By Diane Huskinson

The Beginning of an Adventure

“The word adventure has gotten overused. For me, when everything goes wrong — that’s when adventure starts.” — Yvon Chouinard, Founder of Patagonia

Like the mountain road that led Stroud™ Water Research Center scientists to their Costa Rican study site twice already this year, the way to scientific discovery is often long, bumpy, unpredictable, and fraught with obstacles. But as with any epic adventure, there was a reward worthy to be earned. Across borders, over mountains, and through woods and waters they traveled in search of their golden chalice: fish — and macroinvertebrates too.

“It’s a miracle we all got there in one piece,” says Willy Eldridge. The voyage was straight out of an Indiana Jones film. Leaving the comforts of home in the suburbs of Chester County, Eldridge and his colleagues journeyed deep into a thick, steamy rainforest — by air, land, and sea — to the distant land’s southwestern edge where it meets the Pacific Ocean.

After flying into San Jose on a rare clear and bright August morning during the height of the rainy season, Eldridge along with Dave Arscott, Laura Borecki, all of Stroud Water Research Center, and Win Fairchild, a professor at West Chester University who volunteered his services for the chance to visit Costa Rica, were to meet up with Rafa Morales, the station manager and a researcher at the Maritza Biological Station. But first, they had to find him. Alas, the international coverage on their prepaid phones failed, and a sea of taxis and tourists flooded the area outside the airport. With nightfall looming and another 6 ½ hours of rugged terrain to cross, they had no time to waste.

They spent the next half-hour weaving through the crowds and hauling their luggage and gear. At last, they spotted Big White, the white Toyota Land Cruiser that Morales drives, circling the airport. Eldridge ran down the road after Big White, excited by the miracle of finding Morales. This lucky encounter was to be an omen of things to come.

In Arscott’s estimation, “The rig was the old-school type. It had bench seating, so we had to sit sideways traveling over winding mountain passes and along dirt roads through the rain. There were people in the road walking and on bicycles and dogs and chickens aimlessly meandering about. It was stop-and-go and bumpy for about 6 hours. It made your stomach woozy.”

Big White would take them to the town that would serve as their home base, Sierpe de Osa. The town rests at the end of a road on the banks of the Río Sierpe, which empties into the Pacific Ocean.

“Few tourists spend more than a night in Sierpe. It has more in common with Iowa than Eden,” says Eldridge. A small town with few attractions to entice tourists, Sierpe is more of a gateway than a destination. In Sierpe, people can catch a boat taxi that will take them through the mangrove forests at the mouth of the Río Sierpe to the Osa Peninsula, the ecotourism capital of Costa Rica and a jewel in the crown of biodiversity.

Lush, Diverse, and Threatened

The National Biodiversity Institute (INBio) of Costa Rica reports that this tiny country, which makes up 0.03 percent of the earth’s surface, is home to nearly four percent of all species estimated worldwide. “Its geographic position, its two coasts and its mountainous system, which provides numerous and varied microclimates, are some of the reasons that explain this natural wealth, both in terms of species and ecosystems,” reads the INBio’s website.

The value Costa Rica places in its natural assets and ecotourism industry is evidenced in the establishment of the largest national parks system in Central America as well as protected lands that make up 25 percent of national territory. However, certain poorly regulated practices in another booming industry could threaten more than the environment.

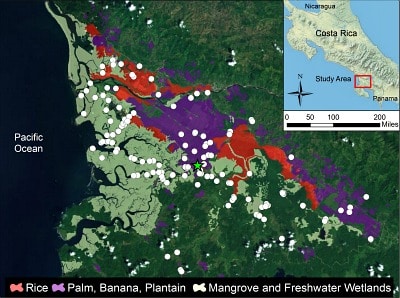

Costa Rica’s high annual rainfall makes it well suited to agriculture. The Río Sierpe used to be surrounded by banana plantations, but much of the agriculture has shifted to rice and African palm. According to the Agricultural Statistical Bulletin No. 20, produced by Executive Secretariat for Agricultural Sector Planning (SEPSA), in 2009 Costa Rica produced more than 564 million pounds of rice.

Rice is a staple in the Costa Rican diet, but so is seafood, and the pesticides and other contaminants from agriculture in the surrounding watersheds pose an unknown threat to terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems and to humans who eat contaminated fish and shellfish.

So Eldridge and his colleagues headed to the Río Sierpe and Grande de Terraba watersheds to identify contaminants as well as contaminated species that threaten humans who consume them. Each morning they would venture out by car, boat, and kayak to collect fish, macroinvertebrates, and clams next to farms and downstream in the mangrove forest preserve known as the Terraba-Sierpe National Wetland.

Laura Borecki and Dave Arscott paddling to a sampling location in a tributary of the Rio Grande de Terraba downstream from intensive rice agriculture.

“We already know from previous studies that contaminants can move beyond the original application site, propelled by wind or rainwater runoff to nearby and far off lands, freshwater habitats where there may be fishing, and drinking water supplies. This process is amplified when pesticides are applied by plane,” says Eldridge, who is an assistant research scientist at the Center and the principal investigator for the study.

“Pesticides applied to rice fields have a high potential to enter nearby waterways because of the wet conditions in which most rice is grown, and the farms are usually adjacent to streams and rivers. Rice also requires more pesticides than other crops. The beauty of this research is that what we discover will help us better understand how agriculture impacts streams and rivers, the ecosystems within the streams and rivers, and human health not just in Costa Rica, but here in Pennsylvania and elsewhere. That’s because the principles that dictate how streams and rivers work are applicable everywhere.”

