Stroud Scientists at Work

Unearthing Buried Treasure in Papua New Guinea

Exploring the Long Route Back to Healthy Streams

By Diane Huskinson

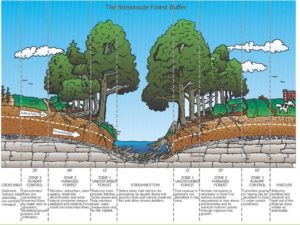

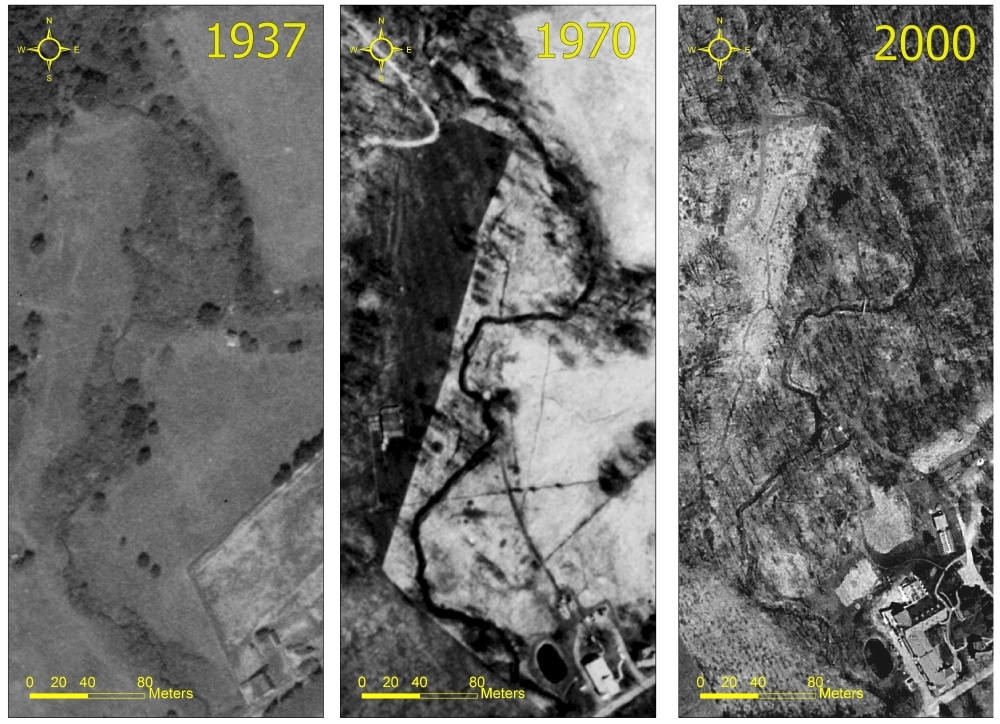

Along the banks of East Branch White Clay Creek (WCC), which runs through southern Chester County, was once a cow pasture. The cattle grazed an area overgrown with invasive plant species but little else to combat stormwater runoff. Although upstream reaches comprised one of the best piedmont streams in southeastern Pennsylvania at the time, its condition within the pasture was not ideal. With too many cows and too few native trees, life inhabiting this local stretch of stream survived amid regular disturbance and with less oxygen, higher sediments, warmer temperatures, and an altered food base. The result was reduced stream health, evident in the presence of an insect community composed of too many pollution-tolerant species like black flies and chironomid midges and too few pollution-sensitive species like mayflies and stoneflies.

THEN CAME THE RETURN

Then, in 1967 the establishment of Stroud Water Research Center catalyzed a return to health and vitality. The cattle were removed, and the cow pasture became the site for the Stroud Center’s headquarters. A complete restoration and reforestation of the riparian zone followed beginning in the mid-1980s.

Today, WCC is breaking a new course. Out of 18 sites throughout the WCC watershed, the area upstream of Spencer Road — the area of restoration and where the Stroud Center is located — is the only site found to be in good condition based on stream samples collected from 1991 to 2008. This fact is promising yet curious. Promising because we know that once a stream is in a state of decline, it is not traveling to a point of no return. Yet it also raises more questions, for the route back to stream health is a long and unfamiliar one.

