Why Freshwater Ecosystem Restoration Often Fails to Meet Water Quality Objectives

After more than 50 years of the Clean Water Act and 86 years of the Pennsylvania Clean Streams Law, the United States and Pennsylvania have reached some major milestones in water quality improvements. These laws have reduced extreme cases of pollution, such as rivers catching on fire or streams changing color due to industrial waste.

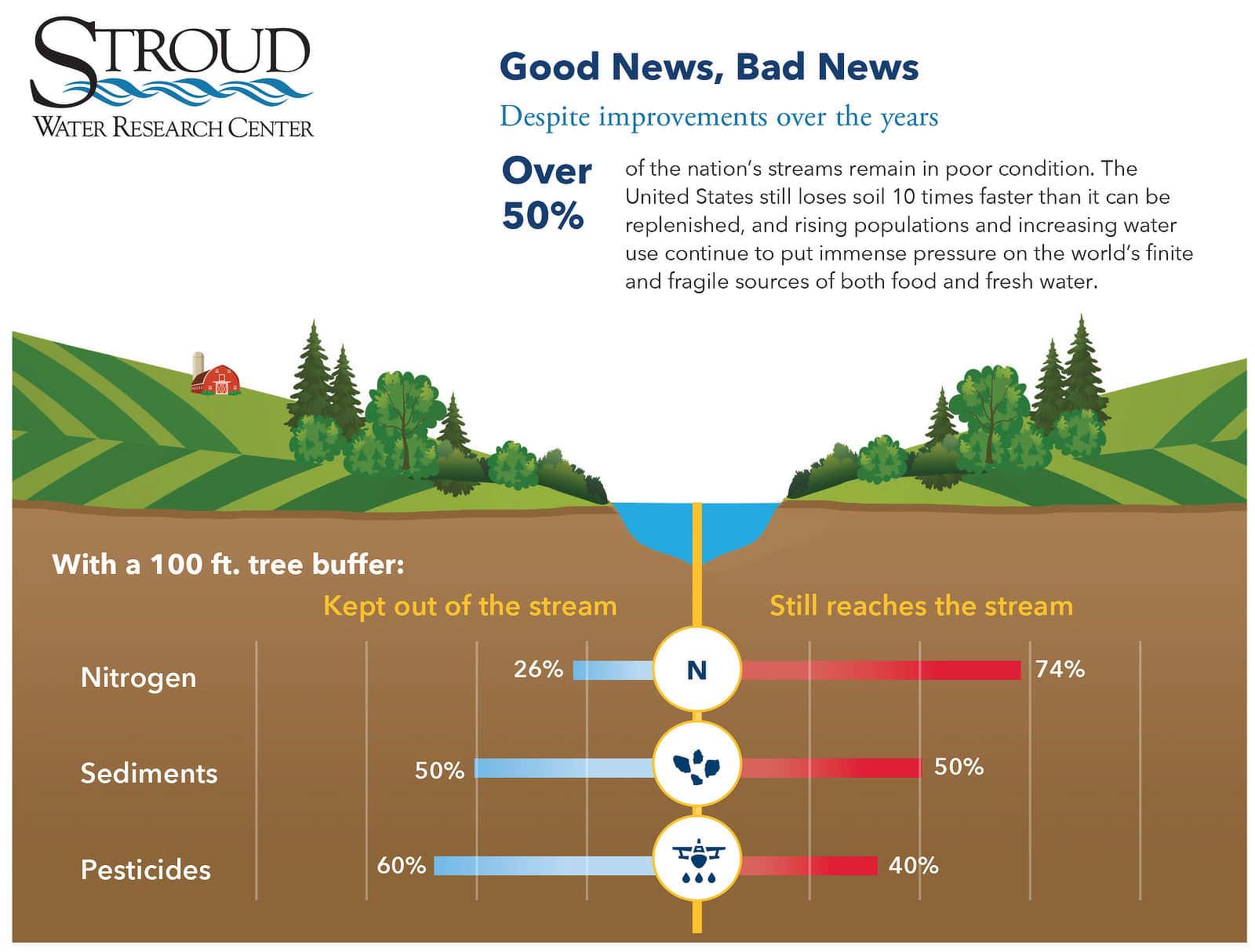

However, despite this progress and decades of significant investments, half of U.S. rivers and streams do not meet standards for fishing, swimming, or drinking.

In a webinar hosted by the New England Interstate Water Pollution Control Commission, Stroud Water Research Center’s John Jackson, Ph.D., and Matt Ehrhart examined why.

Since the webinar, Jackson, senior research scientist, and Ehrhart, director of watershed restoration, have addressed hundreds of individuals, many of them working for federal and state agencies to protect fresh water, about this issue.

What Is a Healthy Stream?

To help stakeholders understand why restoration efforts have fallen short, Jackson and Ehrhart first ask them, “What is a healthy stream?”

