Stroud Scientists at Work

Fish Ecologist and Geneticist, Dr. William H. Eldridge, Joins Stroud Water Research Center to Launch its Fish Molecular Ecology Department

Willy Eldridge recently joined Stroud Water Research Center to launch its Fish Molecular Ecology Department. He received his doctorate from the School of Aquatic and Fisheries Sciences at the University of Washington and was formerly a lecturer at the University of Washington at Tacoma and a fishery geneticist at the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission.

We sat down with Willy to discuss his new role and to put into context what fish ecology really means to him and the Stroud Center. Following are excerpts from that interview.

What Exactly is a Fish Molecular Ecologist?

The answer to this has three parts. First of all, of course, we study fish. Fish are incredibly interesting. For one thing, there are lots of them; more than 25,000 species exist all over the world, which is far more than all the other vertebrate species combined. And fish are valuable in a variety of ways — from economics to research.

Secondly, we study fish genetics. We are concerned with preserving fish diversity and want to understand their ability to adapt to changing environments. As geneticists, we take the long-term view, ensuring that diverse fish populations will still exist 100 or even 1000 years from now.

Finally, as ecologists, we study fish in their particular environments — both the physical environment of the waters and watersheds in which they live and the social environment composed of the other organisms with which they interact.

What Prompted You to Focus Your Research on Fish?

Fish have always fascinated me. There is enormous diversity, not only among different fish species but even within the same species. Fish can have very different characteristics, depending on where and how they live.

They’re widespread; you find them all over the world.

For a variety of reasons, fish are model organisms for research in environmental biology and other areas. Model organisms are those that can be used to learn about biological processes shared with other organisms. For example, Zebrafish are used as a model of early growth and development because they are mostly transparent when young, so organs and other internal tissues can be observed directly without the need for dissection. Many scientists use fish as models to study genetic processes in their efforts to learn things about DNA and evolution.

Fish have enormous economic importance. They are a major source of food for much of the world’s human population. Originally, all fish came from the wild, but increasingly they are being produced on “fish farms.” In 2007, for example, aquaculture accounted for almost half the fish consumed by humans, and that number continues to rise – both because of the ever-growing global demand for protein and the continued depletion of wild stock. Right now, most of the salmon, shrimp, catfish, and tilapia consumed are raised on farms. In addition, recreational fishing is a significant source of revenue for many countries. I believe that my research on fish can yield important information that will help guide best management practices both in aquaculture operations and in natural populations.

Finally, because fish are often at the top of the food chain in streams and rivers, they are a good “indicator” species for understanding the overall health of the freshwater ecosystem in which they live. So it’s important to pay attention to them.

What’s the Focus of Your Current Research?

One of the projects I’m working on right now is a study of how fish respond to changes in their environment.

We humans put a lot of pressure on our natural ecosystems, and consequently, we put a good deal of stress on fish populations. My study is focused on sub-lethal responses to such stress. Even though fish may not always die in response to environmental changes, their bodies respond in ways that may not be immediately visible but are extremely important to their survival. And their survival is important to our survival.

In this study, we are looking at environmental changes that may affect their overall health, susceptibility to disease or predation—even their reproductive rates.

Exactly What Kind of Environmental Changes Might Affect Freshwater Fish Populations?

Changes can range from man-made to natural stressors, which means that all sorts of things could be factors that adversely impact freshwater fish populations.

While certainly not a comprehensive list, potential stressors might include: the building or removal of a dams, certain methods of fishing, contaminants in our streams and rivers, the introduction of non-native or farm-raised fish species. Changes to the land use and vegetation surrounding a stream or river, such as deforestation, can also have a negative effect on fish.

We are trying to understand how each of these things impacts specific fish populations so that we can make the kind of informed decisions that will preserve fish diversity and protect the ecosystem.

Why Did You Leave the University of Washington in Seattle to Work for the Stroud Center?

The reputation of the Stroud Center among its scientific peers was a huge draw. It’s exciting to be part of such a great team.

