Stroud Scientists at Work

Rivers Are Not Pipes

Advancing Science Using Cutting-Edge Technology: An Interview with Engineer Shannon Hicks

By Jamie Blaine

Shannon Hicks talks animatedly about her work, her fingers dexterously putting together and pulling apart the tiny electronic parts on the table beside her. I am not surprised to learn that she was trained as a classical pianist from the age of 5. In high school she was offered more college scholarships in music than in engineering. Now, however, she is an electrical engineer whose job is to create complex water-monitoring equipment out of inexpensive components you can buy at Radio Shack.

She is doing this work as part of the collaboration between Stroud Water Research Center and the University of Delaware on the Critical Zone Observatory (CZO) project in the Christina River Basin. This is no small undertaking: With a $4.3 million grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF), researchers from both institutions seek to understand how soil erosion impacts climate change.

Over the last several centuries, humans have converted the 565-square-mile Christina River watershed from “Penn’s Woods” to a residential, agricultural, and industrial region that is home to more than 400,000 people. In the process, they have released vast amounts of minerals and organic sediments into streams and rivers, which in turn transport them to the ocean. The CZO team wants to know how the minerals and carbon interact, what effect that interaction has on carbon sequestration from the atmosphere, and how human activities have altered the natural processes.

To do that, they must take both a bird’s-eye and a worm’s-eye view — simultaneously studying the watershed as a single whole while monitoring its activities in minute increments of time and space.

Enter Shannon Hicks, whose job is to create the equipment to do so — and to do so cheaply.

HOT SPOTS AND HOT MOMENTS

“Up to now,” said Hicks, “people have been sacrificing their science due to the limitations of hardware.” Because conditions vary widely across the watershed, it can be misleading to generalize data from a handful of sites. Conversely, some events happen sporadically, even uniquely, and if you are not there to record them, you may misinterpret what is really happening. To capture these “hot spots” and “hot moments” requires a lot of equipment.

“By placing sensors in as many places as possible and having them record and transmit data as often as possible, we maximize our coverage of the watershed,” Hicks said. “It will change not just the quantity — but the quality — of our data. We will get feedback on the health of the whole network almost literally as it is happening.”

In the past, she added, “there was no way the Stroud Center could afford to do what we can do now, primarily because the cost of the hardware was prohibitive.”

That is no longer true.

HOME INVENTORS AND OPEN SOURCING

In the last few decades, the world of electronics has exploded. Thousands, perhaps millions, of inventors in laboratories, offices, and basements around the world are constantly creating new electronic devices, building prototypes, and making their designs available to the public through a process known as open sourcing. “With open sourcing and home inventors,” said Hicks, “new stuff is coming out all the time. It is faster and cheaper, and it has more memory than ever. Now you can do just about anything you can think of…, and you can do it with parts you pick up in an electronics store. I recently found some parts I needed on eBay.”

Nor are the inventors necessarily engineers, or even scientists. Artists, performers, hobbyists and all kinds of other people are dreaming up platform designs for their own work. There are a lot of great ideas out there, said Hicks, and they tend to be simple and cheap to build. For example, she said, “we will soon use radio transmitters, not wires, at a cost of $20, not $2,000, and have 20, 30, 40 sensors constantly transmitting data to computer screens.”

There is so much information available and so many different ways to build something, she added, that it can be overwhelming. “So I fill my head with stuff and let it roll around until ideas come together…sometimes after weeks or even months.”

THE MAKING OF AN INVENTOR

For Hicks, rolling ideas around and finding innovative solutions to complex problems began in childhood, when she dismantled her Christmas presents to see how they worked. Later she created a device that made bat sounds accessible to the human ear and a camera she mounted on a kite to take aerial photos, and she used early GPS modules to assemble vehicle-tracking devices several years before they came on the market. In high school she built antennas for a ham radio that enabled her to talk to an astronaut in space from her car. In college she worked in a research lab, where she was told, simply, “If it doesn’t exist, build it yourself.”

As the Stroud Center’s technology guru, that’s exactly what she does. “Not only does my job give me the freedom to innovate, but Anthony [Aufdenkampe, assistant research scientist at the Stroud Center and CZO co-principal investigator] has given me the rope to explore new things,” she said.

One of her first ideas was a “self-healing mesh wireless network.”