Jackson, the Stroud Center’s leading expert on freshwater insects, crayfish, snails, and other macroinvertebrates, says,

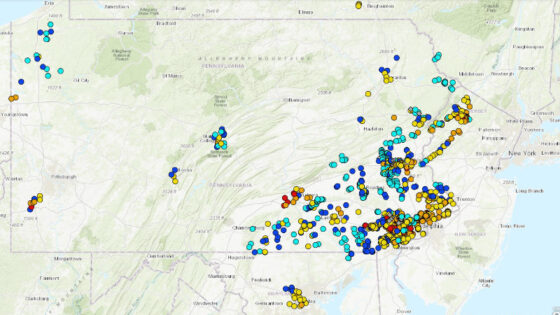

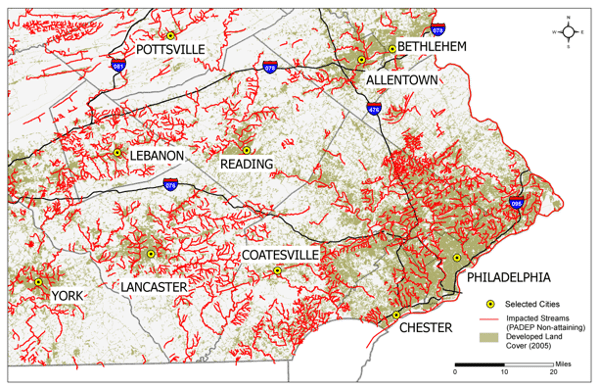

“We have examined many examples of healthy and unhealthy streams throughout Pennsylvania and found that the best streams drain highly forested watersheds and are relatively unpolluted, allowing them to support a wide variety of aquatic species. The best of the best are given Special Protection designations. However, by the time agencies designate streams as impaired, 50% to more than 90% of their sensitive species are missing. In those watersheds, most of the forests have been replaced by other land covers — such as farms, homes, and highways — and by more people. Together, these changes result in more intensive uses of land and water that negatively impact streams.”

Four Causes of Failed Stream Restoration

Jackson and Ehrhart describe four likely reasons why investment projects for restoring streams fail to achieve desired outcomes:

- Insufficient time for benefits to accrue.

- Inadequate project intensity.

- Misidentification of the root causes of impairment.

- Overlooking critical stressors, especially those that are new, increasingly common, or poorly known.

Among the scientifically studied restoration approaches that do not significantly improve stream health is one that’s particularly expensive, lucrative, and popular — stream channel and floodplain reconstruction. These reengineering projects target historical, manmade changes to a stream and its floodplain without considering the impact of increases in temperature, polluted runoff from urban and agricultural areas, and other environmental stressors.

How to Restore a Stream, According to Scientists

At the conclusion of their presentation, Jackson and Ehrhart describe the Stroud Center’s support of a whole-watershed approach to restoring streams and rivers. Instead of focusing on individual properties or stream segments in isolation, this science-based approach treats them holistically in relation to the land and other streams that connect them across an entire watershed.

Decades of research combining both experiments and field observations have led to the Stroud Center’s support of this approach. Because they are inherently dynamic systems that respond to changes in land use and climate, streams and rivers can be more successfully protected and restored by focusing on the entire landscape and engaging all landowners within a watershed. A key goal is to infiltrate rain where it falls and reduce pollution where it’s generated.

In the mid-Atlantic region, streamside forests are an important component of this strategy, buffering streams from pollution and human activity, providing wildlife habitat, stabilizing streambanks, normalizing channel dynamics, cooling stream water, and supporting diverse aquatic life.

Evidence of how reforesting the land around rivers and streams is key to restoring their health comes from a rich body of global research, including a decades-long study on the East Branch of White Clay Creek: Stroud Center scientists have been monitoring changes in a reforested section of the stream that runs through the Stroud Center’s headquarters in Avondale, Pennsylvania, and documenting notable signs of its improving health over time.

While their benefits are many and significant, streamside forests are not a silver bullet. Stroud Center scientists Bern Sweeney, Ph.D., and Denis Newbold, Ph.D., have found that even with 100 feet of forest planted on each side of a stream, 74% of nitrogen, 50% of sediments, and 40% of pesticides still reach the stream. Therefore, reducing pollution at its source — often on the landscape and farther away from streams — remains critical.

“People still need homes to live in, farms to grow food, and highways to travel on, so we have to know more about how to reduce these high-impact land uses on waterways. Ongoing research will further our understanding of how to protect and restore streams and rivers in urban and agricultural watersheds so that we have a more sustainable future,” says Jackson.

Support Science That Supports Fresh Water

The availability of clean fresh water depends on unbiased research to help people care for land and water. To support the trusted science needed for successful stream and river conservation, donate to the Stroud Center today.