Being able to work under the same roof with an interdisciplinary group of scientists is a unique opportunity that will both make my research better and allow me to add a dimension that will enhance the work of my colleagues.

And because the Stroud Center does work all over the world, I can expand my research beyond fish native to temperate rivers and streams to tropical freshwater species as well.

The Stroud Summer Internship Program: Grooming Future Scientists

Each summer, the Stroud Center welcomes a new group of college interns who are eager to participate in research projects at the Stroud Center and to begin what will likely become their life’s work, a career in the sciences.

The program, now in its 36th year, has ushered through more than 260 interns who have come in search of meaningful work and whose passion for science and the environment has prompted them to spend their summers with us. The interns work under the direction of our interdisciplinary team of seasoned scientists — all able mentors — who ensure that their jobs don’t just contribute to the research of the Stroud Center but also build human capital. The critical skills and knowledge these interns gain over the course of the summer are essential for the careers they may ultimately pursue full-time.

“The internship program acts as a proving ground of sorts,” says Lou Kaplan, senior research scientist and principal investigator of the Biogeochemistry department. “Experiences like this help to develop the critical thinking and problem-solving skills these students will need to go to the next level as independent researchers. It’s invaluable because it also allows them to see for themselves if they have the passion and fortitude to sustain themselves during the challenges inherent in research. By the end of the summer, they can evaluate whether they like the lab and field work, as well as the collaborative interactions required to be successful in a career in the environmental sciences.”

Interns hail from colleges in Georgia, Indiana, and Ohio, as well as the Universities of Delaware and Pennsylvania. Their courses of study span the sciences from environmental studies to molecular biology. This lucky group of individuals is culled from a much larger group of applicants, each of whom endured a vetting process, complete with resumes and interviews — and the similarity to the work world doesn’t stop there.

As they immerse themselves in their research projects, the interns also benefit from weekly lectures presented by senior scientists, and they participate in a journal club, where along with Ph.D. candidates and Stroud Center scientists, they read and discuss original research articles published in scientific journals. By summer’s end, these interns will have gained enough knowledge and confidence to present their own scientific papers, both to their peers and the general public, about a specific scientific topic or on their own research — an exercise designed to test their understanding of the subject, to educate others, and to give them a taste of what will be expected in their future studies and as independent researchers.

“This program is clearly a win-win for everyone involved. We’re able to expand the depth and breadth of our research programs and cultivate great talent at the same time,” said Bern Sweeney, Director of the Stroud Center. “Each year, several of our interns return — and we’ve had the good fortune to recruit some of our best employees directly from the internship program.”

An Intern Tests Her Own Hypothesis

Neva Cockrell, an Oberlin College undergrad, is spending the summer as one of a select group of interns participating in the Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU) program, funded by the National Science Foundation. REU interns are required to conduct research of their own design — from the proposal stage through execution, analysis, and written and oral presentations of the results — with guidance from a Stroud Center scientist at each step along the way.

Under the umbrella of the Long-Term Research in Environmental Biology (LTREB) project, a collaborative study that involves multiple departments at the Stroud Center, Cockrell designed a research project to answer a fundamental question about how streamside (or riparian) vegetation affects the mixing of groundwater and stream water and the biological processes that occur below the streambed surface (or hyporheic zone.) She will test whether more nitrogen is removed through the hyporheic zones within the streambeds of forested stream reaches than in reaches adjacent to meadows, where the riparian zone is comprised of grasses alone.

“A lot of nitrogen, often from agriculture, enters the groundwater and ultimately the stream, bypassing the root system of any plants in the riparian buffer — streamside forest or meadow,” said Neva. “It does that when groundwater flows up through the streambed. So, measuring the biological processes and the water movement in that streambed tells us how nitrogen is being removed or processed between the land and the stream.

“Because the streams are wider in forested reaches, the streambed is larger,” she added, “and I wanted to know if biological activities are also magnified as a result of this phenomenon—and, if so, what effect that has on the stream ecosystem.