“When I first told people that it was possible to build a logger and radio transmitter for $100, they told me I was crazy. But we’ve done it.”

PUBLIC ACCESS

Open sourcing gives the Stroud Center access to the incredible wealth of ideas, information, and innovation on the Internet. It will also make the Stroud Center’s knowledge available to the public. While scientists have traditionally been proprietary about their data, the CZO requires program participants to build their platforms for public use, to make their data available in a timely manner, and to share their hardware designs. “The CZO project is about cooperation rather than competition,” said Hicks, “and because it is a two-way street, we will get input as well as share output.”

The sharing will not just be with other scientists. Hicks’ face lights up when she talks about working with the Education Department to build simplified versions of the platforms for kids. “They can build simple boards, sensors, and transmitters, program them, and take their own data,” she said. “How exciting will it be for them to go from a bag of Radio Shack parts to collecting live data in half a day?”

Beyond Naked: A New Study of Life “Invisible”

By Diane Huskinson

The River Continuum Concept (RCC), the idea that from headwaters to mouth a river changes in its physical characteristics which, in turn, influences the river biology, brought worldwide attention to the work being done at Stroud Water Research Center when Robin L. Vannote and some of his fellow researchers published the concept in 1980. Now the Stroud Center’s scientists are advancing its predictions that downstream communities capitalize on the inefficiencies of upstream communities. They’re also making a few new ones using some of the most sophisticated and groundbreaking tools and techniques to hit microbiology since Anton Van Leeuwenhoek invented a microscope that made seeing microscopic life possible for the first time more than three centuries ago.

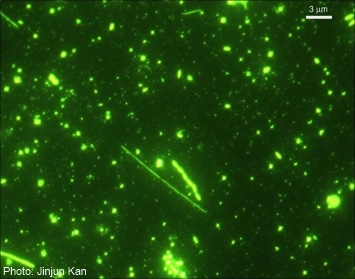

Stroud Center scientists Lou Kaplan and Jinjun Kan have been awarded a grant through the National Science Foundation (NSF) that will allow them to investigate the mysterious interplay in meta-ecosystems, which Kaplan defines as “a series of stream ecosystems connected by the flow of water and the components carried by the water.” Those components include dissolved organic matter (DOM), which are organic chemicals that flow off the landscape, dissolve out of leaves or algae, or are excreted by organisms into stream water.

Kaplan and Kan will work in collaboration with Robert Findlay of the University of Alabama and Jen Mosher, who will join the Stroud Center staff when she leaves Oak Ridge National Laboratory in early 2012, to study the influence of DOM on the structure and function of the communities of microorganisms that live in streams and rivers.

They’ll work in three forested headwater stream ecosystems: White Clay Creek (WCC) in the Pennsylvania Piedmont, Río Tempisquito in the Cordillera de Guanacaste of Costa Rica, and the Neversink River in the Catskill Mountains of New York. From a range of stream sizes within those watersheds, they’ll collect, detect, and analyze population structures of microorganisms, rare and common, while also evaluating the DOM that serves as a food source for these communities in an effort to discover a link between the upstream-downstream variations in DOM and microbial communities as the RCC predicted.

New tools like ultrahigh-resolution mass spectrometry, high-throughput DNA sequencing, and stable isotope probing will enable the team to answer questions that have eluded stream ecologists in the three decades since the RCC was published.

It’s also an opportunity for the Education Department to help shed light on life beyond the naked eye by interpreting results to the general public and working with K-12 teachers and students in programs planned for the watersheds in Pennsylvania, New York, and Costa Rica.

Kaplan says, “Biodiversity on Earth is most rich at the microbial level. Microbial life we can’t see with the naked eye performs biochemical processes that shape the world we can see. With this study, not only will the scientific community better understand life in streams, but so will students, teachers, and the public, and that’s the essence of Stroud science.”

Stroud Educators at Work

Moods of the Trekkers

By Jamie Blaine and the Brandywine Trekkers

On June 14, 2011, eight students from Coatesville-area high schools set out on a trek that took them, on foot and by canoe, down the Brandywine River from its headwaters in northern Chester County to its mouth at Wilmington. Their goal was to learn about the importance of their river, understand how it connects all the diverse communities through which it flows, and become the agents for educating the public about the need to protect it.

