By James G. Blaine, Ph.D., and Lamonte Garber

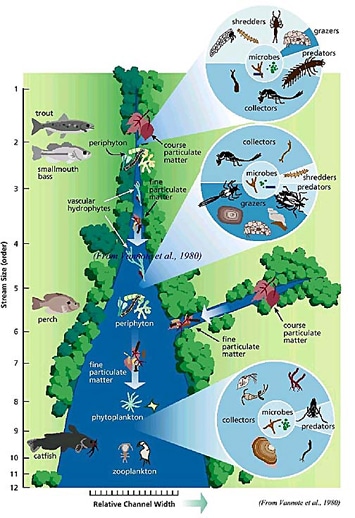

“FROM HEADWATERS TO MOUTH, THE PHYSICAL VARIABLES WITHIN A RIVER SYSTEM PRESENT A CONTINUOUS GRADIENT OF PHYSICAL CONDITIONS … WE REASON THAT PRODUCER AND CONSUMER COMMUNITIES CHARACTERISTIC OF A GIVEN RIVER REACH BECOME ESTABLISHED IN HARMONY WITH THE DYNAMIC PHYSICAL CONDITIONS OF THE CHANNEL.” — ROBIN VANNOTE, Ph.D., THE RIVER CONTINUUM CONCEPT (1980)

The publication of the River Continuum Concept 40 years ago changed forever the world’s understanding of streams and rivers. In it, the Stroud Center’s Robin Vannote and his colleagues describe the river itself, from its headwaters to its mouth, as a single, albeit ever-changing, community of living organisms. Indeed, the entire watershed, land and waters, is to be understood as an interconnected community in which a change to one part ripples through the entire system.

