Stroud Scientists at Work

Under the Microscope: Introducing Jinjun Kan, Microbial Ecologist

650,000 years ago, the pressure released from a magma chamber beneath a supervolcano created a massive explosion that formed a physical depression known today as the Yellowstone Caldera in Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming. The stunningly beautiful, freshwater lake that sits on this caldera is home to some interesting microbes and the subject of exciting research by Jinjun Kan, the microbial ecologist who will join Stroud Water Research Center in the spring.

Yellowstone Lake: A Hotbed of Research

With the help of remotely operated vehicles (ROV) equipped with special cameras, Kan and fellow scientists from Montana State University are collecting water samples from the lake surface and floor, where hydrothermal vents regularly produce hot water with temperatures of 60-100 degrees Celsius (140-212 degrees Fahrenheit).

In this seemingly inhospitable environment, unique single-cell microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea, thrive despite explosions of hot fluid and the lake’s other unusual geological and geochemical features. Kan wants to know why.

“Using molecular techniques, we’re enhancing our understanding of microbial distribution patterns and how the microbes interact with their ambient environments,” says Kan. “What we learn will shed light on the genetic diversity, as well as the various functions of the biological community that are linked to the geochemical signatures of its environment, allowing us to explore new, potential functions for these microorganisms.”

Microbial Fuel Cells: A Green Source of Power?

To contrast this research with another project Kan is currently working on is an exercise that provides great insight into both the breadth of his interests and the depth of his skill set. Let’s fast forward to the future and the concept of Microbial Fuel Cells; that’s right, fuel cells that could be used to generate power. “While it may be a bit premature to talk about finding a green fuel source for lighting,” says Kan, “I’m very optimistic about the potential of this research.”

This is not science fiction. A lot of bacteria, including members of the genera Shewanella and Geobacter, are able to transport electrons to a solid metal surface. By using pure culture species, it has been demonstrated that bacterial cells generate power under anaerobic conditions provided with appropriate carbon sources (electron donors). Kan’s research has shown that bacterial communities enriched from different resources, such as sewage, freshwater and marine sediments, can provide higher power generation and better stability than pure culture bacteria, as well as the ability to use diverse carbon sources as food. Kan is studying the bacterial consortia enriched in fuel cells to understand and optimize the community composition required for reliable power production, something that has many potential applications.

Says Kan of this ‘enriched’ bacterial community, “We hypothesize that these bacteria will have the ability to work as a team, creating a self-sustaining ecosystem of sorts. If we’re successful, we could eliminate the need for power supplies in certain devices, and the power generated by these organisms would be sufficient to operate such things as remote sensors.” That idea excites him tremendously, as the distant placement of these devices makes them extremely difficult to maintain. Monitoring and replacing failed batteries when a device is planted deep underwater, for example, can be a challenge. This new, green fuel source could potentially enable him and his colleagues to build more reliable scientific tools to monitor environmental data in remote areas, something that Kan believes will happen soon.

Getting Rid of Heavy Metal

When Kan talks about heavy metal, he’s not referencing his taste in music. He’s sharing his excitement about the potential to induce and enrich a bacterial community to help remove the toxic byproducts of industrial activities — such as copper, lead, and zinc — that are deposited in marine sediments.

Working with the scientists at the Space and Naval Warfare Systems Command (SPAWAR System Center, Pacific), a Navy research branch in San Diego, California, Kan is evaluating the impact of alterations to sediment on water quality and ecotoxicity. In other words, Kan’s research will determine how these changes affect the ecosystem — from the structure of the microbial community to the ambient environment in which they live.

Organic additions like acetate and chitin, for example, stimulate microbial growth and reshape the species composition of the microbial community. Kan’s work has shown that by adding heavy metals to sediment instead, important bacterial groups — including sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) and sulfide-producing/metal-reducing bacteria — are transformed, stabilizing the heavy metals, and enabling their sequestration in marine sediments.