The trek began with a hike to the Brandywine’s source, a small spring on a farm just outside Honey Brook, Pa., where they drank the sweet-tasting water that earned the place its name. They visited Lukens (now ArcelorMittal), the oldest operating steel mill in the U.S., where they learned that Soviet nuclear missile silos targeted the Quaker-owned plant during the Cold War because it was a large producer of munitions. As a result, there are several bomb shelters in and around the city of Coatesville.

When the trekkers paddled across the Pennsylvania/Delaware line, they passed from a state which began the process of abolishing slavery in 1780 to one that did not fully desegregate its public schools until 1968, 14 years after the U.S. Supreme Court had declared them unconstitutional. They toured the Hagley Museum, site of one of duPont’s earliest gunpowder mills, and camped at Hoopes Reservoir, which is filled with Brandywine water even though it lies in the Red Clay Creek watershed. Along the way they took samples to assess the health of the water that Wilmingtonians drink.

They recorded their experiences in photographs and journal entries, which will be on display in public exhibits around the watershed this fall. They also committed themselves to lead a community restoration project on their return.

Created by the Stroud Water Research Center, in partnership with the Coatesville Youth Initiative, the Brandywine Conservancy, Chester County Parks, Chester County Water Resources, Chester County Conservation District, and the City of Wilmington, the trek was a full-immersion experience focused on (a) educating the students about the importance of the river and its water; (b) teaching the students about tools to become stewards of the river; (c) building a sense of teamwork and community responsibility among them; (d) providing an intense outdoor experience; and (e) showing them that they are intimately connected — both now and historically — to all the people, communities, and natural life in the watershed.

The trek challenged the participants physically, intellectually, and emotionally, and their words reflect their many moods along the way.

APPREHENSION

“The things that I’m most worried about are the food and where we use the bathroom. I say this because I’m a picky eater and I never went to the bathroom outside.” (Kourtne)

DELIGHT

“It’s amazing that we are so close to the city and it’s so quiet. The sounds of the birds and the water … oh, man, I could listen to this all day. The air is so nice I feel like I can actually breathe!” (Jess)

NOSTALGIA

“Fishing and camping make me miss the old time, when my brother, my mom and dad, and I would all go camping.” (Sarah)

SKEPTICISM

“It seems somewhat odd not bringing soap on the trek.” (Noah)

INSIGHT

“If you really sit and look deep inside nature and listen, it sounds and looks beautiful … besides all the nasty bugs.” (Shaquaia)

CONTENTMENT

“I caught three fish today. Even though they were small, they were still something to me.” (Bruce)

WONDER

“I’m learning a lot about life outside of our city. I’m learning how amazing God is. … You would never imagine how peaceful this world could be. It even smells clean. Pine sol clean.” (Jewel)

AGGRAVATION

“At this point I am very aggravated! I’m not aggravated at anyone in particular. I just feel overwhelmed. It feels like a train just hit me out of nowhere and I’m wiped out. But this is a great life lesson for me.” (Jess)

AMBIVALENCE

“At this very moment I feel kinda like free. It’s the feeling that you’re in a different world, away from cars, streetlights and the normal noises of the city. Through all the feeling of freedom, I do miss my home.” (Sarah)

RESILIENCE

“We had a little difficulty in the canoe, but we got better. Quaia and I tipped over in our canoe. It was so much fun! Chris said we popped out of the water smiling.” (Kourtne)

FEAR

“Last night was scary and hard. We woke up at 1:30 a.m. to a thunderstorm, and lightning followed. We were directly under it, too. At some points the light would flash with the thunder directly after it.” (Veronica)

LONGING

“I am getting a little homesick, so I have this thing where I look at the moon, and my family and I are closer together because we all have the same moon and the same stars.” (Shaquaia)

PEACE

“It feels like I am so far away from home. Like I’m on a different planet with no worries and especially no stress! I feel like I can do anything and be my goofy self and not get judged or made fun of.” (Jess)

ENDURANCE

“Now we get to hike with extremely heavy bags. I see what my sister has to go through when she goes to drill with the National Guard.” (Veronica)

EXCITEMENT

“Oh, hey. Today was a great day. We canoed today. So exciting! At first it was blood rushing, but towards the end I got tired. I loved it, though.” (Jewel)