The study is funded with a grant from the Blue Moon Fund, a landscape conservation group that focuses on regions of high biodiversity in Asia, North America, and the Tropical Americas.

With help from the Rainforest Alliance and the Sustainable Agriculture Network (SAN), organizations that have experience with the local farming practices, the scientists pulled together a list of pesticides used in the area.

To identify the species that are most likely to pose the greatest threats to humans, they consulted a list of fish of the Río Sierpe, which they generated during a 2009 study (view the water quality study report). They wanted to target fish and macroinvertebrates that are more fatty and longer living because pollutants are often stored in fat and increase within an organism as it grows. Aquatic organisms may bioaccumulate environmental contaminants to more than 1 million times the concentrations detected in water.

Science With an Impact

The team then hit the streets to visit local markets to speak to fishermen and merchants about the most popular choices for consumers.

“When you’re working in the lab, it’s all about the science,” Eldridge muses, “but when you talk to people, you see how the science has the potential to impact lives. You hear people’s stories, and several men I spoke to expressed their concerns about contaminated water and fish.

“Many people near Sierpe are fishing guides or commercial fisherman, or they fish to feed their families. They told us stories about fish dying just a few weeks before we got there when the planes spread pesticides over the rice fields. They even showed us pictures of some of the dead fish. But they felt powerless to do anything.”

Others recognize the risks and welcome advice from organizations such as the Rainforest Alliance. Herman Fabrega, a rice farmer near the Terraba River, limits impacts to streams and rivers by using less harmful pesticides. He also applies them when it is not raining and when nearby tidal streams are empty to reduce the chance that fish will be exposed and either die or accumulate harmful chemicals. By working with farmers like Fabrega, Center scientists can help further improve farming practices.

The stories the scientists heard made all the more clear the need for this research. Long-time resident Marcelo Aurigos is a clammer and fisherman on the island of Boca Zacate in the mouth of the Río Sierpe and five miles downstream of the nearest farm. He remembered the last time he had seen a fish kill by his farm: precisely 27 years ago, just before the banana plantations moved out. “Conditions are better now than they were 30 years ago, but with our study, we can give the Rainforest Alliance the information needed to guide farmers toward more sustainable agricultural practices,” Eldridge says.

Marcelo was a valuable informant and even helped the scientists find and collect one of the most locally prized clam species: the mud cockle, known locally as piangua, which is a delicacy in Costa Rica often eaten in ceviche. Another resident who played a leading role in the trip’s success was Geovanni Jimenez, the team’s boat driver and travel guide.

Each day for a week, the researchers made the journey from their lodgings in Sierpe de Osa to their field sites, where they would fish as the locals do, first by catching their bait — at least a pail full of red-faced crabs or freshwater prawns. Geovanni showed them the art of line fishing by hand.

“The local guides were essential for getting us to the right spot at the right time, but the fish didn’t always cooperate.” There are no roads to the big streams where the more desirable species are found, and access by boat must be timed with the tides.

In the evenings, they returned to an outdoor pavilion in Sierpe de Osa to process the fish under the light of the moon and a bare 60-watt bulb. Into a rhythm they sank: fish by day, process by night. Repeat.

All the while, the mosquitoes obligingly kept them company. “You can’t put on bug spray because it contains the very chemicals that are potential contaminants in the fish, and you can’t swat them because you are wearing gloves and holding a knife,” Arscott says with a laugh.

Yet the crude conditions didn’t stop the scientists from maintaining sterile technique. Every knife, every cutting board, anything that came into contact with a fish during processing was cleaned before reuse to prevent cross-contamination.

By the time they were ready to return to the U.S., they had collected 170 specimens from 25 species. Some came from fresh water and others from saltwater. There were some adults, some fry. Some sessile, like clams, and some motile, like the black snook. The researchers collected multiple individuals from the same places to capture the natural variability. Plus, chemical analyses require a minimum amount of tissue, so they needed a dozen or more of the smaller species like freshwater prawns.

Assistant Director and Research Scientist Dave Arscott explains further, “If you only go out and catch the biggest black snook you can find, you’ll have too many unanswered questions. How long has the fish been exposed to a particular pesticide? Where did that pesticide come from, and was it in the water or the food the fish ate? If the food, then was that food consumed as an adult or prior to adulthood? All of these variables are important because they will drive our interpretation of these data.

“The other issue is that there may be cause for concern about contaminants that originate from outside the local area. What’s happening locally is only a piece of the puzzle. That’s one reason why we collected samples from both sedentary and mobile species — to get a comprehensive picture of not just local but regional threats.”

Eldridge adds, “Really, every fish is potentially linked to a health risk because when they cast their nets, they keep everything from small minnows to clams to snapper. The local people are hugely dependent upon fish and shellfish from this mangrove system.”

The study will do more than identify health risks, however. Since rice is one of the country’s most widely farmed crops, related farming practices can have a significant environmental influence. In fact, La Nación, Costa Rica’s largest newspaper, recently reported on multiple land uses that are draining wetlands and invading protected areas in the Río Sierpe watershed. Rice planting was one of them.

That’s got the SAN looking to develop standards for rice farming as part of the Rainforest Alliance Certified Farms program. Oliver Bach, the SAN’s standards and policy director, is relying on the Center’s team of researchers to provide data that will guide those new standards.

“Our standards for Rainforest Alliance Certified products are not currently suitable for irrigated or wet rice plantations. You see, water is a much more mobile medium than soil, so I am grateful the Stroud Water Research Center can help,” says Bach.

Read the Stroud Center’s report to the Blue Moon Fund: “Preliminary water quality study of the Rio Sierpe and its tributaries.”