No Stranger to the Chesapeake

A native of Shandong, China, and current resident of Los Angeles, California, Kan is no stranger to the largest estuary in the U.S., the Chesapeake Bay. He conducted his doctoral research in Environmental Microbiology at the University of Maryland, College Park, where his research focused on determining the kinds of bacteria that live in the Bay, as well as their distributions, population dynamics, and functions within the estuarine ecosystem. He’s excited to return to the area.

Says Tom Bott, the senior research scientist and head of the Microbial Ecology group whose retirement in 2009 catalyzed the search for a candidate with Kan’s qualifications, “The field of microbial ecology has been revolutionized over the past two decades by the application of molecular techniques to identify microorganisms in complex natural communities, even when we cannot culture those organisms in the lab. Jinjun has expertise in this area and his research here will deepen our understanding of microbial functions in streams because he’ll be able to link a particular function with the organisms that are actually doing the work. This is exciting in and of itself, but it could also open up innovative ways to leverage the capabilities of these microbes in solving environmental problems.

“There’s nothing like seeing microorganisms functioning at the extremes of life in a place such as Yellowstone,” Bott adds. “Both Jinjun and I did our post-doctoral work there before joining Stroud Water Research Center.” With a wry smile he adds, “I’ll say nothing more about the 40-year gap in the years we worked there!”

Bott will work with Kan on a transitional basis throughout 2010.

Stroud Educators at Work

The Whole River: Dividing a River into Parts, Claiming It for Economic Use, Ignoring Its Natural Community, We Lose Sight of the River Itself

Authored by Jamie Blaine, The Whole River was published in the Winter 2010 issue of Waterkeeper magazine.

Rivers around the world no longer run regularly to the sea. The Colorado stopped doing so in 1960, and China’s Yellow River runs dry for two-thirds of the year. More than half the world’s rivers are seriously depleted and polluted. The Ganges is befouled almost from its source, while the Volga annually transports 42 million tons of toxic waste to the Caspian Sea.

Despite all humankind’s spectacular engineering feats, over a billion people around the world lack access to safe drinking water — and three times that number suffer from inadequate sanitation. Diarrhea kills an estimated 2.6 million people each year, the majority of them infants and children. Two hundred million people suffer from schistosomiasis, an infection caused by drinking contaminated river water, and more than six million Africans have river blindness.

In place of the multi-faceted relationships people historically had with rivers, we have substituted a single determinant of their value: What can this river do for me? In our drive for economic growth, we have bent rivers to the human will. Across the globe, there are now more than 50,000 large dams, which collectively have displaced 40 to 80 million people. From Louisiana’s Atchafalaya River to China’s Yangtze, we continue to impose ever-bigger engineering solutions on natural wonders we do not understand and have ceased to care much about. Nor are we safe from these solutions: In 1975, a dam in China collapsed, and as many as 230,000 people died.

Rivers have provided us with immeasurable benefits. But we are destroying them, and in doing so, we are imperiling our future. We need to step back from the brink and reconnect with our rivers. We need to understand them, not simply try to control them — to appreciate the whole of a river, not just those parts we find useful, to realize that a river is not merely a channel through which we can push water and waste, but a natural system of which we are a part. We urgently need to awaken to the beauty of our rivers, and to see clearly the forces that threaten them.

Rivers in History

Streams and rivers provide the essentials of life – water and food. For humans, they have done much more. We have used rivers to bathe our bodies, wash our clothes, and remove our waste. Rivers have irrigated our farmlands and carried in their waters the fertile sediments that create and replenish the soil itself. Rivers have made possible the inexpensive and efficient transportation of goods — and thus the social, cultural and intellectual exchanges that have spurred the development of ideas and the spread of knowledge. Harnessing the flow and capturing the power of rivers was the source of the Industrial Revolution and the modern world as we know it.

The earliest civilizations grew on rich alluvial plains that rivers created, and to a great extent, rivers defined those early communities. People venerated their rivers as the source of life. Their earliest gods were river gods. But rivers could also be arbitrary forces of destruction, and people were often at their mercy, as floods obliterated their homes, droughts withered their crops, and contaminants poisoned their water. The river brought death as well as life.

