How the Clean Water Act Changed the Trajectory of America’s Waterways and Became a Beacon for Freshwater Science

The Tipping Point

When U.S. legislators passed the Clean Water Act (CWA) in 1972, it was an overwhelming bipartisan response to a national outcry. Less than a year after the Cuyahoga River fire was featured in TIME in 1969, only months after the Santa Barbara oil spill, activists took to the streets for the first Earth Day. The consequences of degraded and desecrated natural spaces stood in contrast to the isolated beauty of a blue Earth rising amid the void in the now famous photograph taken on Apollo 8. Our nation had sent men to the moon for the first time, looking for meaning beyond our planet, only to stare in awe at the sanctity, rarity, and fragility of our home.

The movement that followed led to growing public awareness of environmental threats, multinational commitments to reduce them, and sweeping U.S. federal protections of land, water, and species.

Freshwater science, too, was advancing. A few years after Rachel Carson wrote Silent Spring, igniting public discourse around clean water and setting the stage for the CWA, Ruth Patrick, Ph.D., had an idea. A freshwater scientist at the then Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, Patrick, years earlier, had begun researching how all forms of life interact in a stream.

When, in the 1960s, Patrick met Dick and Joan Stroud, she had been looking for a healthy stream she could use to compare with the polluted ones she was researching and aiming to restore. The east branch of White Clay Creek, which snaked through the Strouds’ farm in Chester County, Pennsylvania, fit the bill. The Strouds agreed to let Patrick set up a laboratory on their farm, and they in turn challenged her to make freshwater science accessible, understandable, and useful to all people, not just scientists. Since then, Stroud Water Research Center has focused on one thing — fresh water.

The same year the CWA became law, a determined and inexhaustible team of scientists, led by then Director Robin Vannote, Ph.D., formulated the River Continuum Concept, which redefined a river as an interconnected physical, chemical, and biological system that is influenced by adjacent riparian, upstream, and upland conditions. The novel hypothesis positioned the Stroud Center to answer the call of the CWA to protect and restore the health of the nation’s waters. To this day, its 1980 publication in the Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences is the most highly cited article in scientific literature on streams and rivers.

By investigating what makes streams and rivers healthy, the Stroud Center — without allegiance to political parties, shareholders, or special interests — shares its unbiased knowledge of how to ultimately protect fresh water. This science has informed policymakers, such as through expert testimony on wetland protection provided to the U.S. Department of Justice, and has helped guide farm management, such as through the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s recommended reforestation methods.

Within a decade of Patrick establishing the Stroud Center, Robin Vannote teamed up with Bern Sweeney, Ph.D., to drop a second groundbreaking hypothesis, again shattering traditional thinking about freshwater ecosystems. The Thermal Equilibrium Concept explained how warmer temperatures threaten freshwater species gradually over time and generations rather than in a single catastrophic event, setting the stage for future research on how to best restore watersheds. (Hint: Reforestation, particularly within the riparian zone, is a key part of the equation.)

Time — The Great Healer and Revealer

The relevance of these two concepts today cannot be overstated as scientists seek to understand and remediate the effects of climate change and human activities on our freshwater resources. Stroud Center scientists have studied water quality in streams before and since the passage of the CWA, shedding a light on its force against the demands of a growing population. What they have found is that when conditions that support a healthy freshwater ecosystem are restored, time will heal many, though perhaps not all, wounds.

The White Clay Creek watershed, for example, has long been an agrarian landscape. When the Stroud Center was founded in 1967, cattle grazing and farming practices posed a threat to some portions of White Clay Creek. That changed in 1989 when the Stroud Center began a long-term restoration science project by planting trees along the streambanks. With funding from the National Science Foundation, and subsequent Experimental Ecological Reserve and Long-Term Research in Environmental Biology site designations, Stroud Center scientists began monitoring the stream’s forested, reforested, and meadow sections.

More than 30 years after reforesting, the long-term success of the project is coming into focus. The reforested sections are becoming wider, which could lower nitrate concentrations and provide better habitat for the bugs and other critters living in the stream. And although the biology of the reforested section still isn’t the same as that of the forested section, the improvement is unquestionably significant.

“Whether it’s in White Clay or the Chesapeake, whether it’s something we started more than 20 years ago or last year, all our research is tied in various ways to the idea that we need to know where and why streams are good and where and why streams are bad,” says John Jackson, Ph.D., who leads the Stroud Center’s Entomology Group.

The CWA, which Patrick helped draft, requires states to conduct water quality assessments and identify “bad” streams on a blacklist of impaired waterways, the 303(d) list. Fifty years later, more than half of U.S. rivers and streams still do not meet water quality standards for fishing, swimming, or drinking, according to the EPA. In Pennsylvania, where efforts to reduce water pollution have been aimed at the leading source — agriculture — the number of impaired waterways is lower: 30%.

