Whether it’s too much, too little, or too dirty, the primary way humans experience climate change is through water. Streamside forests can help.

More Than Filters

Riparian forest buffers have long been heralded for doing what their name suggests — buffering waterways from pollution. Storms carry sediment, nutrients, and other pollutants from the landscape into the low-lying areas where streams and rivers flow. Forests help by slowing that polluted stormwater down, allowing it to be absorbed into riparian soils and excess nutrients in the water to be taken up by plant roots and used like fertilizer.

But to call them buffers is somewhat of a disservice. These hard-working strips of vegetated land do so much more. They provide food and habitat for wildlife. They replenish groundwater. They stabilize streambanks, reducing erosion and sedimentation of streams. They help to manage the flow of water during wet and dry weather extremes. And as more people grapple with climate change, their ability to absorb carbon and act as shields against rising temperature becomes more valuable.

It’s Getting Hot in Here

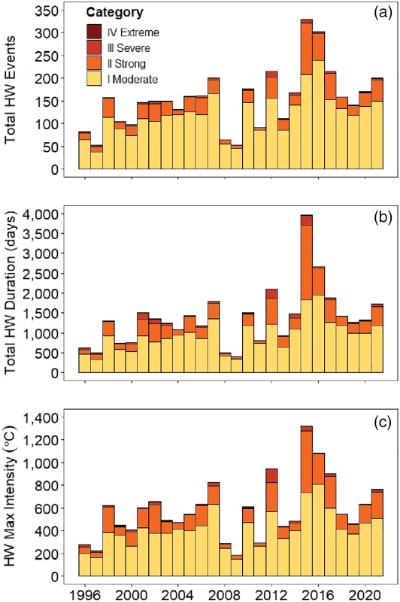

In June of this year, nearly 5 billion people worldwide suffered from extreme heat driven by climate change, according to a Climate Central report. In the United States, 165 million people were affected.

The frequency and intensity of extreme heat is only increasing and resulting in a rapid rise in heat-related deaths. Heat waves in U.S. cities, for example, are occurring three times as often as they did in the 1960s. Groups most at risk to heat include children, pregnant women, older adults, people with pre-existing conditions and disabilities, and many others.

Terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems are also feeling the heat. Remember Australia’s Black Summer? The Land Down Under is no stranger to bushfires, but in 2019 and 2020, record-breaking heat and dry weather fueled by climate change killed an estimated 3 billion animals. A year later, a heat dome along Canada’s Pacific coast likely killed more than 1 billion marine animals. Freshwater ecosystems are vulnerable to heat too, as reported by Stroud Water Research Center and others.

Sweet Relief

Streamside forests can significantly improve water quality; it’s what buffers are so well-known for. But their impact on temperature deserves more attention. Tree shade and transpiration from plant leaves keep stream temperature cooler and more stable.

Their cooling effect can also reduce the toxicity of some pollutants in the face of climate change. In a Stroud Center study, scientists John Jackson, Ph.D., and Dave Funk found that salt pollution is a greater threat to aquatic species as streams get hotter.

Even in winter, forest buffers could make stream ecosystems more resilient to climate change. Another Stroud Center study showed, with help from visiting scholar Allison Kolpas, Ph.D., that the pause in mayfly development over winter helps all the individuals in a population match their timeline for emergence. This matters because mayflies not only signal stream health; they are an important food source for fish.

Trees protect terrestrial wildlife from climate change too, particularly in the boreal forests, where the warming rate in protected areas is up to 20% lower than in surrounding areas that are often converted to other land uses.

For humans, trees lower heat stress more so than artificial shade, according to some studies, and they reduce energy uses that cost money and contribute to climate change.

Easing Water Woes

At the center of the climate crisis is water. Whether it’s too much, too little, or too dirty, the primary way through which humans experience climate change is through water. Streamside forests can help. Besides keeping water cleaner, forests can dampen the impacts of storms and droughts.

Researchers at North Carolina State University, for example, studied how forest buffers might mitigate predicted climate change impacts in a rapidly developing watershed near Raleigh. While not a silver bullet, streamside forests are capable of reducing flooding in the areas where they are planted, the researchers found.

What You Can Do

Whether you live and work near a stream or not, you can plant native trees that will provide wildlife habitat, keep neighborhoods cooler during hot weather, and help make our water more resilient to climate change. For greater success, learn about planting and maintenance techniques that increase tree survival rates and the research that informs them:

- Doing Good Better: Refining Buffer Restoration Methods

- Cutting Waste in the Reforestation of Riparian Zones

- How Many Trees Does It Take to Protect a Stream?

- Check out watershed restoration fact sheets and videos to help you plant and maintain native trees.