Over time, people learned a great deal about stream and river ecosystems by dividing knowledge into distinct disciplines. In recent years, however, despite all we have gained through specialization, we have lost sight of the river itself. To see it again in its wholeness, we must learn to weave the separate threads of knowledge and experience into a single tapestry, honoring the uniqueness of each thread and understanding how together they constitute the whole river.

Let us look at three threads: science, utility, beauty. By observing the specific and often microscopic features of a river, scientists have sought to know it directly and tangibly. Particularly over the past 60 years, scientific research has vastly expanded our understanding of rivers and their ecosystems — their hydrology and chemistry, their physical properties, and their biological communities. Yet perhaps the most profound result of this work has been to demonstrate empirically what people understood intuitively for millennia — that a stream is a dynamic system whose equilibrium depends on constant change, that it does not flow in a vacuum but is an integral part of the landscape it drains, that what happens throughout a river’s watershed determines the health of the stream, and that upstream activities determine downstream health. No part of the river’s ecosystem — not even a single organism — can be completely understood except in its relation to everything else.

Human activity is the single greatest threat to the rivers we depend on. To understand the whole river is to account, in full measure, for the manifold benefits that rivers provide humans, and the true costs of doing so. Our dependence on rivers is not going to change. We cannot stop drinking their waters, nor eating the food they provide. We will continue to demand the power they generate, the transportation they make possible, and the recreation they support. But we must stop reducing streams and rivers to their utilitarian functions and calculating their value solely in economic terms. It is both an environmental and an economic imperative to restore their place in the natural world so that they can both regenerate themselves and continue to provide their unique array of benefits and resources.

The third dimension of the whole river is the one we have most thoroughly forgotten. That is to honor their natural mystery and beauty, which lie beyond the reach of scientific investigation and are too often the victims of economic exploitation. As with science, beauty is rooted in the particular — the play of light on the water, the caddisfly in its tiny case, the murmur of water flowing over stones, the scent of riparian plants in the early spring. It leads us to enjoy the stream directly, as we walk along its banks, raft into its reaches and fish its pools, feeling at these moments the solace of solitude and the paradoxical sense that we are not alone. We learn from these experiences that a stream is not just a collection of resources for us to exploit, but a community of which we are members. Beauty pulls us out of our individual selves and joins us with a world of immeasurable – and infinitesimal – things.

Science. Utility. Beauty. These are the building blocks of a vision of the Whole River. We need science to understand the structure of freshwater ecosystems, how they function in their natural states, and how human activity affects them. We need to be clear about the benefits we derive from streams and rivers and about the costs of these services. And we must reach beyond scientific data and economic value to allow our rivers to carry us on currents of wonder and connect us to the cosmos.

Protecting and Restoring Rivers: The Tragedy of the Commons Revisited

There is no clear and widely accepted set of rules governing the control, use, and stewardship of flowing water. In the United States, for example, nobody owns the rivers. Legally, all navigable waterways are recognized as commons, and belong to the public, held in trust by the states for the benefit of all. Yet the nation’s history, particularly in the West, reveals endless and frequently violent conflicts over water rights, and all too often the fact that rivers are not owned by anyone means that no one takes responsibility for them. They have become the classic manifestation of what ecologist and author Garrett Hardin called “the tragedy of the commons.”

Hardin described two uses of the commons: “a food basket,” from which people take things they need, and “a cesspool,” into which people put things they don’t want. Rivers have long been both. People take what they need from rivers and flush back into them what they do not want. But they do not stop there: They actually take the commons itself — as they remove in ever-increasing quantities the river’s water.