CHARTING THE COURSE

In an unprecedented, long-term study of the effects of landscape restoration on stream ecosystems in WCC, Stroud Water Research Center scientists have set out to chart that unexplored course.

“We have known for years that the reforestation of stream banks is perhaps the single most import step that can be taken to improve water quality and stream health,” said Dr. Louis A. Kaplan, senior research scientist at the Stroud Center. “What we do not know is the sequence of events or time frames needed to reach certain milestones along a stream restoration trajectory.”

That’s because a study of the long-term impacts on streams after landscape restoration has never been done before. To do so requires a rare blend of resources: a research site with long-term availability, the right technology, funding, and the collaborative efforts of scientists from a variety of fields. Stroud Water Research Center is unique in its ability to bring all such resources together.

This February, the National Science Foundation (NSF) awarded the Stroud Center a Long-Term Research in Environmental Biology (LTREB) grant. The grant will allow Stroud Center scientists to use cutting-edge technologies to collect new data on everything from the shape of the stream channel to the food resources of the insects and fish living in the stream.

Stroud Water Research Center first received an LTREB grant in 1998 to characterize the sequence of changes in the physical, chemical, and biological attributes of the stream; this new grant will extend those studies as the forest continues to mature.

The Stroud Center’s team of scientists, including microbiologists, entomologists, biogeochemists, fish ecologists, and geochemists, has been collecting data from WCC for over 40 years. And now, over the next five years, they will be able to build on that data to investigate how the ecology of a stream changes as trees planted along the stream banks mature.

“We now have the ability to gather near-real-time data wirelessly from dozens of sites throughout White Clay Creek,” said Dr. Anthony Aufdenkampe, assistant research scientist and one of the grant’s co-principal investigators. “Using this technology, we can measure the continuous flux of nitrogen and carbon in the stream.”

By measuring the removal of these nutrients throughout aquatic ecosystems, the scientists can gain a clear understanding of how a stream changes over time once the surrounding landscape has been restored.

Research Scientist Dr. Denis Newbold, another among the team of investigators, said, “A stream’s ability to reduce polluting levels of nitrogen depends upon many factors within the stream. Part of our job will be to look at those factors. Our hypothesis is that the landscape restoration along White Clay Creek will increase the stream’s ability to moderate nutrient levels.”

Insects, too, will play an important role in the study.

“Insects can tell us a lot about the health of streams,” added John Jackson, senior research scientist and also one of the grant’s co-principal investigators. “For example, mayflies are ancient freshwater insects that have been around for over 350 million years. They are native to streams throughout the world, including southeastern Pennsylvania, but because they are intolerant of many pollutants such as excess sediments, low-dissolved oxygen, and many herbicides and insecticides, they are found less frequently in polluted streams. However, polluted streams are not dead; they can be teeming with pollution-tolerant species such as chironomid midges, worms, and black flies. It is this difference that allows us to classify streams as healthy or unhealthy.”

THE BIG PICTURE

What Aufdenkampe, Jackson, Newbold, and Kaplan, the project’s director, find will be analyzed together like the pieces of the puzzle.

“This grant represents the combined efforts of all research fields at the Stroud Center and builds on the collaborative science that is a hallmark of our organization,” said Kaplan.

Those efforts will allow the scientists to answer three basic questions:

- How and in what order do factors such as light and temperature change over time?

- As stream restoration progresses, is carbon — the backbone of all life on Earth — processed throughout the food web more efficiently?

- How does the processing of energy resources such as carbon and nitrogen, scale with the degree of restoration?

The answers to those questions will be invaluable to communities and governments by offering insight into what to expect from restoration projects.

“Understanding how the health of a stream changes over time following restoration will provide much-needed information and guidance for the billion-dollar-a-year stream restoration industry, government agencies that regulate the projects, and taxpayers who often fund the projects,” said Kaplan.