“If we don’t understand how agricultural chemicals enter the stream, then we can’t implement effective buffer zones to keep the stream healthy.” The data she collected will contribute to a broader understanding of the impacts of different land use practices (forested, meadow, agricultural) on stream health and water quality.

How She Did It

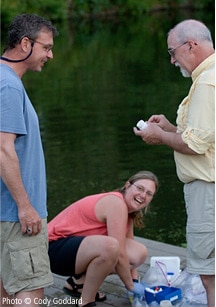

Cockrell sampled water from 18 shallow plastic wells inserted into the streambed and distributed equally in forested and meadow reaches of White Clay Creek. She assembled the wells herself and placed them at 3 different depths below the streambed surface. She then collected water samples from three depths and analyzed them for nitrate concentrations.

Special Events Update

Face-to-Face with 80 Tons at The Water’s Edge

At 80 feet long and 80 tons — so big that an African Elephant The Whale Trust’s guiding philosophy is that science — the quest for answers to the most intriguing questions about our natural world — lies at the heart of environmental education and conservation. could stand on its tongue — the Blue Whale is almost mythical in size. And that’s just part of the attraction for Flip Nicklin, contributing photographer for National Geographic magazine, the foremost whale photographer in the world — and our featured speaker at The Water’s Edge fundraising gala on October 2nd, 2008.

“The more you know of whales, the more it sounds like fiction,” said Nicklin, chuckling over the notion that we think we know so much — until we learn some more. Nicklin has spent much of his 30-year career, along with research colleague Jim Darling, absorbing the myth and magic of whales and adding to it biological studies. With the proceeds from the sale of his photo collection to Minden Pictures in 1996, Nicklin started the Whale Trust, a not-for-profit research and education organization based in Hawaii. The Trust’s guiding philosophy is that science — the quest for answers to the most intriguing questions about our natural world — lies at the heart of environmental education and conservation.

“I was destined to be a diver,” says Nicklin, reflecting on the family lore that was the catalyst for his illustrious photographic career and his life’s passion — the Whale Trust. Nicklin’s maternal grandfather was a hard-hat diver and pile driver who built things for a living; preparing for an underwater construction project, he died in full dress, the victim of a whirlpool accident; his body was never found. Nicklin’s father ran a diving equipment operation. In 1963 his father and a buddy were thrust into the public eye when they encountered a whale entangled in fishing nets and set out to untangle it. This first-ever “whale ride” prompted National Geographic underwater photographer Bates Littlehales to pay him a visit — and thus, the young man, Flip, met one of his first mentors.

Since then, Nicklin has spent his life largely underwater. Credited with 20 National Geographic feature stories and several books, he is an expert on whales — and can free-dive to depths of 80 feet among these magnificent creatures. Asked why he would put himself in potential danger, he recalled his first encounter underneath a 40-foot Humpback whale. “This is bad,” he thought but subsequently came to see that “whales are like dogs; they’ve each got a different personality. They’ll give you a warning — and you know when to stay away.”

Please don’t miss this year’s Water’s Edge. Join us at Longwood Gardens on Thursday, October 2, at 6:15 p.m. for Flip Nicklin’s presentation, Whales, A Changing View.

Introducing the Mayfly Club: Our Next Generation of Watershed Stewards

The Mayfly Club, a membership and volunteer group of young adults, is dedicated to raising awareness and support for the Stroud Water Research Center and the issues facing the world’s supply of fresh water. The club was named for one of the most pollution-sensitive macroinvertebrates, the mayfly — of which there are approximately 2,000 species worldwide — because of its key role in alerting us to changes in water quality. Through a combination of social events and educational workshops, the club seeks to raise awareness about freshwater issues, help fund the Stroud Center’s programs — and have fun doing both.

More and more, our news headlines are about water — and the issues that these stories raise are increasingly hard to ignore. Whether we’re talking about contamination, flooding, or drought, many of us are asking what we, as individuals, can do to help address these problems.

“The good news,” said Billy Peelle, co-founder of the Mayfly Club, “is that by being informed, we can make small changes in our habits that will make a significant difference. And, that’s really what the Mayfly Club is all about.”

