Stroud Scientists at Work

Stroud Alum, Dave Arscott, Returns to Become its Assistant Director

Dave Arscott, who coordinated phase two of the vast New York drinking water project from 2003-2006, is coming back to the Stroud™ Water Research Center. After almost three years at the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research in New Zealand, Dave will return in February to serve as the Center’s assistant director.

“I am ecstatic about the return of Dave Arscott,” said Director Bern Sweeney. “He is a young, energetic, extremely bright scientist with a demonstrated ability to work both independently and in a team setting. He has terrific scientific credentials and a broad background, which will enable him to work with Stroud scientists as both a collaborator and team leader. Perhaps most importantly, he enjoys helping people, believes in our mission and, like the rest of us at the Center, is dedicated to understanding and conserving streams throughout the world.”

Dave will need all those attributes as he takes on the new position of assistant director, a position that requires a broad range of management, leadership and scientific skills. And “throughout the world” is an apt phrase for a man who got his Ph.D. at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology before professional stints here and in New Zealand.

We recently sat down (virtually) with Dave as he prepared to pack up his family for the 9,000-mile trip from Christchurch on the south island of New Zealand to Avondale, Pennsylvania and had this conversation with him.

First of all, welcome back.

Thanks. I’m excited to return to the Stroud Water Research Center and honored to be its assistant director.

What will your role be here?

I’ll assist Bern and the whole staff in the direction, coordination and oversight of scientific research projects and in the dissemination of our findings to the public through the Center’s varied outreach programs.

Specifically, I expect to spend half of my time working directly with Bern on issues ranging from coordinating research, education and public outreach programs, to meeting with members of our Board of Directors and overseeing operations at the Stroud Preserve and Maritza station in Costa Rica.

A significant portion of my time will be spent working with the scientific staff to prepare interdisciplinary projects, proposals and budgets, and in driving the external review of the Center’s research programs that was mandated by the Center’s strategic plan. And, happily, I’ll devote the remaining time to pursuing my own research interests.

What memories do you have of your time at Stroud Water Research Center?

I didn’t need to go as far as New Zealand to realize what a special place the Stroud Water Research Center is — and how its incredible people have made it so special. During my three years at the Center, I coordinated the project on New York City’s watersheds, which gave me the opportunity to interact at both scientific and personal levels with nearly all the Center’s staff. I’m still amazed at how smoothly the project operated — despite some major logistical and technical difficulties — and how well the collaborations worked among the different scientific disciplines.

And what of your own scientific interests? What have you been working on of late?

One of the things I loved about the Stroud Water Research Center was the central importance of collaborative work. So it’s exciting to me that several of my current projects are synergistic with the work of other Stroud scientists. In January 2008 I participated in an expedition to the McMurdo Ice Shelf in Antarctica to conduct field studies on the ecology and biogeochemistry of meltwater ponds as part of New Zealand’s Antarctic Ecology Program. That was an incredible experience, and as part of that work, I collaborated with other scientists including Anthony Aufdenkampe from the Stroud Water Research Center, to quantify carbon dynamics during the freezing cycle in several ice shelf ponds. I look forward to continuing that work.

In addition, I’m working with researchers from New Zealand, France, Germany, and Italy, on projects in the field of ecohydrology — or quantifying relationships between hydrological processes and biotic dynamics at the watershed level. My primary interest lies in understanding the ecological impact on river corridors caused by human-induced changes to the hydrological cycle — an issue that was a critical part of our work in the New York watersheds. In New Zealand, however, most of the funding for that stems from the contentious issue of water allocation — or how we can apportion water for human use in ways that minimize the degradation of ecological, cultural, recreational and aesthetic values.

Finally, I have worked in “biosecurity,” New Zealand’s invasive species ecology program, and in particular on the ecological effects of the invasive algae, Didymosphenia geminata. In New Zealand, this species achieves incredibly high biomass in certain rivers, which has resulted in significant ecological changes and a nationwide effort to control its distribution. Now the species is spreading across North America and has recently turned up in rivers in Virginia, Connecticut and New York. I plan to continue to study its impact while at the Center.

I hope to pursue all of these research themes, in addition to other collaborations envisioned by Stroud scientific staff, as my interests in stream ecology are broad and what I really enjoy most is working with others to achieve high-quality scientific outcomes.