The project will also benefit students, educators, and the greater scientific community. The Stroud Center will publish project data on the Web, and the Education Department will use that data to help middle- and high-school science teachers incorporate the use of long-term, environmental data into the classroom to enhance students’ science skills and environmental knowledge. There will even be an opportunity for online graduate work for teachers through Millersville University.

Of course, any research project is fundamentally a quest for knowledge. With sound science and thorough investigative skills, Stroud Center scientists working on this project will bring to light yet unknown facts about restored streams and in so doing foster public understanding and appreciation of the deceivingly complex workings of freshwater ecosystems.

Stroud Educators at Work

Beyond Borders: Costa Rica Leaf Pack

By Dr. Jamie Blaine

The Leaf Pack Network® continues to move beyond any borders of nation, language, or culture. A recent workshop in Costa Rica brought together individuals from a variety of fields and locations with a mutual desire to communicate and learn.

Less than a week after massive November flooding that ravaged Costa Rica, Christina Medved and Dr. Jamie Blaine arrived to lead a two-day Leaf Pack workshop in the country, where huge washouts provided a harsh reminder of the power of water. Stroud Water Research Center board member Steve Stroud, who is president of Asociación Centro de Investigación Stroud (ACIS), the Center’s sister organization in Costa Rica, drove them to the workshop’s site in Barú, where they were joined by Rafa Morales, who manages the Stroud Center’s research station near the Nicaraguan border.

Sponsored by the Asociación de Amigos de la Naturaleza del Pacífico Central y Sur (ASANA), the workshop is yet another legacy of the Leaf Pack Ambassadors program, which grew out of a weeklong workshop the Stroud Center hosted in the fall of 2008. Teachers, conservation workers, and government officials — from Mexico to Peru — attended that event, and each of the 18 participants was required to offer a workshop after returning home. The goal was to have the Leaf Pack Experiment spread across Latin America the way ripples from a tossed pebble spread across a pond.

Several of the participants in the Ambassadors program have ties to ASANA, which saw an opportunity to use Leaf Pack to launch a grassroots effort to protect the watersheds in Costa Rica’s Path of the Tapir Biological Corridor — and the 20 or so rivers that flow wholly within its boundaries. ASANA wanted to train local teachers, and ultimately students, and citizen action groups to use Leaf Pack in this effort; and Pitzer College in California offered to host the two-day workshop at its Firestone Center for Restoration Ecology, a biological reserve and a field research and education site, where both Isabel Arguello Chaves, the onsite director, and Dr. Cheryl Baduini, her U.S.-based supervisor, are graduates of the Ambassadors program.

LEARNING MEANS EMBRACING THE SCIENCE OF DISCOVERY THROUGH THE ART OF PLAY

The workshop participants divided their time between indoor lectures, discussions, and labs and trips to nearby streams to analyze leaf packs and learn other methods for water assessments and long-term monitoring. Their enthusiasm was infectious. At the outset, these grown men and women were challenged to release their inner child and create their own “watersheds”: they crumpled paper, colored lines along the ridges with magic markers, and then poured water over the paper to see how this “watershed” would react. Everyone jumped in, talking in halting English and pidgin Spanish — translating for each other, asking questions, offering personal anecdotes, telling stories, and taking ownership of the program. This was truly a cross-cultural conversation in which the barriers of language and culture gave way to a mutual desire to communicate and to learn.

Christina Medved, education programs manager and Leaf Pack Network® administrator at Stroud Water Research Center, commented, “It was a learning experience for all of us. The participants showed me the beauty of their watershed while teaching me about the issues they face and are seeking to address. And it was exciting to give a workshop so far from home, to hear the participants translate my words into Spanish and see their eagerness to learn about their streams.”

And learn they did. Participants were tested at the outset of the program, and then tested again two days later. Their scores had improved by over 60 percent.