Because the evidence of stream and river pollution is often either buried in sediment or exported downstream, and because private water interests have wielded such enormous clout in this country, it has proved difficult for governments to assign responsibility and to enforce remediation. This is not simply a legal matter; it is a testament to ignorance. The misuse of rivers represents a profound misunderstanding of how they work — for they are far more than transport systems for waste. They are homes to communities of tiny organisms that perform the gargantuan work of breaking down and recycling that waste. Rivers, if we treat them with care, will, in fact, clean their own waters, and they will do so free of charge. If we continue to overload them with pollutants, however, we will kill them.

This is particularly true of small streams, which are a river’s lifeblood, the cradle of its biodiversity, and the home of billions of species that are the source of its energy. They are the places where land and water interact most closely and, because they are especially vulnerable to changes in land use, they are the key to a river’s health — and to the health of the human settlements that depend on the river. Yet, these small, often intermittent, streams, which make up 80 percent of most river systems, are the most neglected and least protected parts of the river’s ecosystem. And the human victims of that neglect are disproportionately the most vulnerable and least visible members of society.

Because all living things depend on clean fresh water, its distribution must be grounded in equity. Nobody can own the water, just as nobody can own the air; its benefits must flow to all people. While this is a matter of simple justice, implementing it is anything but simple in a world of unending and competing demands for resources. Any distribution system, moreover, must ensure the health of all living things, for it is neither ethical nor wise — nor, in the end, possible — to appropriate water for human use without regard for the environment that supports us all.

In a 1972 article “Should Trees Have Standing?” Christopher Stone argued that nature is not made up of “objects for man to conquer and master and use,” but is a subject with legal rights. His thesis was more than a call to give nature standing in courts of law. It was a demand that we transform the relationship of humans and the ecosystem from one of domination and exploitation to one of interdependence and community.

In our single-minded focus on what rivers can do for us, we have ceased to consider what we must do for them. In the name of progress, we have auctioned off the commons to those who would most aggressively exploit its resources. We have lost sight of the reality that a river can only belong to all of us when it belongs to none of us.

Just as Aldo Leopold urged 60 years ago that we “think like a mountain,” the time has come to think like a river — to understand that a river and its watershed is a natural community of which each of us is a member, a community that is crucial to our physical survival and to our yearning for transcendence, a community that we must learn to nurture once again so that it will continue to nurture us.

How To Create Carbon Neutral Landscapes: The New, Green Esthetic

This year Longwood Gardens in Kennett Square, Pennsylvania will greet nearly 800,000 visitors, each of whom will walk its grounds and take in the views that have made the botanical gardens a destination for travelers from around the world.

Longwood’s access to such a large audience with an expressed interest in landscape esthetics and horticulture is exactly what made collaborating with them a no-brainer for Stroud Center scientists and educators who wish to highlight the environmental benefits of best management practices for landscaping while simultaneously reshaping the public’s visual aesthetic to align with more carbon neutral choices.

Your Livable Landscape: Cultivating an Ecosystem Esthetic, a joint program funded by the National Science Foundation, will allow the two organizations to focus on teaching the public about landscaping techniques that produce a smaller carbon footprint. Central among the techniques will be those that reduce rainwater runoff, which mobilizes carbon and returns it to the atmosphere as CO2, a greenhouse gas that contributes to global climate change.

The Art of Changing Behavior

“Just giving people a good reason to do something doesn’t typically change a negative behavior all by itself,” says Susan Gill, Director of Education for the Stroud Water Research Center. “We’ve got to demonstrate that the new, desired behavior is both achievable and, in this case, also beautiful.” What better place to showcase that behavior in practice than at Longwood Gardens, a place synonymous with beautiful landscapes and widely respected for its horticultural education programs?

For years Longwood Gardens has utilized integrated pest management, constructed wetlands to increase water infiltration, planted meadows with native wildflowers to reduce water use, and practiced ecologically sound forestry methods.

Tom Brightman, Land Steward for Longwood Gardens, sees the collaboration with the Stroud Water Research Center as a wonderful opportunity to share these practices, which mirror “This view illustrates just one example of the beautiful tapestry of patterns we can create in more natural landscapes,” says Susan Gill, director of Education for the Stroud Water Research Center. “I’m looking forward to showing people that what is beautiful can also be good for the environment.”Longwood’s core values, with guests. “Although we’ve shared some of these methods with our visitors in the past,” he says, “this new program will model and highlight a few simple and effective behaviors at a time when so many people are interested in adopting sustainable practices.”