You have traveled more than 18,000 miles from the Stroud Center to New Zealand’s National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research and back. How does it feel to be back?

I have been really fortunate in my career so far — three great years at the Stroud Water Research Center followed by two-and-a-half fascinating years in New Zealand. And now my family and I are excited to return to Pennsylvania and to reconnect with the Stroud community.

We have had an extraordinary experience and made wonderful friends on the other side of the earth. New Zealand is a special place, and we will miss the proximity to so many amazingly different environments within a short drive of Christchurch. The kids, Lewis (6) and Alyssa (4), have loved being so close to the ocean beaches where boogie boards, kayaks, sand castles and sea creatures are integral parts of our summer play times. And Yeda and I will miss the evenings spent steaming green-lipped mussels and paua (abalone) in garlic, herbs, butter and Parmesan.

We look forward to sharing our adventures with the friends we left behind in Pennsylvania and to starting exciting new work with my colleagues at the Stroud Water Research Center.

Under the Microscope: A Closer Look at Microbial Ecology and the Legacy of Tom Bott

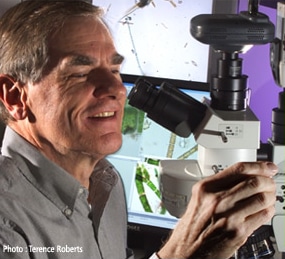

Spend a few minutes with Tom Bott, senior research scientist and Stroud™ Water Research Center vice president, and you’ll be itching to get behind a microscope to see just what it is that has captured his imagination — and continues to fascinate him after a long and remarkable career in microbial ecology.

Filling “The Big Black Box”

When he arrived at the Center four decades ago, says Bott, “The microbial ecology of White Clay Creek was just a ‘black box;’ we really didn’t know anything about it.” In fact, the entire field of microbial ecology was still a fledgling discipline.

To illustrate just how the science has progressed, Bott points to a recent issue of the journal, Applied and Environmental Microbiology, more than a thousand pages thick. “When I started in the field,” he says, tapping the huge tome, “one could actually read through much of this journal in a month; now that’s virtually impossible. Every issue is a testament to how much we’ve learned about something that is not even visible to the naked eye, yet is critical to the life of every stream.

“People were used to seeing and thinking about fish and insects,” he continued, “but not about all those organisms we can’t see without a microscope. We did something quite revolutionary; we started to view the microbial world as part of the ecosystem, and what we now know as a result is amazing.”

For it turns out that these microscopic organisms — the bacteria, algae, protozoa, fungi — are among the most active and important organisms in the stream ecosystem. In fact, billions of them may coexist in a square centimeter of streambed — an area about half the size of a thumbprint — and collectively they consume enormous amounts of biological material, which is essential to protecting the health of a stream.

But there is still so much more to learn about how these microbial communities interact with other organisms and their important contribution as the basis of the food web — a primary source of energy. These are the types of questions that continue to drive Bott’s research, even in his “retirement.”

A Look Back at Major Projects

Our work was critical to the advancement of aquatic ecology. And it was groundbreaking – no team of scientists had ever looked so comprehensively at the structure of a stream or at how streams actually function,” says Tom Bott, retiring senior research scientist and vice president, of his experience at the Stroud Water Research Center (shown here in 2000 with colleagues from the New York City drinking water project, from left to right: Chad Colburn, Bern Anderson, Denis Newbold, Charlie Dow, Tom Bott, Lara Martin and Dave Montgomery). Says Bott of his tenure here, “The work we’ve done over the decades has created a wonderful body of data — from which we continue to draw important scientific conclusions.” He is quick to point out that they never could have learned all they have without the benefit of studies over a long time and data from a broad array of streams — conditions that have been the bedrock of Stroud research. Bott and his colleagues have studied algae in dozens of streams and rivers, from White Clay Creek to the headwaters of the Amazon River, and some of their research projects have been ongoing for 30 years and more.

Such long-term research has been facilitated in the White Clay watershed by landowners who have put their land under conservation easements and restored much of the area’s streamside forests.

One important conclusion Bott and his team have drawn from their research is the link between land use and stream health. Noting that algal growth rates in the wooded reaches of White Clay Creek are consistent today with what they were 30-40 years ago, Bott says the message is clear: “If you manage your watershed, your stream will remain functionally healthy.”