PLANTING THE SEEDS OF UNDERSTANDING AROUND THE WORLD

The participants consisted of employees and board members of ASANA, ecotourist guides, educators, and representatives of foundations and government agencies. They included Roberto Quiros of the Omar Dengo Foundation, which holds annual teacher workshops all over Costa Rica, and Mileidy Castro Gonzalez, the regional director of the Ministry of the Environment. The workshop graduates will now train teachers, students, and community volunteers on how to assess and monitor stream health. Collectively, they represent another step to ensure that the Leaf Pack program continues its expansion throughout Costa Rica and across Central and South America.

ASANA has selected 10 communities to be part of its new Leaf Pack project. Each has a well-organized water association and an elementary or high school that is part of a regional long-term environmental education program. After presenting a series of workshops, ASANA will designate community teams, composed of both adults and students, to evaluate their watersheds twice a year — once in the dry season and once in the rainy season. The goal is to have the program financially self-sustaining after two years.

In addition to hosting all the ASANA workshops at its Firestone Center, Pitzer College will continue the program it launched after the Ambassadors workshop, in which Baduini comes twice a year to teach the Leaf Pack Experiment to college students, who in turn work with college staff and local teachers to provide programs for the region’s elementary schools. The goal of the program, said Arguello, is “to confirm the condition of the water and to have fun doing it.”

Finally, both Roberto Quiros of the Omar Dengo Foundation and Mileidy Castro of the Ministry of the Environment expressed their intention to integrate Leaf Pack into their programs.

These efforts reinforce the goal of the Stroud Center to plant seeds that will grow into a deeper understanding of water issues and a broader effort to protect water sources around the world. By collaborating with local peoples, the Center can help those who best know their own communities to defend the lifeblood of their watersheds.

What Did the Participants Think About the Workshop?

“Great work—useful and easy to understand.”

“Excellent program and very applicable, thank you!”

“I found it all super interesting and useful. Thanks for everything.”

Leaf Pack Network® Helps Urban Kids Explore Salty Waters in Death Valley

By Angela Horvath

DANCING IN THE DESERT

If you visit Salt Creek, Death Valley on any given afternoon in the spring, you’d be walking along the boardwalk in shorts and a t-shirt, the weather a balmy 72 degrees Fahrenheit. You would also have to navigate through 60 school kids, all staring into the frothing waters.

The kids have come to make leaf packs, designed by Stroud Water Research Center as a tool to assess stream health, but have stopped to watch the pupfish breed in the shallow rivulets of Salt Creek. The males put on a fabulous dance in blue and yellow; their mating colors attract females and show just how virile they are. Thousands of visitors watch them spar for mates each year, and what a rare tournament it is! Pupfish swim only in early spring, through streamlets that are warm, salty, and — most of the year — dry as a bone.

On the main valley floor, two springs saturate the Death Valley soil: Salt Creek and Badwater. As both names imply, the water isn’t suitable for most life. The waters are sometimes 1.5 times as salty as the ocean. Over 100 years ago, settlers passing to the gold fields of California gave Death Valley her ill-fated name. Their oxen succumbed to the bitter waters that gurgle onto the valley floor, as low as 282 feet below sea level.

Why are the Death Valley ephemeral streams and seasonal lakes so salty? After all, the crags that reach toward the skies, ringing the hot desert floor, are no different than most rocks in the western United States. They are made of common minerals like feldspar and silica; they erode with the violent wind and rainstorms; and gravity pulls the minerals down to what should be the sea — except, there is no sea. Here, the lowest point around happens to be the valley flats, not the Pacific. So the naturally occurring salts sit in the basins, accumulating year after year, century after century. Faults may quake, and springs evolve, but water sucked from a deep aquifer will be infiltrated by as many types of salt as there are chemists to measure them. These chemists report that conductivity varies wildly, from 5,000 to 50,000 micro Siemens per centimeter. It’s tough water to survive on.