“Fresh water is a finite resource,” said Gayley Blaine, co-founder of the Mayfly Club. “I’m hoping that our efforts can encourage others to conserve water and protect our watersheds.”

There are simple and cost-effective ways to protect and improve the quality of our streams, which are the source of much of our drinking water. One of the most important is to restore trees along the banks. That’s why the club will be getting together this fall to plant a streamside forest along the banks of a tributary of the Brandywine River in West Chester, Pennsylvania.

Mayfly Club members share a passion for the environment and a commitment to watershed stewardship.

Water Facts

Did you know?

FRESH WATER = LIFE

- 18% of the world’s population lacks access to safe drinking water (WHO, UNICEF 2005)

- 12 million people die each year from lack of safe drinking water (WHO)

- More than 80% of the disease in developing countries is related to poor drinking water and sanitation (WHO)

- Approximately 50% of the world’s wetlands have been lost (UN-DESA)

- More than 20% of the world’s known freshwater species have become extinct, threatened or endangered (UN-DESA)

SIX STEPS TO CLEANER STREAMS

- Reduce your home water use.

- Inspect and maintain your septic system.

- Avoid using pesticides and fertilizers on your lawn.

- Switch to non-toxic household cleaners.

- Plant trees.

- Remember — we all live downstream.

Your Choices Make a Difference.

Virtually everything we produce, and most of what we do, requires water — and lots of it. Just how much?

IT’S A FINITE RESOURCE

Learn To Conserve

- Only 1% of the world’s water supply is available for drinking.

- The water we use is the same water the dinosaurs used.

- The average American uses 100 gallons of water per day — 40 times more than the rest of the world’s population.

- In parts of the U.S., China and India, people are consuming groundwater faster than it is being replenished.

- Many rivers — from the Colorado River in the U.S. to the Yellow River in China — no longer flow regularly to the sea.

SIX STEPS TO WATER CONSERVATION

- Cut 1 minute from your shower — and save >700 Gallons/Month

- Fix that leaky faucet — and save >1,225 Gallons/Year

- Turn off running water when you brush your teeth — and save >3 Gallons every time

- Install a low-flow toilet — and save >4 Gallons per flush

- Reduce your meat consumption; eating low on the food chain saves water

- Replace your lawn; native plants and grasses require less water

Stroud Educators at Work

Spanish-Language Leaf Pack Experiment Kit: Fall Workshop Will Kick Off Pilot Program

The 2008 Schuylkill Sojourn: An Opportunity To Teach Stewardship

Hundreds of people, including Stroud Center educator Christina Medved, embarked on a seven-day, 112-mile canoe trip down the Schuylkill River — from Schuylkill Haven to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania — in June. The 10th annual Schuylkill Sojourn, organized by the Schuylkill River Greenway Association, was intended to deepen the appreciation for the Schuylkill River, a river steeped in history, by those who rely on it for everything from recreation to their drinking water.

Few river basins have had a longer or stronger connection to socioeconomic, cultural, and industrial development in the United States than the Schuylkill, whose land and water have provided many of the resources needed over the 350-year history of colonial, industrial, and even modern Philadelphia.

Today, the Basin bears little resemblance to the pristine woods the first Europeans found. However, it is still an invaluable natural resource for the 3 million people who live in the watershed as well as the additional 3 million people from neighboring watersheds who together make up the Philadelphia metropolitan area.

Medved not only paddled the length of the river — but with fellow Stroud educators Kristen Travers and Vivian Williams, she also educated the Sojourn participants about the Schuylkill’s water quality and the Center’s 12-year+ research on the river and its tributaries.

The trio of educators showed sojourners how to conduct chemical tests of water quality on the river at every lunch and overnight stop along the route. Parameters tested included air and water temperature, transparency, pH, conductivity, and dissolved oxygen and nitrate levels in the water. The data was documented and posted throughout the trip.