Over the years Bott has also worked with industries to assess the effect of their effluents on algal growth in streams, the ways in which their products could affect microbial activity in aquatic systems, and ways that microbes could be used to reduce the impact of industrial products on water quality.

He is currently studying the effects of acid mine drainage (AMD) on algal growth, a problem that continues to impair thousands of stream miles in Pennsylvania and across the country decades after mining operations have shut down.

The Next Big Thing: Where We Go From Here

“For the most part, we’ve studied microorganisms and what they do as communities,” says Bott. ”But scientists have to date identified far fewer organisms than actually exist in our soils, in the water that passes through them, and in our streams, rivers and lakes. Techniques, such as genetic probing, will allow us to significantly refine our understanding of the microbial world, so the next tasks are to identify all these microbes — at least to genus — and to understand how they interact with their environments.”

As scientists learn more about the specific roles that each microbial population plays in a functioning stream ecosystem, they will gain a better understanding of how that ecosystem works. That knowledge is fundamental to our ability to protect, preserve and restore our sources of fresh water, and it has important implications not only for stream condition and water quality, but also for public health, aquaculture, and industrial practices.

Reflections

As this year will be marked by Bott’s retirement, he and the senior staff are in the process of finding his replacement.

“I feel very fortunate that I was given the opportunity to develop my career here,” says Bott with a wistfulness that is almost immediately replaced by the animation and excitement that come from the satisfaction he derives from his work — and from the 40 years he has spent at a place he loves.

Bott will continue to work at the Center on a part-time basis, a process of succession that will allow for a smooth transfer of knowledge, provide a continuity of research programs, and ensure the continuation of the Center’s pioneering research under his direction.

Stroud Educators at Work

Creating Citizen Scientists: A Collaboration with Cabrini College

With a grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF), Cabrini College and the Stroud™ Water Research Center are about to embark upon an innovative educational program to develop curricula with the ultimate goal of instilling in students the capacity and the aspiration to work as “citizen scientists” in their local watersheds and to disseminate the knowledge they gain to their peers and the community at large.

The Watershed Citizenship Learning Community Project

Designed for non-science majors, the two-part program will combine science with psychology and “applied democracy” — the empowering of citizens to make scientifically informed decisions that will affect their communities. Watershed science and watershed citizenship will be the themes around which Stroud educators and Cabrini College biology and psychology faculty members will create a new interdisciplinary and experiential learning program — one that will take their students into the Valley Creek watershed and the communities within it.

“We hope to use this new curriculum to engage students in the real-world issues of water quality and conservation, while also providing them with the scientific foundation and problem solving skills that will enable them to take action,” said Susan Gill, Stroud director of education. An added benefit is that the planned fieldwork will also bring tangible benefits to the communities of Valley Creek.

Focus on Valley Creek Watershed and the Crabby Creek Restoration

The Valley Creek watershed, which includes Radnor, Pennsylvania, the home of Cabrini College, has been subjected to extensive new development over the last two decades. “This is an important watershed and it developed very rapidly, without a coordinated storm water management program,” said Stroud senior research scientist, John Jackson.

As in other urban watersheds, its rapid population growth and development have increased the impervious surface area and contributed to increased flooding in the area — yet many residents still do not truly understand the impact of land use changes on stormwater runoff, flooding or water quality.

“The problem is that most residents we’ve surveyed, while conservation-oriented, are not aware of the storm runoff problem or the damage it has caused in their community,” says Dr. Missy Terlecki, who helped Cabrini students survey hundreds of residents of Crabby Creek in the Valley Creek watershed in preparation for this program, and who will co-teach the Watershed Citizenship course at Cabrini in the fall. “The results of the survey provided critical inputs that have helped us determine how we should move forward and shape this program.” Survey results demonstrate a real education problem and also a desire by community members to participate in the Crabby Creek Restoration Project. This curriculum provides a great platform to address both of these issues while providing students with a meaningful educational experience.

Collaboration with the Valley Creek Restoration Partnership will enable the students to engage directly with the community, and contribute to the restoration of the watershed — something Terlecki says will also give them the confidence and interest to take their stewardship skills with them wherever they live after graduation.