Brightman noted that, while Longwood Gardens has adopted sustainable practices for years, it is constantly seeking to implement the newest, most innovative and most effective methods. Better incorporating rainwater and runoff from impervious surfaces into the landscape is a strategic goal of the organization, and it helps advance Longwood’s long-standing commitment to conservation and sustainable practices.

The Your Livable Landscape: Cultivating an Ecosystem Esthetic program will include the development of new interpretive materials for use at Longwood Gardens and a video library for visitors, students and professionals, intended to demonstrate the “how-tos” of best practices. Finally, a series of public lectures slated for 2012 and a newsletter will provide a wider audience with access to knowledge and tips about carbon-neutral landscaping.

Outreach

The Stroud Memorial Lecture Series To Present Wade Davis, National Geographic Explorer in Residence

“I remember one time in college, one of those classic moments we all went through, sitting around with a group of friends, everyone in quiet desperation trying to figure out and suggest what they were going to become in life,” said Wade Davis as he reminisced about his years at Harvard University. “It was simply inconceivable to me that you could find a single slot into which to plug an entire existence.”

His thinking, so counter to that of his peers who followed far more traditional and predictable career paths, is exactly what has allowed Davis to live an enviably rich and rewarding life. Davis is driven by the philosophy that the canvas of one’s life is created by serendipity, and if you let it, destiny will find you. He capitalizes on this theory by saying, “yes” to every new experience and opportunity. The result: a prolific and productive life worthy of a novel.

This former logger and white water river guide, anthropologist and botanist, filmmaker and photographer, is also an author with many books to his credit, including One River, The Serpent and the Rainbow, Grand Canyon Adventure, and The Wayfinders: Why Ancient Wisdom Matters in a Modern World.

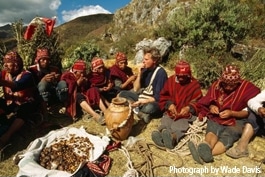

An advocate for the environment, Davis’ profound respect for nature is largely grounded in a worldview shaped by extensive experience living with indigenous cultures all over the world whose reverence for the sacred in their own geographies dictates a more harmonious relationship with nature. The stunning achievements of these ancient cultures demonstrate that there are other ways of orienting to place, landscape and home — and that reciprocity with the land is indeed, a rich and more sustainable approach. This theme is central to his book, The Wayfinders, and will be the subject of the upcoming Stroud Memorial Lecture on April 15th.

Davis shared with us his thoughts on several subjects, excerpts from which follow.

On Mentors and Influence

Despite extensive travels outside the Canadian province of his youth, his meetings with great shamans and even the Dalai Lama, when asked about those who have influenced him most, his mentors, Davis responds with a list much closer to home. A pivotal figure in his life, he says, was his father, of whom he speaks with great respect and gratitude, for this is the man who allowed his son all the opportunities he was denied, and who delighted in the education and success that could have placed a great distance between them. Speaking of his parents, he says the following:

The full measure of their generosity was their willingness to accept that they would not necessarily be the ones to guide my life. My father was especially understanding and kind. I think at some level he understood that he was unable to provide all that I needed, and he was never anything but delighted to know that I had found guidance in other mentors. It was as if he understood from the start that there was only so much he could teach me.

Another almost paternal figure in his life was Professor Richard Schultes, the renowned ethnobotanist from Harvard University. Davis remembers Shultes with great admiration and affection, for this was the individual who played the central role in what would become a several year research project and the subject of the best-selling book, One River. Clearly, their feelings for one another were reciprocal.

