Melinda Daniels: Building New Ideas on Old Foundations

By Jamie Blaine

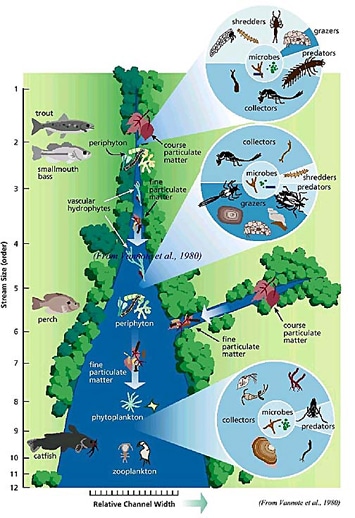

Perhaps the most important paper yet written on freshwater ecosystems had its origins at Stroud Water Research Center. Published by then-director Robin Vannote and his colleagues in 1980, “The River Continuum Concept” (RCC) proposed a new way of looking at stream systems. Over three decades later, it remains the most often cited paper in its field. So, when a recent article authored by an incoming senior scientist is titled “The River Discontinuum,” people notice. Moreover, the current work of Kansas State University Professor Melinda Daniels, who will join the Stroud Center next month, concerns beavers, whose dams raise important questions about the natural state of rivers the RCC set out to describe.

Rethinking the Impact of Dams

In a recent interview, Daniels called the RCC a “game-changing paper” that had generated a great deal of research and new thinking — including spurring her graduate student Denise Burchsted to think about how beavers actually disrupt the free flow of water and sediment and how the dams they build affect a river’s ecosystem. Beavers were once ubiquitous across North America, with an estimated 60-90 million here when the first Europeans arrived. Their pelts created vast fortunes until trapping decimated their numbers, and human development permanently destroyed much of their habitat.

While beaver dams aren’t much in the news these days, man-made ones certainly are, and many scientists believe their removal will restore rivers to more natural and healthier states. But if we truly seek to return our waterways to a more “natural” condition, Daniels argues, we should study the role beavers play in “generating heterogeneity within a river network and how their small dams impact the larger ecosystem processes.”

Joining the “Think Tank”

Daniels will occupy Denis Newbold’s former laboratory, and she follows in that lab’s tradition of interdisciplinary work. “I am a geographer, a geomorphologist, a hydrologist in part,” she said, “but I really think of myself as a river scientist. I suppose my real strength is being a scientifically literate bridge between colleagues who specialize more closely on one area.”

Daniels’ interest in landscape-wide physical changes to river systems complements much of the recent work at the Stroud Center, including sediment transport, hydrology, and nutrient processing studies, as well as Anthony Aufdenkampe’s work on huge river systems around the world. It also builds on the Stroud Center’s roots, where the RCC evolved from Ruth Patrick’s broad ecosystem approach to watersheds and Luna Leopold’s studies of physical changes across the entire river system.

Like many future river scientists, Daniels spent her childhood summers on the water, in her case, the Russian River in California, fishing, swimming, and boating. “I just always loved being active outdoors,” she remembered. Her husband, Rob, is also a geographer who has worked for land trusts and state agencies on conservation easement and geographic information systems. He arrives this month to work on the house they bought in Unionville. Daniels will come with their son Logan (5) and daughter Lily (4) when school ends in May.

“I like to develop interesting ‘big questions’ that cross disciplinary lines,” said Daniels of her new role. “I see the Stroud Center as a kind of river ‘think tank,’ and I am thrilled at the chance to work in such an environment.”

Introducing Our Watershed Restoration Group

By Diane Huskinson

When Matthew Ehrhart and David Wise first visited Stroud Water Research Center about 20 years ago, each of them imagined it would be a dream come true to work at the Stroud Center with “cool, smart people doing interesting things,” said Wise.

“At the time,” Ehrhart explained, “I didn’t even realize how big of a role Stroud Water Research Center played on the national/international stage of freshwater science.” But Ehrhart did take note that “Stroud was far ahead of the curve in understanding what goes on in streams. “I was working as a consultant through the regulatory process for stream assessment and restoration, and Bern [Sweeney, the Stroud Center’s director] was just a storehouse of knowledge. So the Stroud Center has long been on my fantasy employer list.”

Now that fantasy is reality for both of them. In January, the Stroud Center launched the Watershed Restoration Group to utilize the Stroud Center’s groundbreaking freshwater science to develop, research, implement, and monitor restoration projects throughout Pennsylvania and beyond.