Technology in the Classroom

Cabrini College’s Watershed Ecology class, which will be taught jointly by Dr. David Dunbar and Dr. Caroline Nielsen, will give students the core concepts of watershed ecology and will include the implementation of basic water assessment techniques — from chemistry to macroinvertebrate monitoring. “But, what’s really powerful and exciting about the course,” says Dunbar “is the ability of our non-science students to perform state-of-the-art biology experiments — including DNA bar coding studies on the macroinvertebrates of Crabby Creek.” The idea of introducing this technology is not just to get accurate and comprehensive data, but to excite and inspire students with tools to which they wouldn’t normally get access.

Studies of Crabby Creek performed (as part of the Schuylkill River Project) by a team of Stroud scientists led by senior research scientist John Jackson will provide the baseline from which Dunbar’s students will compare their results and assess water quality.

A Win-Win Situation

Terlecki reports that the benefits of this kind of experiential learning are huge. “Seeing is believing,” she says. “There’s a much higher level of understanding when people experience something, rather than just read about it in a book.” Based on their initial experiences, students have underscored both how much they appreciate working with community members and their commitment to practicing certain conservancy behaviors as a result of this program.

“We think it’s a win-win situation for everyone involved,” says Dunbar. “If we’re successful, we’ll be sending our graduates out into the world as environmental advocates, with the confidence to believe they can make a difference — and the skills to do something about it.”

Kristen Travers, Stroud education programs manager and a key player in the formulation and evaluation of the course, put it this way. “This collaboration gives us the opportunity to simultaneously share the science of Stroud and to help mold watershed stewards. That’s definitely a win-win.”

Events

The Hot Ticket: Our 2nd Annual Wild and Scenic Environmental Film Festival

If you missed out last year — here’s your chance to join us for this year’s entertaining and inspiring line up of short, independent films and documentaries at our 2nd annual Wild and Scenic Environmental Film Festival on February 12th.

Presented nationally by Patagonia, Inc. and sponsored locally by outdoor gear purveyor, Trail Creek Outfitters, this collection of award-winning films underscores the need to protect our increasingly threatened natural resources, including, and most importantly, water.

“The roots of the festival dovetail nicely with our efforts to share our knowledge and put our science to work — engaging individuals in the simple practices that we know will protect and preserve our watersheds and our drinking water,” said Bern Sweeney, director of the Stroud™ Water Research Center. “We’re so fortunate to have a generous partner like Trail Creek Outfitters that shares our values and our commitment.”

“This year’s attendees will be treated to a series of documentaries, animations and short films that will take them to places they may never otherwise see, teach them something new — and, we hope, inspire them to get involved” said, Ed Camelli, Cofounder of Trail Creek Outfitters.

The history of the Wild and Scenic Environmental Film Festival itself offers us a great lesson in what can be accomplished by even a small group of concerned and motivated citizens. Almost a decade ago the South Yuba River Citizens League (SYRCL), a community group dedicated to preserving, protecting and restoring the Yuba Watershed — which stretches from its headwaters in the Sierras to California’s Central Valley — successfully added a 39-mile stretch of the South Yuba River to California’s Wild & Scenic River System. That accomplishment gave this stretch of river the protections of the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, which Congress passed in 1968 — and a status given to our own White Clay Creek in October 2004.

In its quest to raise awareness about the problems facing its watershed and the funds to address them, SYRCL also created the largest environmental film festival in the United States. Now in its seventh year, the Wild and Scenic Environmental Film Festival is a reminder that threats to our natural resources persist but through engagement and action, we can contribute to reversing the tide.

So, bring your family and your friends. We hope to see you there!

Outreach

The Gift of Fresh Water: A Mayfly Club Member’s Story

This holiday season was especially meaningful to Philip Dixon. A native of Chester County, Pennsylvania, Philip has spent the last six months living in Ecuador. As a teacher at a high school in the city of Guayaquil, his every day existence is starkly different from that of the impoverished villagers who live just a few kilometers away. So he and some friends decided to do something to make a difference.

Guayaquil is the largest and most populated city in Ecuador, with approximately two million inhabitants. The center of Ecuador’s manufacturing and fishing industries, Guayaquil sits on the banks of the Guayas River, which flows into the Pacific Ocean, carrying in its waters much of the city’s untreated waste. In the barrios of Guayaquil and the downstream villages, the residents routinely boil their water before washing, cooking or drinking.

Students at the Colegio Americana, where Philip teaches, are healthy and well fed, and he did not really comprehend the disparity between their lives and that of the residents in neighboring barrios and rural villages until he began his cycling tours of the area.