For Schultes, the book itself, took on a sort of magical reality. In his last years, according to his wife Dorothy, he kept the book on his bedside table, and when he could not sleep at night, he would open it randomly and read of his life. Not long before he died, he took me aside and, pointing to some dialogue in the text, said, “Did I ever tell you what Mrs. Bedard said to me when I first met her in 1943? Look, it’s right here!” I found this both amusing and very touching. Here, after all, was the man who had made my life possible. Now the book had become his life. His life had become my imagination, and my imagination had breathed meaning and content back into the life of an old man who was slowly fading away, as all old men must inevitably do.

On Canada and Threats to Its Sacred Geography

Through his writing, Davis hopes to influence the fate of three of Canada’s most important salmon rivers now threatened by a culture that, at times, favors industry at the expense of our environment, or what he calls “the industrialization of the wild.”

Against the wishes of all First Nations, the government of British Columbia has opened the Sacred Headwaters, a rugged knot of mountains in the Cassiar where by a miracle of geography are born within very close proximity three of Canada’s most important salmon rivers, the Stikine, Skeena and Nass, to industrial exploitation. Unless these initiatives are curtailed the very meadows and mountains that give birth to the Stikine, Skeena, Iskut and Nass rivers, as well as the Finlay, headwaters of the MacKenzie, will be destroyed, marred forever by an open pit copper and gold mine, an anthracite coal mine and an extensive network of wells and roads installed for the extraction of coal bed methane gas. Consider for a moment what this implies and what it tells us about our culture.

We accept it as normal that people who have never been on the land, who have no stories, who have experienced neither pain nor joy in these valleys, who have never felt the winds of winter or the promise of spring, may legally secure the right to come in and by the very nature of their enterprises leave in their wake a cultural and physical landscape utterly transformed and desecrated.

The cost of destroying a natural asset, or its inherent worth if left intact, has no place in the economic calculations that support the industrialization of the wild.

On the Planet’s Loss of Cultural Diversity

Davis is an expert on that small percentage of peoples that make up the largest percent of the world’s cultural diversity. He’s on a mission to slow the pace at which these cultures are vanishing. Each fortnight an elder dies — and with that event, there is also the loss of a language, a history, the myths, and infinite wisdom of a culture.

By nature of their remoteness, because they are foreign to us, and due to their diminished numbers, these dying populations have been dismissed and forgotten, and their amazing accomplishments all but ignored. Davis has become, among others, their spokesperson, celebrating all that comprises these cultures in hopes that we too will come to understand the value of their contributions, and incorporate them into our thinking about our place on this earth.

“Distinct worldviews yield profoundly different environmental outcomes,” says Davis. “Without doubt the depth and character of our creativity as a culture will be measured by our ability to transform our way of thinking, the values by which we interact with the natural world.”

It’s a Wrap: Recapping Our 3rd Annual Wild and Scenic Environmental Film Festival

From a corn field in Iowa to the dead zone that is now the Gulf of Mexico, two young men traded their combine for a canoe and embarked on a journey, to trace the environmental impact of the agricultural practices of our industrial food system. They share what they learned in Big River, just one of the 12 independent films and documentaries shown at this year’s Wild and Scenic Environmental Film Festival on February 11th.

The festival, named for the victory of a small, but determined, watershed advocacy group to secure Wild and Scenic protective status for a 39-mile stretch of the South Yuba River in California, has become a favorite local event, and an inspiration to many.

The Stroud Water Research Center is one of more than 90 environmental organizations that will host the festival this year. The Wild and Scenic On Tour manager, Susie Sutphin, an employee of the South Yuba River Citizens League (SYRCL), the festival founder, explains its success as the largest film festival of its kind in the U.S. “Its power comes from the incredible breadth of independently produced environmental films and their ability to inform, inspire, and empower people to act. The films” she continues, “take our environmental problems out of the abstract and into real life, but they leave the viewer with the sense that he can make a difference.” And indeed, the success of SYRCL and the growth of this festival are testament to the power of the individual and the community to make positive change happen.

