“Everybody’s connected to the land. Some less than others, but that’s what the general public gotta realize — hey, their food doesn’t come from a grocery store. There’s somebody out there raising it.”

Wise words from Randy Balthaser. He’s a fourth-generation farmer in Berks County, Pennsylvania.

Living in a concrete city, as most Americans do, it can be hard to make that connection. Balthaser and his wife, Traci, both grew up on farms. They enjoy raising their kids on the farm and working as a family. They have 400 acres of corn, barley, soybeans, rye, and alfalfa and keep 125 cows.

Balthaser’s connection to the land extends to managing the impacts his farming practices have on Northkill Creek. “We need to keep it clean. There’s stuff we did. That’s why I went to no-till,” he explains. No-till is a method of farming that does not disturb the soil through tilling, as is done with a plow. Studies have shown that it reduces erosion, increases microbial diversity in soil, and can even increase profits.

“The 40 acres here gets grazed just to keep everything green all the time. I know that helps [reduce] erosion.” Balthaser adds, “Everybody lives downstream.” What he understands is that any pollution from his farm, whether from fertilizer or erosion, that reaches the Northkill is a threat to water quality for everyone living downstream.

Stroud Water Research Center, the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and the Berks County Conservation District helped Balthaser secure funding for best management practices (BMPs) installed on his farm, including manure storage away from the stream and a forest buffer planted last year.

The Stroud Center has long advocated for forest buffers, with Stroud Center scientists publishing studies on them in the 1970s and initiating experimental tree plantings as early as 1982. Our scientists know from years of research that streamside forests can reduce the amount of polluted stormwater that reaches streams. Then, in 2004, they learned that forest buffers also help streams to process the pollutants that do get into their waters by supplying shade and food and enhancing the quality and diversity of stream life.

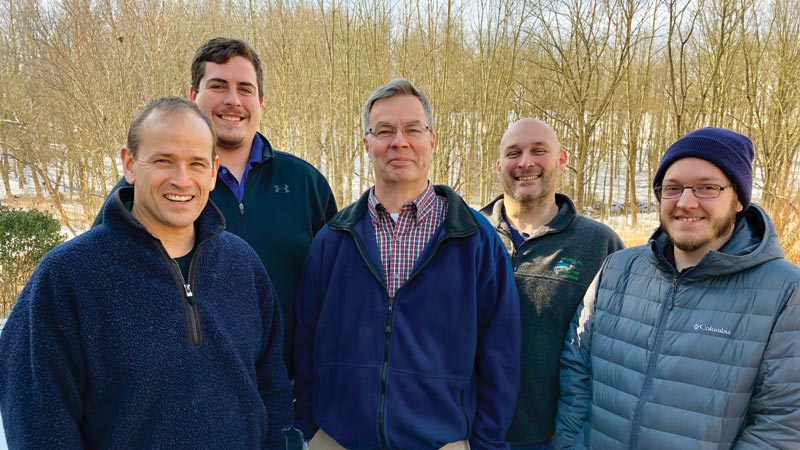

In the last six years, the Stroud Center has planted nearly 50,000 trees for clean water and healthy streams. It’s a pace that has steadily increased since the formation of the Watershed Restoration Group in January 2013 (now the Robin L. Vannote Watershed Restoration Program). Matt Ehrhart and David Wise helped launch the program as director and manager respectively. Lamonte Garber followed in 2014 to build relationships with landowners and restoration partners, followed by Calen Wylie in 2016, who is responsible for forest buffer care and evaluation.

Since its inception, the watershed restoration team has worked with 121 farmers to implement 1,337 BMPs. From left: Lamonte Garber, Calen Wylie, David Wise, Matt Ehrhart, and Matt Gisondi.

Without financial assistance, making improvements can be a challenge for many farmers, including Balthaser, who notes milk prices are a concern for him.

“On the whole, farmers want to do the right thing. They think about their legacy and stewardship,” says Ehrhart. “However, the cost of making barnyard improvements to keep cow manure out of streams, for example, can be prohibitive.”

Ehrhart and his team secure funding for best management practices (BMPs) through programs like the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection’s Growing Greener program. “In exchange, the farmers have to meet certain standards that will protect water quality and ultimately benefit the entire community. It’s a win-win.”

The team then connects farmers and landowners to conservation partners that help them implement BMPs. These can include a variety of improvements:

- The planting of forest buffers.

- Measures to manage barnyard runoff and capture and treat dirty water.

- Erosion control through cover crops, grass waterways, terraces, and no-till practices.

- Fencing and water systems to prevent overgrazing.

Beyond the farm, the Stroud Center has engaged well over 15,000 conservation professionals, landowners, and farmers through educational field days, presentations, and workshop trainings.

One of those conservation partners, the Chester County Conservation District, has provided technical assistance on several Stroud Center projects, including the Hurricane Sandy project. Christian E. Strohmaier, the conservation district’s director, explains that the Stroud Center’s watershed restoration team was the first watershed-focused group to understand the importance of compensating the conservation district. The technical assistance his team provides is specialized and has value. It includes surveying land and acquiring permits for the construction of BMPs like wetlands or level-lip spreaders, as well as their design and construction.

Strohmaier says, “The Stroud Center stepped up and basically said, ‘You know what, if you want technical assistance from the conservation district, you’re going to have to pay for it.’ What that has allowed us to do is have someone on staff who has at least part of their time available specifically for this kind of work.”

Since its inception, the watershed restoration team has worked with 121 farmers and more than a dozen partners to implement 1,337 BMPs. Some have gone on to win conservation awards. Deep Roots Valley Farm, a fifth-generation family farm run by Will and Kelly Smith were among four winners of the 2018 Clean Water Farm Award from the Pennsylvania Association of Conservation Districts. This came on the heels of a 2016 Farmer of the Year award from the Berks County Conservation District.

Empowering not just individual landowners, but the entire landscape of watershed professionals, is key, says Ehrhart: “The impact on our watersheds will be far greater when best practices become standard practices.”

This article was originally published in Stroud Water Research Center’s 2018 annual report.

By

By