comes up regularly when Matt Ehrhart, Lamonte Garber, and David Wise put heads together. For them, figuring out better ways of doing things is a fun part of their work — and integral to their team since 1997, beginning at the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. Their creative thinking covers many aspects of restoring forest buffers along streams, such as how to get farmers to say yes to forested buffers; how to elevate buffers as a priority in federal, state, and private conservation funding; and the seemingly simple detail of how to get trees to survive once planted.

The goal of improving the survival and growth of trees has persisted through it all. “We put a man on the moon in 1968 when I was 8 years old, but in 2000, we still didn’t know how to get streamside forests to grow,” says David Wise.

Early buffer plantings often had survival rates under 20%. The methods suggested by foresters working on timberlands with poor soils didn’t work on the deep, rich streamside agricultural lands where buffers were needed.

Bern Sweeney, Ph.D., former director and distinguished research scientist of Stroud Water Research Center, was asking many of the same questions about streamside forests and using his evenings and weekends to conduct field trials of reforestation methods. In 1989, he was one of the first in North America to test the idea of using tree shelters, which had recently been developed in England for reforesting active sheep and goat pastures, to protect streamside tree seedlings from deer, rabbits, vines, and the like. He combined this with insights from nursery growers and orchardists on how herbicides could help keep rodents from damaging fruit and ornamental trees in their nurseries. Early field trials that focused solely on either shelters or herbicides gave way to larger, more complicated trials involving both methods at once. The relationship between the green industry and the Stroud Center flourished, and buffer reforestation methods did too.

In 2013, Ehrhart and Wise began working at the Stroud Center in what would become known as the Robin L. Vannote Watershed Restoration Program, with Garber joining soon after. Their expertise added to Sweeney’s efforts to improve reforestation methods. The greatly expanded field effort of the team to restore forest buffers on many sites throughout Pennsylvania and the mid-Atlantic region provided dozens of opportunities for tweaking the installations at little or no additional cost in order to explore basic research on how to improve overall success on the installations. The team recruited interns, graduate students, partners, and volunteers to help collect the data. This, combined with the expertise of other Stroud Center scientists and statisticians, enabled them to analyze the outcomes and answer basic questions that were perplexing conservationists as they attempted to reforest streams and rivers locally, regionally, and throughout the world.

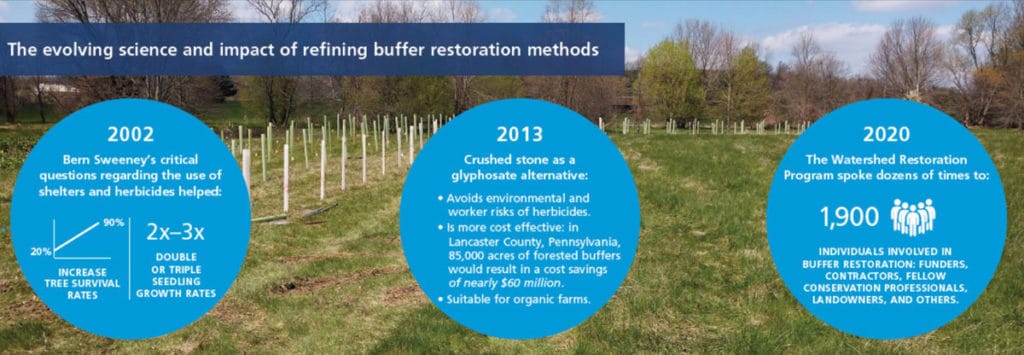

By 2002, Sweeney had already answered numerous critical questions regarding the use of shelters and herbicides, helped take tree survival rates from below 20% to about 90%, and helped double or triple seedling growth rates.

Yet with every advance, new questions arose: How do you keep the nets used on tree shelters, which protect birds from falling down the tubes, from tangling a tree’s growing tip and permanently disfiguring and weakening the tree? In response to that question, Sweeney developed multiyear field trials and, with the help of a graduate student, developed a simple solution by adjusting the way the netting was placed on top of the shelter to give the seedling a small exit hole the size of a half dollar.

Subsequent large field trials explored which of the many brands of tree shelters were best for local conditions. To find the answer, Sweeney and his team evaluated the survivorship and growth of different brands of tree shelters in experimental side-by-side comparisons.

Other studies involved strategically removing shelters at various stages of seedling growth to determine when and how to remove tree shelters safely in order to avoid tree death due to antler rub by adult deer. Additional field trials were needed to figure out how to protect shrubs with multiple stems using short 2-foot shelters from deer when the field data showed them not doing well in the 5-foot-tall shelters.

In many cases, what seemed like simple questions turned into large field trials involving thousands of seedlings, as was the case in figuring out what kind of shelter stakes were needed to keep seedlings from snapping in flood-prone areas along streams and rivers. Another difficult issue was to determine if reforestation was even possible on streamside areas where thick deposits of sediment had accumulated due to the previous existence of milldams. The answer was yes, but finding the answer required three to five years of data and dogged determination to see things through — so, too, did the many other questions.

Through the years, many answers have become clear. Some have required both forest buffer practitioners and funders to rethink standard practices. For example, Sweeney’s 2002 breakthrough publication revealing that spraying herbicides around sheltered trees could keep most herbivores and invasive plants from killing seedlings would greatly help practitioners to petition government funding agencies to support the cost of shelters and use of wetland-safe forms of glyphosate (like Rodeo) as part of the standard best management approach to buffer installations.

By 2013, the Stroud Center was looking for alternatives to using glyphosate because of concerns over the environment, worker exposure, and how to reforest streams on organic farms. Sweeney and the team began field trials of multiple options. Three successive generations of field trials, each several years long, have now shown that the use of crushed stone (specifically, 2A modified stone, a mixture of coarse and fine stone material) around the base of shelters can protect seedlings from rodents and invasive plants about as well as herbicides do. Beyond avoiding the environmental and worker risks of herbicides, the stone mulch is cheaper — about one-third the cost of herbicide applications — and seems to provide longer lasting protection. If, for example, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, implements the 85,000 acres of forested buffers called for in official water quality cleanup plans, the cost savings would amount to nearly $60 million.

These insights and successes underscore the value of coupling Stroud Center research with on-the-ground restoration. Through the Stroud Center’s education and outreach efforts, other organizations have learned this as well. In 2020, the Watershed Restoration Program spoke dozens of times to audiences of more than 1,900 individuals involved in buffer restoration: funders, contractors, fellow conservation professionals, landowners, and others. Many of these presentations included information generated through research on buffer restoration methods.

According to Ehrhart, “Our work perfectly integrates the three parts of the Stroud Center’s mission ‘to advance knowledge and stewardship of freshwater systems through global research, education, and watershed restoration.’ Not only are we investigating how to better restore our freshwater resources, we are putting what we learn into practice and sharing our knowledge with others who we hope will do the same.”