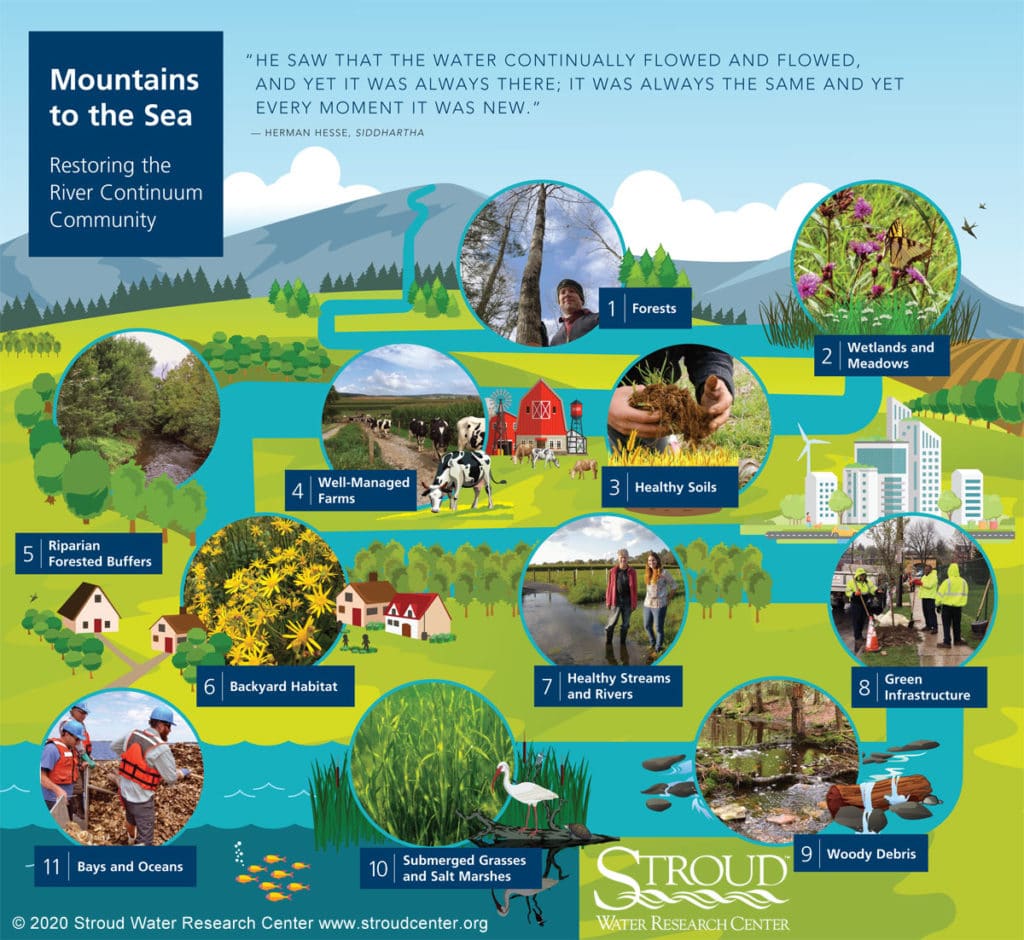

For millions of years before the advent of human civilization, rain fell to earth and then moved through a matrix of forests, wetlands, and thriving streams and rivers before ending its journey in one of the planet’s five oceans. Recreating parts of this once-massive “green sponge” on our heavily deforested, farmed, and developed landscape is both the art and science of restoration. It is also, as we will see on the next two pages, critical for the protection of clean water.

Because the Stroud Center’s Robin L. Vannote, Ph.D., Watershed Restoration Program believes that humans are a central part of the watershed community, the staff works with our partners and land users to implement natural solutions to regenerate soils and safeguard fresh water, solutions that benefit both human communities and the entire ecosystem.

“We are particularly active with farmers,” says Lamonte Garber. “They manage nearly a billion acres in this country, and restored habitats on their farms can transform the landscape and contribute constructively to issues ranging from soil health to climate change.”

1 | Forests

Forested watersheds produce cleaner fresh water than any other land use. We need to preserve existing forests, restore previously wooded lands, and sustainably manage timber.

2 | Wetlands and Meadows

These ecosystems are critical habitat for many plants and animals. They support pollinator plants, recharge freshwater sources, mitigate flooding, and protect endangered wildlife. Photo: Stephanie Eisenbise

3 | Healthy Soils

Healthy soils on cropland and pasture improve water infiltration and reduce runoff. No-till planting and cover cropping also improve agricultural productivity.

4 | Well-Managed Farms

Structural and management improvements on farms — including contour planting, grass waterways, and filter strips — control erosion and reduce runoff to streams.

5 | Riparian Forested Buffers

Streamside trees are the life-support system for streams and rivers, providing shade, food, and habitat for all life. Trees are the essential “cover crops” for our floodplains. Photo: M. Royer

6 | Backyard Habitat

Homeowners can help restore watersheds by replacing lawns with wildflower meadows, capturing rainwater, and using native plants, which also support pollinators and birds.

7 | Healthy Streams and Rivers

The capacity of streams and rivers to process pollutants in the water, from neutralizing nitrogen to consuming organic matter, is a crucial ecosystem service, which sends cleaner water downstream and reduces the treatment costs of our drinking-water supply systems.

8 | Green Infrastructure

Communities can implement rain gardens, pervious pavements, green roofs, and street trees to reduce the volume of stormwater reaching streams and sewage treatment plants. Photo: City of Lancaster, PA

9 | Woody Debris

A tree that falls into a stream bestows its final gift to the ecosystem, creating new fish habitat and a more diverse streambed. Fallen trees should be removed only if they are a hazard.

10 | Submerged Grasses and Salt Marshes

Restoring submerged aquatic vegetation is key to restoring estuaries like Chesapeake Bay. These underwater meadows are nurseries for young fish and crabs, provide food for waterfowl, and slow erosion. Photo: Chesapeake Bay Program

11 | Bays and Oceans

Every stage of the stream’s journey impacts the ocean into which it ultimately flows. Reducing pollution, combined with restoring diverse natural habitats — such as oyster reef replenishment pictured here — is critical to the health of the entire system. Photo: Chesapeake Bay Foundation

Get Involved

Stroud Water Research Center works hand in hand with landowners, helping them use their land more effectively through whole-farm planning and watershed stewardship. Visit stroudcenter.org/restoration for more information.

This article was originally published in Stroud Water Research Center’s 2019 annual report.