BRINGING OUR MISSION FULL CIRCLE

Matthew Ehrhart, former Pennsylvania executive director of the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF), joined the Stroud Center to head the Group, and David Wise, also formerly of CBF, accompanied him to serve as the watershed restoration manager.

Ehrhart holds a Master of Engineering degree from Penn State’s Engineering Science Program. After working as an environmental scientist for LandStudies, Inc., he worked as a watershed restoration consultant before joining CBF, where as executive director he was responsible for overseeing a multimillion-dollar agricultural restoration initiative in Pennsylvania.

Wise received his Master of Science degree in Land Resources from the University of Wisconsin-Madison Institute for Environmental Studies. After serving as an environmental science instructor at Lancaster Mennonite High School, he joined CBF — first as a biologist and then as the Pennsylvania watershed restoration program manager.

Together, they will bring the Stroud Center’s mission full circle by sharing knowledge of best management practices (BMPs) and helping landowners, stakeholders, and the general public to implement them.

Stroud Center Director Bernard Sweeney said, “We’re excited Matt and Dave are on board. By using our research to create green infrastructure, the Watershed Restoration Group will help communities prepare for a brighter future for our water.”

HITTING THE GROUND RUNNING

The Watershed Restoration Group has already secured three grants.

One is provided through the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF), with funding from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, and Altria Group. It will allow the Group to develop a project to help farmers implement BMPs to address common water quality issues by providing technical assistance and advancing nutrient trading. Partners include more than a dozen public agencies and private groups, and an estimated 27 farms in Lancaster and surrounding counties will participate. A companion grant, provided by the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection’s Growing Greener Program, will expand these efforts to additional farms to address water quality impairments.

Another project supported by a grant from NFWF, with funding from the EPA and U.S. Forest Service, will demonstrate low-cost alternatives to existing buffer reforestation methods, which can be expensive and have shown mixed results. Methods to be demonstrated include natural regeneration, direct seeding, and live staking.

The Last Train

Frank Klein’s Remarkable Journey from Wartime Refugee to Stroud Water Research Center

By Jamie Blaine

To hear Frank Klein tell it, almost everything in his life, from getting a Ph.D. in chemical engineering to meeting his wife to 15 years as a volunteer at Stroud Water Research Center, happened “more or less by accident.” The reason quickly becomes clear to an interviewer: Klein has approached his long life with a sense of wonder that keeps him ever open to the unexpected.

He has had to. Born in the Sudetenland in 1929, Klein and his family left Czechoslovakia nine years later aboard the last train the Hungarian fascists allowed across their border. From that point on, the once well-to-do Jewish family stayed one step ahead of the Nazis until they sailed into New York Harbor in the spring of 1941. They spent the first 10 months in Paris before fleeing to St. Jean de Luz in the Basque country. From there, they moved to Marseilles, a refugee-filled city controlled by the puppet Vichy French government that Klein described as “an amalgam of heaven and hell.” Paid smugglers took the family on foot across the mountains into Spain, where they were promptly arrested. Frank’s parents were sent to prison, and he and his sister were placed in an orphanage, but the family was reunited after several days and deported back to France. They subsequently escaped, again through Spain, and then on to Portugal, where they boarded a ship bound for Cuba and finally to New York City. Thirty-two months after their long and twisting journey had begun, the Klein family settled in to become Americans.

Klein tells this story in a memoir he wrote a few years ago, in which he describes his travels through the eyes of the small boy he then was. Although his family spent years on the run, displaced, transient, and uprooted, Klein experienced the dislocations with as much wonder as fear. Each new city presented him with new things to see, and prodded by their remarkable mother, the family visited museums, tried exotic restaurants, and never missed a chance to experience something new. They were not going to allow their often desperate situation to dominate their lives.

After earning his Ph.D. in chemical engineering from the University of Michigan in 1955, Klein spent his entire career with DuPont, where he instituted and then managed the company’s pioneering chemical-process safety program for its paint-manufacturing plants around the world. He retired in 1992 and began volunteering at the Academy of Natural Sciences. Four years later, he applied for a volunteer position at the Center.

“Bern Sweeney said he’d be happy to have me here,” remembered Klein. “But there’s just one thing wrong,” said Sweeney, eyeing Klein in his suit and tie. “You need to stop wearing good clothes.”

He has worked ever since in the Ecosystem Processes laboratory, doing what he calls “fall-in work: we measure what falls into streams from the trees, and we track it over the years,” as well as preparing and weighing samples, washing bottles, and “occasionally doing some work that requires the use of my mind.”

