Welcome to a special issue of UpStream Newsletter. Here we take a closer look at the effects of road salt on our streams and rivers and how volunteers and organizations throughout the Delaware River watershed are working together to monitor what’s happening to their freshwater resources.

Last week’s snow and ice brought more than risky road conditions to the mid-Atlantic region. State, municipal, and private trucks spread tons of salt and brine along roadways to protect public safety. This Sunday, more of the same is expected. The unintended consequence, however, is the risk to the environment, including sources of drinking water.

To combat this threat and others to freshwater streams and rivers, Stroud Water Research Center is guiding an effort to mobilize and train a network of volunteers, currently more than 160 strong, throughout the Delaware River basin to monitor water quality. EnviroDIY in the Delaware River Basin includes 120 sites and utilizes the Stroud Center’s EnviroDIY Monitoring Stations to collect data in real-time. The data can then be viewed anywhere in the world on Monitor My Watershed®, an online tool for sharing and visualizing environmental data.

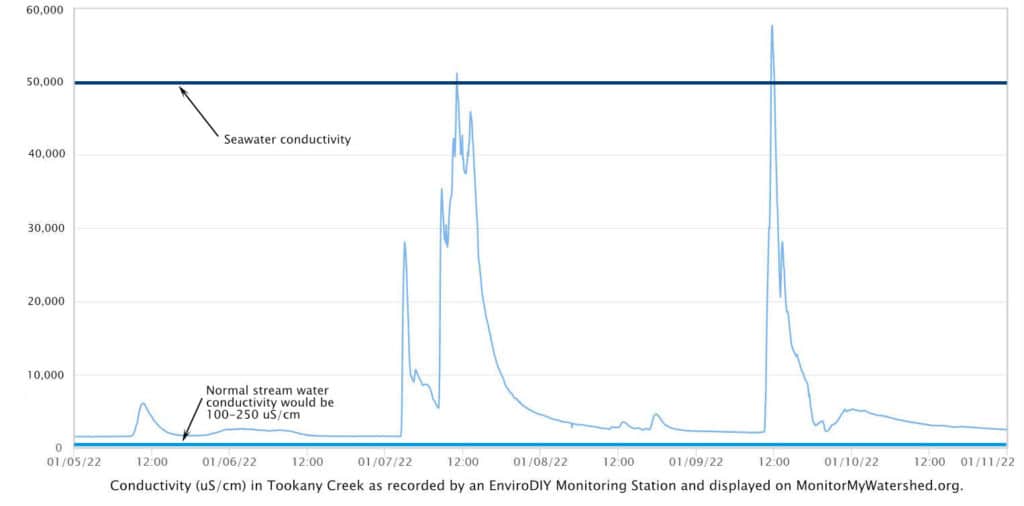

Volunteers with Tookany/Tacony-Frankford Watershed Partnership (TTF) in Philadelphia have measured electrical conductivity, which rises with salinity, as high as 58,000 microsiemens per centimeter — higher than typical seawater — after winter storms.

“Fresh water should measure between zero and 250 for most streams in our region,” says John Jackson, Ph.D.

Similarly, near-seawater conductivity spikes have been measured in some tributaries to the Brandywine, Chester, Tacony, and Wissahickon creeks, and half-seawater spikes have been measured in other tributaries to the Brandywine, Tacony, and Cobbs creeks.

In addition to measuring electrical conductivity, the volunteers measure water temperature, stream water level, water clarity, and more.

In reviewing the data collected by these volunteers and others, Jackson observed an alarming trend: salt concentrations in some streams remain elevated year-round. Other scientists have observed the same trend in other areas. Worse yet, published research from Jackson and entomologist David Funk indicates that salt is even more toxic to aquatic life during summer months when the stream water is warmer.

“Without these volunteers and the large network we are building,” says Jackson, “it would’ve been much harder to find these problem sites. The next step is to do something about it.”

TTF is helping to educate the public about ways to reduce salt levels.

Other partners include The Nature Conservancy and its Stream Stewards Program, Pennypack Ecological Restoration Trust, Willistown Conservation Trust, and Penn State’s Master Watershed Steward Program.

The William Penn Foundation is funding the effort through its multimillion-dollar Delaware River Watershed Initiative that is supporting the Stroud Center and more than 50 other leading nonprofits working together to reduce threats to water quality for the 15 million people — more than 5% of the U.S. population — who get their drinking water from the Delaware River basin. The initiative targets eight subwatersheds, or clusters, that make up 25% of the basin and are of critical ecological value.

Jeff Chambers, a volunteer with The Nature Conservancy’s Stream Stewards Program, says, “In the years ahead, I believe those of us who care deeply about our environment will increasingly turn to organizations like the William Penn Foundation, Stroud Water Research Center, the National Park Service, and The Nature Conservancy to protect our natural resources. With their help and guidance, it will be us, the community scientists, who will become the stewards of our air, land, and water.”

What you can do:

- Donate to help fund our research and community science efforts.

- Read and share “Over-Seasoned: Our Taste for Salt is Killing Our Freshwater Ecosystems”

- Read and share “Winter road salt is making some Philly-area streams as salty as the ocean, enough to kill wildlife”

- Download and share the Save Our Streams From Road Salt flyer.

- Browse Monitor My Watershed to see monitoring data in your area.