As Recognition of Forever Chemicals Grows, Local Research Seeks Solutions

By Diana Oviedo Vargas, Ph.D., and Diane Huskinson

What Are PFAS?

PFAS stands for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances and refers to a class of human-made chemicals that includes over 12,000 compounds and growing, produced intentionally or unintentionally over the last 80 years.

These chemicals are widely used in the manufacturing of goods because they are stable at high temperatures and can repel water, stains, oils, and other chemicals — making them popular in industries producing easy-care products like nonstick cookware and water- and stain-resistant fabrics and rugs. Add to that food packaging, pesticides, adhesives, paints, cosmetics, shampoos, and much more.

How PFAS Enter the Environment

PFAS are released into the air and water during, and as a byproduct of, manufacturing. They are also released during the regular use and disposal of PFAS-containing products, such as when pesticides are applied to farm fields or toilet paper is flushed. Once released, they stick around for a long time — perhaps longer than a thousand years.

That longevity allows these so-called forever chemicals to accumulate in nature and in the human body. According to a recent study, the global environmental spread of PFAS has led to levels exceeding drinking water standards around the world — even in remote places like Antarctica. Other studies have found that between 95% and 100% of Americans have PFAS in their blood.

It should not be surprising then that 200 million Americans are exposed to PFAS in drinking water or that foods including freshwater fish are contaminated with PFAS.

Health Risks From PFAS Exposure

Studies have shown that some PFAS are linked to health problems including thyroid disease, increased cholesterol levels, liver damage, and kidney cancer. Therefore, over the past several years, PFAS have increasingly garnered public, scientific, and regulatory concerns.

Regulations Limiting PFAS

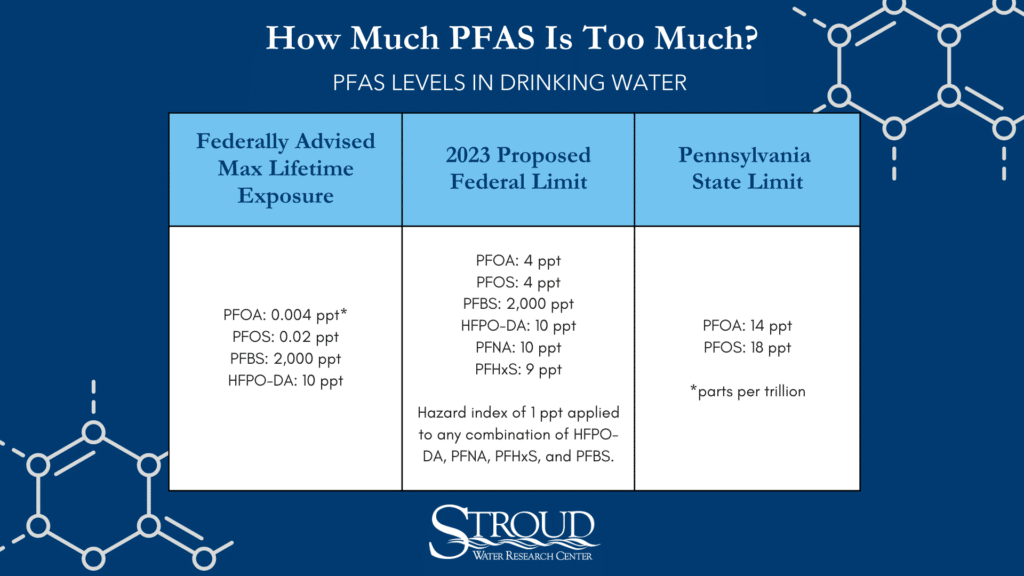

Currently, there are no federal standards limiting the level of any PFAS in drinking water. In March of 2023, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency proposed a National Primary Drinking Water Regulation to establish legally enforceable levels, called maximum contaminant levels, for six PFAS in drinking water: PFOA, PFOS, PFNA, HFPO-DA (commonly referred to as GenX Chemicals), PFHxS, and PFBS. If finalized, they will represent the first new federal drinking water standards for any contaminant since 1996, when the current process for establishing such standards was enacted.

In the meantime, there are health advisory levels set by the EPA. Although not enforceable by law, they serve as a guidance threshold under which no adverse health effects are expected over a specific period of exposure to contaminated drinking water.

The EPA issued the first of these health advisory levels for two PFAS compounds (PFOA and PFOS) in 2009. They were updated in 2016 and again in 2022 to include two more compounds (PFBS and HPFO).

Some states have taken matters into their own hands, setting maximum contaminant levels in drinking water and outright banning PFAS in products such as food packaging.

Pennsylvania, for example, set enforceable limits for two PFAS (PFOA and PFOS) that will require water system monitoring starting in 2024 for those serving more than 350 people. Smaller systems must have monitoring in place by 2025. However, the state allows higher levels of PFAS than what the EPA is recommending.

PFAS Research

Biosolids, a nutrient-rich byproduct of wastewater treatment, are sometimes applied to soils as fertilizer instead of being disposed of in a landfill or incinerated. However, such applications may be a significant source of PFAS in soils and water.

Scientists from Stroud Water Research Center and Center for PFAS Solutions are investigating new techniques for analyzing biosolids for PFAS contamination before they are distributed to farmers. The ability to identify and track PFAS-rich biosolids efficiently and inexpensively could prevent their use on land, while allowing continued use of screened biosolids in place of chemical fertilizers.

Research at the Stroud Center includes measuring PFAS concentrations in the soil and surface water from a select number of Pennsylvania farms. Results from this project should be finalized in late 2023. To stay up to date on this research, subscribe to receive the Stroud Center’s newsletter.

What You Can Do

- Learn what your state is doing.

- Limit your exposure to PFAS.

- Support research, education, and restoration that advances knowledge and stewardship of fresh water.

Puedes encontrar más información en español sobre este tema aquí.