However, Jackson points out that the freshwater landscape isn’t so black and white, that these numbers do not reflect the continuum of degradation: “A stream could be labeled as unimpaired and yet be very close to the line, meaning still significantly degraded. Every bad stream was at one time a fair stream, and every fair stream was at one time a good stream.

It’s like falling down a hill. The first step is to stop the fall. The next step is to start climbing back up. Anti-degradation is generally about stopping or preventing the fall. Restoration is about climbing back up.”

Restoration Science

On July 21, 2021, two Conestoga Valley High School teachers met up with the Stroud Center’s David Bressler and Rachel Johnson. Bressler, the community science program facilitator, and Johnson, a research engineer technician, helped the teachers install two EnviroDIY™ Monitoring Stations on Stauffer Run at the Lancaster County Country Club to capture water quality data in real-time. Jim Hovan and Kerrie Snavely, both science teachers, are incorporating the monitoring tool along with Monitor My Watershed®, an online data visualization tool, into their lesson plans on watershed science.

Stauffer Run is one of 18 streams that Lancaster Clean Water Partners is targeting to restore and ultimately remove from Pennsylvania’s list of impaired streams, a process called delisting. The Stroud Center is leading this effort for three of the 18 streams.

“Delisting a stream isn’t going to happen overnight. It could take us 10 years or longer, depending on stream conditions,” says Lamonte Garber, the watershed restoration coordinator. “Being delisted is symbolic but also practical. It means these waters would be safer for children to play in. It means wild trout would gain a foothold. And it would be a success story that encourages action on other streams.”

Restoration of these streams will be ushered through the Stroud Center’s Farm Stewardship Program, which connects farmers with financial incentives to implement farming practices that are better for stream health.

Three years ago, Stroud Center scientists began collecting baseline data on another of the targeted streams. Four landowners with farms along the stream have agreed to participate in the Farm Stewardship Program. A series of best practices, including streamside forests and fencing to keep cows out of the stream, are being staggered so that their immediate effects can be isolated. Over the span of years, decades even, scientists will monitor their cumulative impact on water quality.

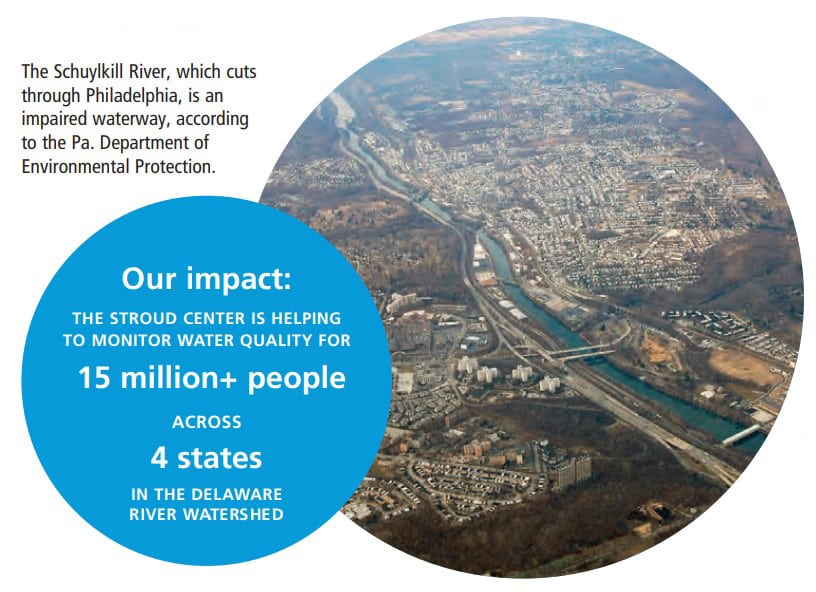

Diana Oviedo Vargas, Ph.D., who leads the Biogeochemistry Group, says, “Right now, the stream is in bad shape. It’s biologically impaired, but we’re hoping to change that.” The four farms in this headwater stream occupy over 80% of its watershed, providing a unique research opportunity. “Many times, it’s hard to evaluate the effectiveness of restoration activities because landowner participation accounts for a small fraction of the watershed, and any potential improvement becomes too diluted. In this case, we will have a better chance to quantify change and start to understand the impact when you target not just a stream, but a watershed,” says Oviedo Vargas. And that, says Jackson, would be the ultimate success story of the CWA. As one of dozens of organizations working to monitor, protect, and restore the Delaware River watershed, the Stroud Center is helping to understand the impact of watershed restoration on freshwater resources for more than 15 million people across four states.

“What we’re trying to do is balance the need for food with the need for clean water,” says Jackson. “In White Clay Creek, that balance has been achieved. The next goal is to replicate that at a much larger scale.”

Get Involved

Interested in monitoring water quality in your local area? Email us at communitysci@stroudcenter.org to become a community scientist today.