Still, despite these bitter waters, animals do survive and even prosper. Invertebrates like the caddisfly, stonefly, beetles, and a specially adapted species of pupfish beat the odds. At Salt Creek, two types of vegetation dominate. Salt grass and pickleweed, salt-tolerant halophytes that also tolerate heat, carpet the weathered rock and line an ephemeral stream. During the winter months, the stream runs over a mile before disappearing into the permeable rock. The desert pupfish breed as waters warm in the spring; they establish and defend their territories in water that can be as shallow as one inch deep. Pupfish deposit their eggs in the sand, and a few successfully retreat to the spring head when summer bakes the pools away. Those survivors wait through the endless hot days of 125 Fahrenheit with little relief, even at night.

FROM THIS GENERATION TO THE NEXT

In Death Valley, the National Park Service takes a keen interest in the health of local watercourses, precious as they are. The four-year-old environmental education program Recreational Outdoor Campaign for Kids through Study (ROCKS) was exploring ways to empower youths to protect our streams. These three-day, two-night residential programs bring kids from urban, economically challenged areas to Death Valley, where they learn to set up tents, read the geological history of the Earth in its rock layers, and explore the ecology of fragile desert systems. It’s often the first time the kids see the Milky Way or touch a live fish. The program, based in experiential learning, focuses on the sciences, with an emphasis on geology, astronomy, and ecology. Salt Creek is just one place they visit in an action-packed trip to their national park.

Handling pupfish, tasting salt on the valley floor, and sketching rock layers are tactile ways to connect children with the desert, but educators wanted to participate in something that held significance beyond the park as a classroom. That’s where the Stroud Water Research Center’s Leaf Pack Network® entered the ROCKS program. It was a chance for the kids to do some service learning and to contribute to a nationwide database that assesses stream health.

In Death Valley streams, biodiversity is relatively low. Caddisflies dominate the count of invertebrates in the leaf packs, regardless of plant species or habitat characteristics, but we are establishing seasonal trends in invertebrate numbers. For example, in the dead of winter, caddisflies tend to be the only invertebrate species in Salt Creek. As March waxes, diversity increases. This change may represent the coming of spring, with both higher temperatures and additional food sources enabling the seasonal pupfish dance. These trends may be a way to measure the effects of climate change here in Death Valley over the next 50 years. The kids from Los Angeles and Las Vegas are playing a significant part in monitoring how the ecosystem as a whole responds to a warming climate.

Death Valley National Park is excited to take part in the Leaf Pack Network®, and the Education Department looks forward to supporting stream health measurement everywhere. In between leaf packs, they will be pulling up front-row seats to the most competitive dance around: the little Salt Creek pupfish, defending their territories with pride.

Outreach

Outreach

An Evening in Review: Wild & Scenic Film Festival

By Diane Huskinson

On Thursday, February 24, the 4th Annual Wild & Scenic Film Festival brought together nearly 300 people ready to be inspired by a series of environmentally themed short films. Hosted by Trail Creek Outfitters and Stroud Water Research Center and sponsored by local businesses with a passion for the environment, the nationally acclaimed traveling film festival grabbed audience members with breathtaking views, rare images of exotic flora and fauna, and staggering statistics. In so doing, it also challenged them to engage in stewardship activities.

The evening was a feast for the eyes and the palate, but even more so for the soul, as attendees learned how every step they take can be one step closer to conserving, protecting, and in some cases restoring our world’s most valuable resources. Among those resources is Stroud Water Research Center’s mainspring, freshwater, which was a recurring theme throughout the evening. Not only did many of the films pay homage to and underscore the need for life-sustaining water systems, but all proceeds from the festival benefited the Center.

The Majestic Plastic Bag, narrated by Jeremy Irons. This “mockumentary” drives home how plastic bag pollution imperils our waterways.

The list of award-winning animations, documentaries, and independent films featured everything from water-loving dogs splashing to the beat of reggae-inspired tunes by Matisyahu to a mock-nature documentary of a plastic bag’s journey from supermarket to sea.

Fate cast a special connection between Stroud Water Research Center and one of the films only days prior to the festival. One Percent of the Story featured interviews with business owners who, as members of 1% for the Planet, have pledged 1 percent of their sales to a network of environmental organizations committed to fostering a healthy planet. This February, the Center was accepted into that network of possible recipients for its advancement of knowledge and stewardship of freshwater through research, education, and global outreach. As it happens, national sponsor Patagonia, Inc. is one of the founding members of the alliance, and Sven Shiers from Patagonia was in attendance.

