By Scott Ensign and Diane Huskinson

Muddy Waters

Floating in motorboats above the waters of the Choptank and Pocomoke rivers in Maryland, science teams from Stroud Water Research Center are collecting data to understand what lurks beneath. Much like crime scene investigators, they are looking for DNA.

“Rivers carry dirt eroded from upstream watersheds and agriculture fields to estuaries, clouding coastal waters and threatening seagrass beds and oysters,” says Scott Ensign, Ph.D., research scientist and assistant director of the Stroud Center.

Too much dirt, or sediment, flowing into the bay buries oyster reefs in mass graves. Olivia Caretti, coastal restoration program manager for Oyster Recovery Partnership, says, “Besides smothering and killing oysters, the burial of reefs also reduces how much habitat is available for settling oyster larvae. If oyster larvae cannot attach to exposed, hard substrate, they won’t survive, reproduce, or be able to grow into healthy adults for harvest.”

This is a serious issue for the Chesapeake Bay, where 99% of the historic oyster population, which helps to filter pollutants and support marine life, has been lost. Oyster harvesting is also the fastest-growing aquaculture industry, creating thousands of jobs in the region and providing an important food source for people.

“Reducing how much sediment washes into the bay is an important step in sustaining our coastal resources and creating a healthier ecosystem,” says Caretti.

Matt Pluta, director of Riverkeeper programs for ShoreRivers, which is partnering with the Stroud Center to monitor the Choptank, says sediment pollution is an obvious threat. “It’s no surprise to anyone who’s ever been in the Choptank that the river’s waters are cloudy.”

Agriculture is a leading source of sediment pollution, but farmers are helping to change that. According to a 2021 report by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service, Maryland has the highest cover crop adoption rate of any state in the nation. However, Pluta points out that cover crops are a seasonal solution that relies on yearly government-funded financial incentives. Working with the Stroud Center and Assateague Coastal Trust, he hopes that by learning more about the movement of sediment, he can ultimately determine the return on investment cover crops offer for reducing sediment pollution compared to other more permanent solutions like streamside forests.

It is not yet known, says Ensign, how long it will take “for watershed erosion controls today to clear up muddy estuarine waters in the future. Creating a timescale that identifies sources and sinks for sediment is really complicated.” A key piece of that puzzle is first being able to track the movement of sediment.

“How fast sediment moves from an upstream source to an estuary — days, months, decades — depends on the size of the watershed, the type of river, and the type of coastline it feeds,” Ensign says.

DNA Doesn’t Lie

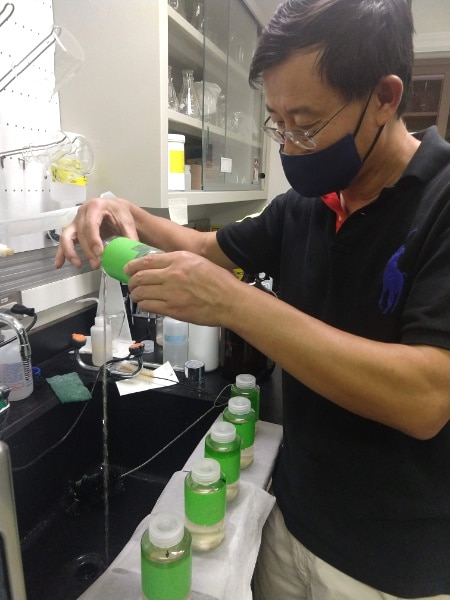

To track the sources and fate of sediment as it crosses from rivers into estuaries, and ultimately, to help predict when efforts to control erosion will pay dividends downstream, Ensign and freshwater microbiologist Jinjun Kan, Ph.D., are leading a research project funded by the National Science Foundation that uses new, and potentially cheaper, technology that tracks microbes attached to sediment particles using their DNA.

Ensign says, “When you fill a bucket with cloudy estuary water, you are looking at a mix of sediment that came from the watershed upstream sometime between last week and a thousand years ago. We want to find out how much of that sediment arrived during the most recent storm because that’s the timescale for matching specific pollution sources (and their solutions) with impacts to the bay. Each sediment particle in that bucket of water hosts bacteria, archaea, fungi, and other organisms that reflect where that particle was in the past week: the river, the estuary, and other stopping points in between. We use the DNA of all those organisms together to pinpoint a particle’s history.”

Kan explains further, “When we sample the DNA, we are collecting a kind of fingerprint, but instead of representing a single individual, this fingerprint reveals the genetic makeup of an entire community, and it’s the community that changes depending on its environment. Food sources, water chemistry, and temperature changes downstream, for example, can lead to changes in the community.”

A key part of applying this technique is understanding how slowly (or quickly) the community’s fingerprint changes as it enters a new environment, so the research team will use laboratory assays to simulate this changing environment in a controlled way and measure how the DNA fingerprint changes.

Empowering Students and Citizens

Partnerships with ShoreRivers and Assateague Coastal Trust will put the research findings into a broader perspective of river water quality. The two organizations, along with citizen science volunteers, will attend Stroud Center trainings to help them build and maintain EnviroDIY™ Monitoring Stations. The stations collect a variety of water quality data that will be visible in real time on Monitor My Watershed™, part of the WikiWatershed™ toolkit. ShoreRivers and the Stroud Center’s education department will work together to incorporate the data into K–12 education programs.

Take Action

- Not all of our work, tools, and equipment are covered by grants. Donate to help us advance knowledge and stewardship of fresh water.

- Citizen scientists play a crucial role in data collection and monitoring. Contact David Bressler and learn how you can become a citizen scientist.

- Check out WikiWatershed for tools to help you participate in freshwater stewardship.

- Streams love trees! Volunteer to help us plant them by contacting Jessica Provinski.

- Tell us what you love about your local waterway and what you’re doing to protect it on social media. Find us on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, @stroudcenter.