DEJECTION

“So I was going to leave this morning, but I don’t know, I just thought that I should finish what I started. I did have fun today. I’m not going to lie. … I just can’t believe I’m this homesick.” (Sarah)

RESOLVE

“There is not a thing I would change about this opportunity, even though I am not your average nature girl. I hate the outside, bugs and everything else that comes with nature. But I have a new saying — “don’t ever say you can’t” — because there is nothing that you can’t do.” (Shaquaia)

UNDERSTANDING

“The river has an awesome history … and I didn’t know that it has this beauty about it, that you don’t fully understand until you have drunk it, swum in it, fished in it, canoed in it, and of course just plain old been around it. Until you really get to know the Brandywine you can never truly appreciate it. Take it from me.” (Sarah)

APPRECIATION

“The things I appreciate most about the river are its beauty, being our source of drinking water, being a shelter for many animals, and its length.” (Bruce)

TRUST

“The river is so fun to be on. The scenery is amazing! Even though the obstacles we had to get through were a tad vicious, we did it with teamwork. That is definitely a necessity [on] this trek. We would get nowhere without teamwork.” (Jess)

RESPONSIBILITY

“I’m learning to appreciate the beauty of the river. See how important we are to keeping the Brandywine healthy. Having such an important landmark around most of my life has never been so amazing as it is now. God amazes me more and more, I swear.” (Jewel)

SELF-AWARENESS

“I like this river because you need patience to canoe on the Brandywine. You also must have teamwork, and the Brandywine River can help you accomplish it. I love this river because it builds concentration and skill with your partner. I love the Brandywine because it opens new eyes for people who only drive on the pavement. It also gives self-confidence.” (Noah)

CONFIDENCE

“I’m pretty used to doing a dissolved oxygen test now without the fear of acids burning a hole in my hand.” (Veronica)

SELF-CONFIDENCE

“This was a really good experience. It taught me a lot about myself, others and nature. I learned that I could do anything if I try. … My family and I thought I would never make it out here, [that] I would go home a couple hours into it, but I proved them and myself wrong.” (Shaquaia)

Events

The Event of the Season: A Sustainable Feast

By Jamie Blaine

At a dinner featuring the finest producers of local food, wine, and beer, Bern Sweeney emphasized an often-overlooked common denominator: “The main ingredient of everything you eat and drink this evening,” said the Stroud Water Research Center’s director in his welcoming remarks, “is fresh water.”

Fresh water was also on the minds of Lynn Biddle and Kay Dixon, the Stroud Center’s development staff, who were in charge of the annual affair. Their concern, however, was with the heavy downpours that had appeared suddenly and periodically throughout the day and the forecast for evening thunderstorms. But for the second time in the three-year history of the feast, the weather broke just before the event began, and the guests arrived to a clear evening with spectacular views across the rolling fields of Applestone Farm into a streaked purple sky and a setting sun. And so the 125 dinner guests turned from concerns about bursts of rain to the flow of Va La’s wines, Victory’s beers, and Waywood’s beverages.

It was indeed a feast. Sponsored by Northern Trust, with a menu created and prepared by Talula’s Table, the event featured the beef of former Stroud Center board member Bill Elkins and his Buck Run Farm, soup made from Phillips’ mushrooms, vegetables grown by H. G. Haskell, greens from SunnyGirl Farm, and sweets from Éclat Chocolate. Julia Loving arranged the flowers on the tables, and R – P Nurseries provided the plants that lit up Michael and Anne Moran’s rebuilt barn, which sits on the edge of the Pennsylvania Hunt Cup course just outside Unionville, Pennsylvania.

The purpose of the Sustainable Feast is to provide an entertaining evening and a sumptuous meal that highlights the quality of local food producers and emphasizes the relationship of sustainable agriculture, healthy food, local production — and the clean fresh water on which they all depend.

Our Generous Sponsors

This spectacular evening, the proceeds of which benefited Stroud Water Research Center, was made possible by the following sponsors: Applestone Farm, Inc., Buck Run Farm, Éclat Chocolate, Flower arrangements by Julia Loving, Northern Trust, Phillips Mushroom Farms, R – P Nurseries, Restrooms Remembered-Mobile Lavatories, SIW Vegetables, SunnyGirl Farm, Talula’s Table,Va La Vineyards, Victory Brewing Company, and Waywood Beverage.