As a member of the Guayaquil cycling club, Cyclistas sin Fronteras (Cyclists without Frontiers), a group he joined shortly after his arrival in Ecuador at the suggestion of friend Arturo Stacy of Hot Bike in Urdessa, he now rides 20 or 30 kilometers outside of the city every weekend. “I see poverty around me every day in the streets of the city,” said Philip, “but this rural poverty was totally different. People use donkeys to transport their food and water, and they must boil the water they get from the river for drinking and cooking.”

As Philip describes the dusty dirt roads on which he and his friends cycle each weekend, he talks of dodging the chickens and goats, cattle and pigs that roam freely. And he notes that many of the tiny towns they ride through have limited plumbing and no sewage treatment. The residents rely on cisterns to catch water during the rainy season, and they have to carry that water to their often-distant homes. The towns, which depend primarily on subsistence farming, are little more than clusters of small shacks elevated on stilts to protect them from the short but extremely heavy rains that come between January and April and cause extensive flooding, particularly during El Niño years.

Members of the cycling club wanted to do something for the towns where they frequently ride. “The people living in the areas where we ride are extremely poor,” said cyclist Hiroshi Ozeki. “We thought it would be a good idea to give back to these communities by preparing sacks of food for each family.” In response to the club members’ enthusiasm, some of their employers decided to contribute, too. Flint Group, a printing supplies company, donated food, money — and the use of a delivery truck to the cause. And, food products company, Confoco International, also chipped in with a donation.

“We all met on a Thursday night to pack up 400 bags of dried milk, rice, tuna, lentils, and more,” said biker Rudolf Ringer. “It was a wonderful feeling. People lined up to receive the bags of food, but what really struck me was how the bottled water we distributed was met with such gratitude.”

An adventurer and outdoor enthusiast, Philip joined the biking club to experience the area and to create a community of friends with whom to enjoy his new life. What he didn’t expect was how large his community of friends would soon become – nor how much satisfaction it would give him. Said a teacher from the town of Frutilla, to Philip and his fellow bikers, “It means a lot to me that you are giving back to my community.” Now the villagers of the various pueblos in the coastal plain west of Guayaquil — from Frutilla to Buenosaires, and Sacahun to the Guayas Province — call him “Amigo.”

“I hope that my experience will help raise awareness for the challenges that these villagers face daily — as it’s a challenge shared by millions of poor around the world,” said Philip. “Though we often take it for granted, access to clean, fresh water is not a given.”

In the News

Do You Know What’s in Your Drinking Water?

One of several proud Willowdale Steeplechase beneficiaries, the Stroud Water Research Center is also the subject of special coverage in the spring issue of Chester County Town & Country Living magazine. The cover story by Colleen McLaughlin, with photos by Caitlin Bellucci, profiles each of the Willowdale beneficiaries and will be in stores on March 15th, 2009. Editor, Diana Cercone, was kind enough to give us a peak at the issue and share with us the Stroud story lead:

“Do you know what’s in your drinking water? Scientists at the Stroud Water Research Center, a non-profit research organization located in Avondale, dedicated themselves to answering this question long before our newly eco-conscious society made it fashionable to consider such things.…’We do both ivory tower science and practical science,’ explained Bern Sweeney, who has been with Stroud since 1972 and has held the positions of president and director since 1988.”

Want to read more? The magazine is sold by subscription and in area bookstores, including Barnes & Nobles and Borders, as well as selected specialty shops and markets. Complimentary copies of the spring issue with a special one-year subscription offer will be available at the Stroud Water Research Center’s March 11th event, The Power of Photography: An Evening with Bob Caputo.

Stroud Scientists and Educators Present

Disseminating Our Findings to Our Peers and the Public at Large

Our ability to disseminate our findings to a broad audience allows us to increase awareness and create a public dialogue centered on the protection, preservation and restoration of watersheds everywhere. It’s for that reason that our scientists and educators engage in both scientific and public forums to share their findings. The following highlights recent presentations.

