By Marc Peipoch

There is an old Spanish saying that goes, “Patience is the mother of science.” Anyone who’s had a few hands-on experiences with science can surely relate to it. The truth is that fundamental questions about ecosystems can only be answered with an abundance of patience and long-term data. Stroud Water Research Center scientists are well aware of this fact and have been keeping a close eye on their backyard watershed for quite a long time.

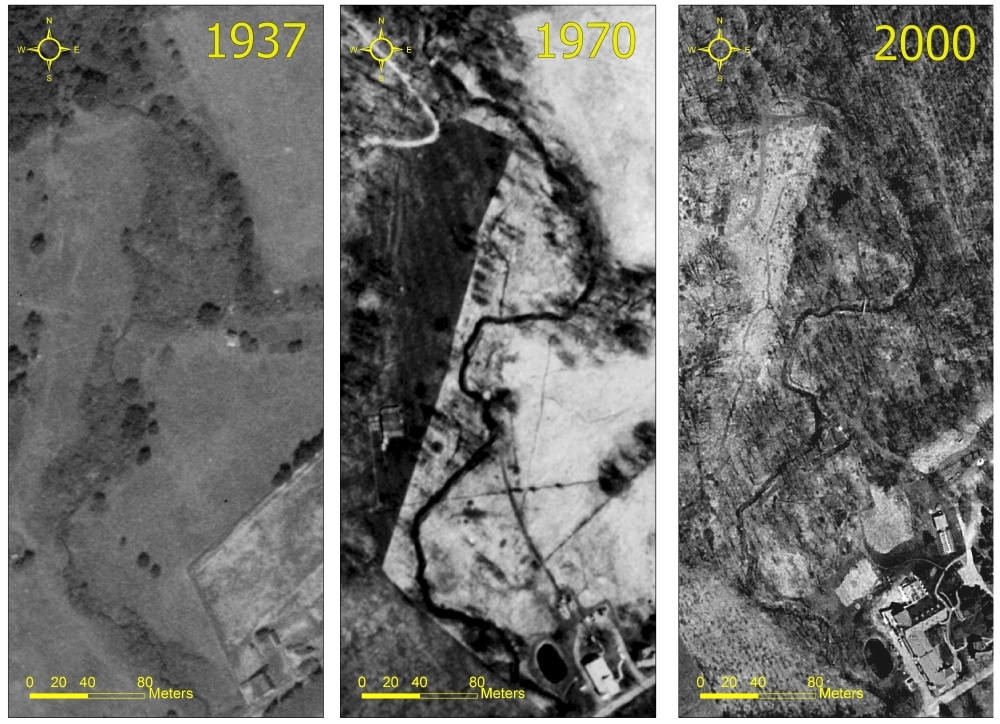

The White Clay Creek watershed, like most of the eastern North American landscape, experienced a dramatic deforestation and agricultural expansion over the last three centuries. These land use changes have stressed stream ecosystems, but it’s hard to say how they will recover from such impacts and to what extent restoration practices as reforestation can accelerate that recovery. Those are the hard questions involved in our decision-making process that are starving for long-term data to solve them.

In 1998, the Eastern Branch headwaters of White Clay Creek, north from the Stroud Center, were designated as a site for long-term research in environmental biology by the National Science Foundation (NSF). This designation recognizes a unique opportunity for long-term research on the effects of riparian reforestation on watershed ecosystems.

NSF funds help the Stroud Center maintain reference (forested), reforested, and meadow sections along the creek in which research staff collect physical, chemical, and biological data (including microorganisms, fish, and invertebrate communities) to provide a comprehensive picture of the watershed’s response to riparian reforestation.

The long-term effects of reforestation to stream ecosystems are beginning to reveal themselves through more than 20 years of data.

Stroud Center Associate Research Scientist Melinda Daniels, Ph.D., and her team have been meticulously documenting how the reforested section is getting wider at a rate of three inches per year. This is fast for a stream like White Clay Creek, and it shows the power of forest regrowth to help stream channels heal themselves. Daniels expects that the stream banks of the reforested section will eventually widen and stabilize to the same extent as those in the reference section with forests established more than 100 years ago.

Wider stream channels could lower nitrate concentrations in the forested section of the creek observed by Stroud Center Assistant Research Scientist Diana Oviedo-Vargas, Ph.D., and her team. Wider channels increase surface contact between water and the streambed providing a better chance for stream organisms to take up some of these nutrients.

Developing a full riparian canopy must precede the recovery of healthy macroinvertebrates communities because leaf litter falling into the stream is a primary food resource for many macroinvertebrate species that are most affected by decades of deforestation.

Entomologists at the Stroud Center led by Senior Research Scientist John Jackson, Ph.D., have found that the macroinvertebrate community structure in the reforested section is still different from the reference (forested) section. The bright side is that the difference between these two macroinvertebrate communities has decreased dramatically over the years.

Learn More

- Read about the Stroud Center’s stream and watershed restoration science and practice.

- Check out a video about the role riparian forests play in promoting stream health.

- View links to dozens of peer-reviewed research publications from our long-term research in Pennsylvania and Costa Rica.