John Gilmartin, Chadds Ford, Pa., attended the festival with his wife and commented, “We live very close to the Brandywine River, so this really hits home. It’s a great event, great beer, great people. The films have been awesome.”

One film in particular, Witness, which featured stunning and convicting snapshots from dedicated conservation photographers, captured Gilmartin’s interest: “Our son is in school now, and he is interested in film and the whole idea of promoting conservation through film. I hope he will be able to attend next year,” he said.

To complement the evening’s entertainment, attendees were treated to the savory culinary creations of local favorite Talula’s Table, beverages by Victory Brewing Company, including their newest beer, Headwaters Pale Ale, and raffle prizes from Trail Creek Outfitters and Stroud Water Research Center.

Generous support from sponsors — especially premier sponsor Exelon — made the event possible. National sponsors included Patagonia, Inc., Clif Bar & Company, Osprey Packs, Inc., Klean Kanteen, and Grist. Local sponsors included Trail Creek Outfitters, Victory Brewing Company, Talula’s Table, Exelon, Kennett Square Environmental Council, and Nason Construction, Inc.

Stroud Scientists and Educators Present

Our ability to disseminate our findings to a broad audience allows us to increase awareness and create a public dialogue centered on the protection, preservation, and restoration of watersheds everywhere. It’s for that reason that our scientists and educators engage in both scientific and public forums to share their findings. The following highlights recent presentations.

USING CYBERLEARNING TOOLS AND PLACE-BASED EDUCATION TO PROMOTE SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY, ENGINEERING, AND MATH (STEM)

Stroud Water Research Center’s Education Department, led by Education Director Dr. Susan Gill, has had a busy first quarter of 2011 attending an American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Meeting in Washington D.C., an Innovative Technology Experiences for Students and Teachers (ITEST) Summit in Arlington, Va., and the Conference on Cyberlearning Tools for STEM Education (CyTSE) in Berkeley, Ca. These activities allowed the Center to share recent developments in the National Science Foundation–funded project Model My Watershed®. The project is a place-based modeling tool that uses an online, hydrologic, visual model and authentic data that allow students to see how runoff impacts their neighborhoods and their watersheds. Users can delineate the boundaries of their watershed; gauge the influence of environmental parameters on local hydrology; and examine the impacts of landscape alterations to hydrology in their own neighborhoods.

Model My Watershed® is being implemented in six schools in Southeastern Pennsylvania in the Schuylkill River watershed. Half of the schools lie within Philadelphia, while the others are from suburban or exurban areas. Each school engages a science and a math teacher who coordinate instruction to reinforce content across two subject areas. The project is reaching approximately 300 students.

LEAF PACK AND WATERSHED TOUR™ WORKSHOP AT REGIONAL CONFERENCE FOR NATIONAL SCIENCE TEACHERS ASSOCIATION (NSTA)

In collaboration with LaMotte, Stroud Water Research Center educator Christina Medved led two workshops at the regional NSTA conference in Nashville last December. Presenting to a packed room, teachers from Tennessee, Florida, Ohio, Alabama, and Missouri — just to name a few — learned about this unique way to study water quality. Participants learned about the basics of stream ecology, the river continuum concept, where along the stream continuum leaf packs naturally occur, and how to use leaf packs and macroinvertebrates as biological indicators. Teachers also learned macroinvertebrate collection techniques, identification, and data analysis via hands-on activities that could be replicated in the classroom.