“It’s a wonderful platform for us to convey how water is at the heart of so many environmental issues,” said Bern Sweeney, director of the Stroud Water Research Center. “And, it gives us an opportunity to show how a lot of small, individual acts of conservation can, in fact, make a big difference.” The festival’s message: we face many environmental problems, but it’s within our power to address them — and here are some people who are doing just that. Why not join them?

The Delaware Museum of Natural History provided an apt setting in which to stage this year’s screening. “Being surrounded by the creatures who share this earth with us was a fitting reminder of why it’s so important to protect our wild spaces and the natural resources, like fresh water, that sustain us,” said Liz Brooking, Director of Communications and Marketing for the Stroud Water Research Center.

Sponsors Committed to Preserving Our Environment

“As outdoor enthusiasts, protecting the environment is in our DNA so, it’s with great anticipation that we look forward to sponsoring this festival each year and supporting the freshwater research programs of the Stroud Water Research Center,” said Ed Camelli, cofounder of Trail Creek Outfitters, the lead sponsor of the event.

Trail Creek Outfitters was joined by locally owned culinary treasure, Talula’s Table, which provided the sustainably produced hors d’oeuvres, sandwiches, and sweets that tempted film goers. Paradocx Vineyards of Landenberg, PA, generously supplied the wines to complement the amazing spread of food.

The national sponsors of the festival are in the vanguard of companies that demonstrate that their commitment to the environment is not just “green washing.” For example, the personal care products company, Tom’s of Maine, is an avid supporter of those who work to improve water quality in their communities. Its belief that a supply of clean water positively impacts community health, business, recreation opportunities and overall quality of life, have prompted the company to donate $1 million to support American Rivers, River Network and other grassroots efforts.

Sierra Nevada Brewing Company works to support its barley growers’ sustainable farming practices and purchases more organic hops than any other brewer, helping to reduce the amount of pesticides and fertilizers that enter our fresh water. Clif Bar & Company supports the Organic Farming Research Fund and uses organic products to make its energy bars and to save our rivers from harmful pollutants.

Patagonia’s efforts to reduce its environmental footprint are legendary. Its pioneering work in the use of organic cotton and chlorine-free Marion wool are two of its many initiatives that have helped to protect our waterways from harmful chemicals. In addition, the company donates 1% of its sales to environmental organizations working to protect our natural spaces, including rivers and the forests that are vital to their health.

Osprey Packs of Colorado used its 2007 building expansion as vehicle for conveying its commitment to conservation. Its waterless urinals save an estimated 19,000 gallons of water a year in a region where water is an increasingly scarce resource. We salute the efforts of each of these sponsors and thank them all for their ongoing support and commitment to protecting our natural resources.

Until next year, it’s a wrap.

In the News

Leaf Pack: Breaking New Ground by Studying Bugs

David C. Richardson writes in the professional journal Stormwater magazine about Forest Grove Community School in Oregon and Mahopac High School in New York, two of the schools that are using the Leaf Pack Experiment and getting results that are making a real difference to their communities.

Well Water Contamination by a Gasoline Additive

Stroud Water Research Center scientist Anthony Aufdenkampe describes how the insidious chemical, methyl tertiary butyl ether or MTBE, which is added to gasoline to reduce knocking, is leaching into our groundwater and how it may remain there for centuries, in an article published by the American Water Works Association in November. The subject of a lawsuit and a verdict against gas company Exxon Mobil, MTBE has contaminated well water in the New York borough of Queens, and there may be many more cases like this across the country.

Drilling for Natural Gas Jeopardizes Clean Water

Journalist Leah Zerbe of Rodale News reports on the process of natural gas fracking and asks Stroud Center scientist Lou Kaplan for information on the potential hazards to our limited supply of drinking water, due to the consumptive nature of the process and the variety of chemicals involved.

“Anytime that we consider something like mining for coal or drilling for gas, all of those processes need to be viewed through a lens of environmental protection and sustainability,” says Lou Kaplan, senior scientist at the Stroud Water Research Center, of the pursuit of natural gas in the Marcellus Shale and in many parts of the western United States.

