After Examining Water Quality Data From Community Scientists, Researchers Say It Has Value, but Volunteers Need Support

Community science is on the rise. It’s a potentially fast and affordable way to scale up data collection, but is crowd-sourced data any good? Professional scientists might be skeptical. However, a new study has found that with the use of autonomous sensors, community scientists can collect high-quality data for one of the most difficult things to monitor — water resources.

To understand the value of community science in monitoring the health of streams and rivers, researchers from Stroud Water Research Center have examined the quality and usability of water quality data collected by volunteers using autonomous sensors. Their findings, which were published in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, show some of the data is high-quality and fills in gaps that could support the work of professional scientists, agency professionals, and community activists. However, additional infrastructure and support are needed to fully realize the data’s potential.

The conclusions come from an analysis of the largest known community science project to monitor water quality using real-time sensors. More than 50 watershed organizations launched EnviroDIY in the Delaware River Basin in 2016 as part of the Delaware River Watershed Initiative, a collaborative effort to conserve and restore the streams that supply drinking water to 15 million people across Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, and New York.

Since then, volunteers have deployed and maintained more than 100 stations that monitor temperature, electrical conductivity, depth, and sometimes turbidity. The high-frequency data from these monitoring stations is captured continuously at regular intervals — about every 5 to 15 minutes.

The researchers compared the community science-led stream monitoring network with the basin’s U.S. Geological Survey streamgaging network. They found that community scientists added data that enhanced, rather than duplicated, existing federal data to provide a more comprehensive understanding of pollution sources. The community scientists added data from urban and suburban communities, whose watersheds are more impacted by humans and traditionally underrepresented by government-led monitoring efforts, and they captured data from streams that are smaller than those typically monitored by USGS. Small streams provide important wildlife habitat and are critical to downstream water quality.

These findings, they note in their paper, are likely due to volunteers choosing to monitor streams they perceive as polluted and comparing them to ones they expect to be clean.

Data Quality

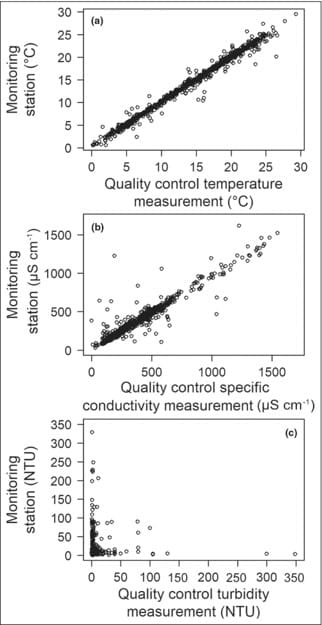

Data quality varied depending on the level of skill and maintenance required for accurate capture. Specifically, temperature and electrical conductivity data were high-quality, but turbidity data captured using optical sensors without self-cleaning wipers required further quality control.

Challenges and Needed Investments

Although the data can be accessed and used from the online portal Monitor My Watershed, community scientists had difficulty sharing information about site visits, maintenance, and data issues that would provide the quality assurance and quality control needed for others to use the water quality data. They also had difficulty analyzing their data to understand threats to water quality without the support of professional scientists.

The researchers say challenges with quality control and interpretation — as well as with the creation of graphs and other means of visualizing results — could be overcome with the development of accessible web-based tools.

“Autonomous sensor networks are a relatively low-cost technology that can help people monitor the streams and rivers in their communities. With more training for community scientists and relatively small investments in technology infrastructure, the data they collect can become more useful to them and anyone working to conserve and restore water resources,” said Diana Oviedo Vargas, Ph.D., assistant research scientist at the Stroud Center and the lead author of the paper.

Support High-Quality Science

Data collection using autonomous sensors is cost-effective but not free. Volunteers need training, equipment needs purchasing, and we conduct quality controls and analyses to use sensor data in scientific research. To support high-quality science, donate today.