INTRODUCING THE PRINCIPLES AND PROCESSES OF EARTH’S CRITICAL ZONE TO TEACHERS, INFORMAL EDUCATORS, AND ACADEMICALLY AT-RISK YOUTH

Stroud Water Research Center educators meet weekly with fourth and fifth graders in the Greenwood Science Club in Kennett Square, Pa. to help them explore the critical connections between the water cycle and the soil. The effort is part of the Center’s National Science Foundation–funded Critical Zone Observatory (CZO) education activities. Students are engaged in science-focused art activities, making rain fall on handmade watersheds and getting dirty working with soil. This educational effort aims to make understanding the processes that link water, soil, and atmosphere more accessible to general audiences.

DNA BARCODING

Stroud Water Research Center scientists recently published a study that demonstrates how the use of DNA barcoding of aquatic macroinvertebrates can enhance our understanding of stream invertebrate communities and water quality. DNA barcoding is a way to use a short genetic marker to identify an organism to a particular species.

At the Stroud Center, scientists are using DNA to identify fish from Costa Rica and macroinvertebrates from Pennsylvania and California streams. Invertebrate taxonomists at the Stroud Center identified 88 species using standard microscopy and visual determinations, and they identified 150 species from the same samples using DNA barcoding. These results suggest that there are cryptic species and groups of insects (midges) that are difficult to visually identify. The data add to the international effort by the Consortium for the Barcode of Life (CBOL), which aims to generate a unique genetic barcode for every species of life on earth.

Read the DNA barcode study

Read more about the International Barcode of Life (iBOL)

COUPLING THE CARBON CYCLE BETWEEN LAND, OCEANS, AND ATMOSPHERE

A recent paper by Stroud Water Research Center scientist Dr. Anthony Aufdenkampe and colleagues published in the Ecological Society of America journal Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment describes how rivers and other inland waters link water, carbon, and mineral cycles that occur on land, oceans, and atmosphere. They emphasize that rivers and other inland waters receive, transport, process, and return carbon to the atmosphere in amounts that are similar in magnitude to the net ecosystem carbon balance of the terrestrial ecosystems in their watersheds. They further point out that burial of carbon in sedimentary deposits in rivers and other inland waters is greater than the burial of carbon in the oceans. They conclude by noting that human-accelerated chemical weathering of minerals in watersheds and the export of major ions influences coastal-zone acidification.

Download a copy of the article

CHRISTINA RIVER BASIN CRITICAL ZONE OBSERVATORY

The Christina River Basin Critical Zone Observatory (CRB-CZO) is an observatory funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and established to study chemical, physical, and biological interactions that shape the earth’s surface. The observatory is led by a collaboration of researchers at the Stroud Water Research Center and the University of Delaware (UD). The critical zone is defined as the terrestrial layer extending from the treetops through to the groundwater and into stream networks. The group is working to quantify the impacts on the carbon cycle of humans as geological agents. Field sites are located throughout the Christina River Basin in Pennsylvania and Delaware at areas that vary in land uses from forested to agricultural to development-influenced watersheds.

In December, Dr. Anthony Aufdenkampe and a small contingent from the CRB-CZO attended the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco. Aufdenkampe presented results from his work on understanding how rivers transport and process carbon and to what extent carbon dioxide outgassing from the global collective of rivers is dominated by tropical river outgassing.

In March, Dr. Olesya Lazareva, CZO post-doctoral candidate working at UD and at the Center, accompanied Dr. Donald Sparks, Delaware Environmental Institute Director at UD, to an event in Washington D.C. to showcase UD research on Capitol Hill. Together they gave a presentation highlighting the importance of the continuous, long-term collection of environmental data and illustrating how recent developments in open-source hardware and software platforms could transform the ability to deploy sensors, field instruments, and other electronic “eyes and ears” to unprecedented levels.

HOW TO GARDEN FOR RAIN

Stroud Water Research Center, along with Transition Town Media and the Environmental Advisory Council of Media, Pa., co-sponsored “Gardening for Rain,” a presentation on February 22 by Vivian Williams, educational consultant with the Stroud Center, on rainwater harvesting. Addressing the practical application of rain barrels, rain gardens, and pervious pavers, Williams explained how gardening can reduce stormwater flooding and runoff into freshwater streams, a hot topic for Media residents who are seeking new ways minimize stressors on their watershed.