Stroud Scientists and Educators Present

Disseminating Our Findings to Our Peers and the Public at Large

Our ability to disseminate our findings to a broad audience allows us to increase awareness and create a public dialogue centered on the protection, preservation and restoration of watersheds everywhere. It’s for that reason that our scientists and educators engage in both scientific and public forums to share their findings. The following highlights recent presentations.

Addressing Public Health Issues at the Source

Says Bern Sweeney director of the Stroud Water Research Center of our environmental problems, “People do want to be part of the solution but they just don’t always know how; together we can change that.” Bern Sweeney, director of the Stroud Water Research Center, recently joined an all staff meeting at the Chester County Health Department to present Water Quality and Public Health Issues in the Mid-Atlantic Region: An Ecologist’s Perspective. Sweeney set the tone for his audience by underscoring how many water related health issues begin at the factory, the farm, and in our own households. He went on to convey that many of these issues can be avoided by employing best management practices (BMPs) at the source.

The health department, Sweeney argued, is essentially at the front lines in the battle for water quality and in a great position to connect the dots between our actions and water quality — potentially stopping some of those problems before they get started.

A good time to convey BMPs to a homeowner, he stated as an example, is during the installation and inspection of a septic system. Water conservation in the home can go a long way to ensure better functioning of a septic tank or any wastewater treatment system. So, Sweeney explained, going beyond general maintenance and pumping schedules to explain to the owner just how the system works, what chemicals to avoid, and what can overload the system causing poorly treated sewage to enter our water supply would be a great start.

The Use of DNA Barcoding in Water Analysis

Mexico City was the site of the Third International Barcode of Life (IBOL) Conference on November 9-13, 2009 where scientists from around the globe gathered to learn about the latest developments and join in the global initiative to identify, codify and create a library of the world’s species using DNA barcoding. Bern Sweeney, director of the Stroud Water Research Center and coleader of IBOL’s Freshwater Surveillance Group, presented the keynote, Water quality analysis with macroinvertebrate barcoding. Sweeney discussed how DNA barcoding will greatly enhance water quality monitoring efforts by leveraging both the inherent benefits of rapid data collection and analysis, as well as the vastly increased data set it delivers which can’t be obtained through visual identification alone.

Harvesting Rainwater

Throughout the world rainwater capture is a common strategy to supply water requirements for human use, including potable drinking water. However, in the United States, rainwater is permitted only for non-potable human uses. This is due to a lack of research documenting the feasibility of collecting and treating rainwater to meet regulatory standards suitable for protecting the health and well being of the public. In an effort to promote smarter and more efficient water use throughout the region, Bern Sweeney, director of the Stroud Water Research Center, made a presentation regarding rainwater reuse at a meeting involving the US Environmental Protection Agency Region III’s State Water Directors in Newark, DE last November. Sweeney’s presentation was entitled Rainwater Capture and Re-Use as Potable Drinking Water: A Proof of Concept Study.

Water Where You Want It

Stroud Water Research Center educator, Vivian Williams, presented Water Where You Want It, a lecture designed to underscore the link between forests and good water quality and outline tactics that homeowners can employ to prevent the problems associated with rainwater runoff. Williams addressed audiences at the annual meeting of the North Branch Neshaminy Watershed Association in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, in January, and as part of Bucks County Conservation District’s Citizen Scientist series last fall.

The five-week “Citizen Scientist Training Program: Pay it Forward in Your Watershed” project, was developed to educate homeowners living along streams and creeks about best practices for watershed stewardship; it focused on how to maintain riparian areas for the health of the waterway.

Streamside Forest Buffers Preserving Water Quality

Bern Sweeney, director of the Stroud Water Research Center, tells GreenTrek Networks about best management practices (BMPs) that reduce or prevent rainwater runoff, including streamside forests, and how programs are available to assist landowners in planting them.

Says Sweeney, “The science is now clear, that the widespread implementation of streamside forest buffers is one of the simplest, most cost-effective approaches to eliminating many of the problems in the Chesapeake Bay.”