USING POPULATION GENETICS TO AID FISHERIES MANAGEMENT

A Channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus), one of seven warm water fish species now under study at the Stroud Water Research Center.West Chester University’s Biology Department invited Willy Eldridge, research scientist and head of the molecular fish ecology department at the Stroud Water Research Center, to address its faculty and students on November 24th, 2008. Eldridge’s discussion focused on several issues, including how hatcheries can wisely use genetics to compare strains to determine the best parentage to stock, the evaluation of hatchery success in maintaining diversity in an endangered salmon species, and the negative impacts of past practices on wild coho salmon — a candidate for the endangered species list.

Eldridge will attend the Annual Meeting of the NY & PA Sections of the American Fisheries Society in Owego, NY from February 4th to 6th where he will present, Effect of rate of change during diel (24-hour) temperature fluctuations on growth, stress and pathology of seven warm water fish species.

ASSESSING WATER QUALITY IN LATIN AMERICA: PAST AND PRESENT APPROACHES

For Latin America, fresh water is no longer just a public health issue; it means big business. Many countries lack the regulation and sewage infrastructure to protect their watersheds and safeguard their water supplies. Addressing these problems is an essential step to ensure public health and continued income from increasingly important tourism and other industries. A business need has begun to drive the desire for greater understanding of how to best use and protect Latin American watersheds and capitalizing on that renewed interest was the catalyst for a January 27th meeting of several prominent environmental organizations hosted by Conservation International at their San Pedro, Costa Rica office with funding from Blue Moon Fund. The purpose of the meeting was to discuss water-related conservation issues in Costa Rica, and also the potential for using the Rio Sierpe system as a model project for an integrated approach to water, biodiversity and ecosystem service conservation management. In attendance were representatives from: Amigos de Osa, Asociación Centroamericana para la Economía, la Salud y el Ambiente (ACEPESA), Blue Moon Fund, Centro de Derecho Ambiental y de los Recursos Naturales (CEDARENA), Conservation International (CI), Earthwatch Institute, Nectandra Institute, Rainforest Alliance, University of Vermont, and Bern Sweeney, senior research scientist and director of the Stroud Water Research Center, who discussed past and present approaches to assessing water quality.

DIEL CYCLES OF ORGANIC MATTER IN WHITE CLAY CREEK

At the invitation of event cosponsors New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, United States Geological Survey (USGS), New Jersey Water Science Center and Rutgers University New Jersey Water Resources Research Institute, Stroud senior scientist Lou Kaplan presented to an audience of environmental scientists and government agency environmental and regulatory personnel in Trenton, New Jersey, on December 12th, 2008 at the event, Diel Cycling of Chemical Constituents of Organic Matter in Surface Waters and Related Media – Scientific and Regulatory Considerations. Kaplan’s presentation, Diel Cycles of Organic Matter in White Clay Creek, which he coauthored with Stroud scientists Anthony Aufdenkampe, Denis Newbold and Dave Richardson (now of the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies) highlights dramatic changes in dissolved and particulate organic matter (DOM, POM) concentrations and compositions in water samples taken over a 24-hour period from the White Clay Creek. The research on which his presentation was based points to the need to understand the causes for the fluctuations, as well as their implications for water quality monitoring — implications which include the actual amounts of DOM and POM in streams and rivers as well as their specific interactions with regulated substances, such as heavy metals and man-made organic chemicals.

FRESH WATER: CONNECTING COSTS AND CHALLENGES

Senior research scientist and director of Stroud Water Research Center, Bern Sweeney, was asked to a kick off workshop hosted by Chester County Water Forum on December 16th, 2008. The workshop entitled, Fresh Water: Connecting Costs and Challenges, was attended by Chester County commissioners, representatives from the USGS and the Water Resources Authority. Its purpose was to define and address the key issues related to the county’s ability to provide an adequate quantity of clean, fresh water to its citizens today and for future generations. Sweeney’s presentation, Clean Water Action: Improve, Conserve, Forget it, was designed to outline the primary issues prior to the breakout brainstorming sessions led by attendees. This comprehensive workshop went beyond discussions of science and infrastructure to equally critical issues, such as what can be done to create the incentives that will begin to engage the public in essential conservation measures at home. Chester County 2020 will be summarizing the results to share with state senate and congressional representatives.

TREES, STREAMS AND WATER QUALITY: THE CONNECTION

Senior research scientist, John Jackson addressed the White Clay Creek Watershed Management Committee on April 7th with data amassed from the Schuylkill River Basin over a 12-year study period, which outlines the links between land use and water quality.