“It was especially gratifying to see the paddlers express genuine interest in the results of our water quality testing,” said Medved. “They clearly wanted to become more educated about the quality of the water on which they were paddling. They constantly checked our posted results and asked fantastic questions. We’re already planning to conduct more extensive tests on next year’s Sojourn.”

Learn more about the Stroud Center’s studies on the Schuylkill and its tributaries.

What’s under the Schuylkill? Check out our photo gallery of some of its smallest but most important inhabitants—the macroinvertebrates that call the Schuylkill home.

In the News

Bernard Sweeney: Conversations with WHYY TV 12 and WHYY Radio

The role of streamside forests in reducing pollution in Pennsylvania’s streamside forests is a subject Bernard W. Sweeney and the scientists at the Stroud Center have studied extensively, which is why WHYY came to us to learn more in July.

The Stroud Center’s efforts to restore the streamside forest (or riparian buffer) beside the White Clay Creek, an Exceptional Value stream in West Chester County, Pennsylvania, has a profound impact on Delaware residents. WHYY TV12, the public broadcasting station serving 2.6 million households in southeastern Pennsylvania, Delaware, and South Jersey, wanted to know why, so they sent Science and Health Reporter Kerry Grens to cover the story for WHYY DELAWARE TONIGHT’s August 5 evening broadcast.

Stroud Scientists and Educators Present

Disseminating Our Findings to Our Peers and the Public at Large

Our ability to disseminate our findings to a broad audience allows us to increase awareness and create a public dialogue centered on the protection, preservation, and restoration of watersheds everywhere. It’s for that reason that our scientists and educators engage in both scientific and public forums to share their findings. The following highlights recent presentations.

AMERICAN WATER RESOURCES ASSOCIATION (AWRA)

Stroud Center Senior Research Scientist and Director Bernard W. Sweeney gave the July 1 keynote address at the 3rd quadrennial AWRA Riparian Ecosystems and Buffers Conference: Working at the Water’s Edge. The conference, which draws its speakers from among the most prominent scientists in the fields of riparian ecosystems research around the world, attracts a diverse audience of scientists in addition to water resources specialists, land management planners, watershed and environmental groups, students, teachers, and government and corporate policymakers. This AWRA Summer Specialty Conference was focused on best practices for the management of critical riparian landscapes. Sweeney’s presentation, Trees, Streams, and Water Quality, was met with enthusiasm by the group of 250 academics and resource management professionals from around the country.

Stroud Center staff scientist Susan Herbert also presented findings from a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) National Monitoring Program on the importance of streamside reforestation for reducing nonpoint-source pollution in small streams. Results from this study, led by principal investigator and research scientist J. Denis Newbold, indicate that 10 years after planting a streamside forest, the nitrate and sediment export from the watershed are reduced by approximately 30% and 55%, respectively.

HISTORIC YELLOW SPRINGS

The mission of Historic Yellow Springs (HYS) in Chester Springs, Pennsylvania, is to share, preserve, and celebrate the unique living village of Yellow Springs. They do so by focusing on history, arts, education — and the environment, which was the subject of guest lecturer and Stroud Center senior scientist John Jackson, who presented The Health of the Waters of the Schuylkill River Valley on June 25th.

AMERICAN HORTICULTURAL SOCIETY’S 16TH ANNUAL NATIONAL CHILDREN & YOUTH GARDEN SYMPOSIUM

Stroud Center educator Vivian Williams presented Dream Scene — Gardening for Stormwater to attendees of the American Horticultural Society’s annual National Children & Youth Garden symposium hosted by the University of Delaware on July 24-26, 2008. Williams discussed ways in which to involve youths in using and presenting best management practices for conserving water in the garden. She spoke about how trees, rain gardens, impervious surface materials, green roofs, and rain barrels are all part of the arsenal of tools for intercepting and redistributing water. Finally, Williams introduced the Media Rain Barrel Project, a program conceived by Stroud Center educators for school-aged students. This program aims to use rain barrels as a canvas for educating the public about best management practices for dealing with stormwater and recharging groundwater.