In general, said Klein, reflecting on the extraordinary journey that has brought him to the quiet laboratory on White Clay Creek, “my work here is pretty routine. I like that.”

Two Evenings in Review: The 6th Annual Wild & Scenic Film Festival

By Diane Huskinson

On Wednesday, February 27, and Thursday, February 28, fans of the nationally acclaimed Wild & Scenic Film Festival were once again treated to an evening or two of environmentally themed short films, locally made food and drinks, and fellowship with friends who share a passion for the earth that sustains us. Trail Creek Outfitters hosted the event, which sold out seats to both nights’ films, at the Chester County Historical Society. Proceeds benefited Stroud Water Research Center and The Land Conservancy for Southern Chester County.

CELEBRATING ACCOMPLISHMENTS

The theme for the festival’s sixth year, announced Brian Havertine of Trail Creek Outfitters, was “A Climate of Change.” Havertine said as he introduced the films on Wednesday evening, “I believe ‘A Climate of Change’ applies to grassroots organizations.” While the earth faces many challenges and there is much work to be done, Havertine stressed the importance of celebrating accomplishments, and so all of the featured films pointed to successes in environmental conservation and stewardship.

Stroud Water Research Center had a hand in one of those successes. The film “Public Lands, Private Profits: Too Special to Drill” tells the story of Wyoming’s Noble Basin, held in the public trust but threatened by natural gas drilling. The basin is a gateway to a region of rich wildlife and scenery that draws millions of visitors each year. But with the threat of gas mining looming, many feared the same consequences seen in other mined areas, such as decreasing wildlife populations, could befall the Noble Basin. Stroud Center scientists were asked to visit the area last year and help strategize with local conservation groups and concerned citizenry to reach an agreement that would be in the best interest of the basin. Ultimately, the Noble Basin was rescued via The Trust for Public Land, which organized the purchase of natural gas leases that will be donated back to the Forest Service and retired.

MAKING A DIFFERENCE

Another film that resonated with attendees was “How the Kids Saved the Parks,” a true story about a group of schoolchildren who, by making their voices heard, saved their beloved California state parks from being closed due to budget cuts. One boy commented, “I’m glad we saved this park because all the next generations of my family will be able to see it.”

“I learned that kids can make a difference,” another student said.

And a third: “I think I will always enjoy this park and never forget what I did to save it.”

The children’s story stood out to Marilyn Henry of Wenonah, N.J., who said, “The theme of success stories — it’s nice to see progress being made.” She and her friend Sharon Small of Kennett Square are recurring attendees of the film festival. Small added, “It’s so inspiring to see people are finding ways to care for their environment.”

The evening’s theme hit home when Stroud Water Research Center Director Bern Sweeney announced the Center’s new Watershed Restoration Group is working to implement watershed restoration programs throughout Pennsylvania and beyond.

The Wild & Scenic Film Festival was made possible by the generous support of national sponsors Patagonia, Inc., Sierra Nevada Brewing Co., Clif Bar & Company, and Mother Jones and local sponsors Exelon Generation, Dogfish Head Craft Brewery, Whole Foods Market of Glen Mills, Fig West Chester, FarmTable Gathering, Doe Run Farm, One Village Coffee – Specialty Roaster, Triple Fresh Catering, Galer Estate Vineyard & Winery, Terrain, Buck Run Farm, George & Son’s Seafood Market, and WH2P Marketing Communications.

Stroud Scientists and Educators Present

Stroud Water Research Center scientists and educators had a busy first quarter this year, sharing their work, exciting innovations, and knowledge.

Gill Speaks About Innovative Cyber Technology Tools

Susan E. Gill, Ph.D., was invited as a keynote panelist at the Life Discovery – Doing Science Conference on March 15-16. Sponsored by the Ecological Society of America, the conference highlighted leading science, curriculum design and implementation, and data exploration in environmental biology education. She also spoke about Model My Watershed® and WikiWatershed®, innovative cyber technology tools for watershed science education, at the Christina Basin Task Force on March 8 and at Cabrini College in the watershed citizenship class on March 12.

Newbold on Linking Upstream to Downstream

J. Denis Newbold, Ph.D., research scientist emeritus, gave a seminar, “Linking Upstream to Downstream: How Nutrients and Particles Spiral Through the River Continuum,” at the Annis Water Resources Institute, Grand Valley State University in Muskegon, Mich., on 8 Feb 13.

Metaecosystem Research Presented in Louisiana and Florida

Senior Research Scientist Louis A. Kaplan, Ph.D., and Researcher Jennifer J. Mosher, Ph.D., attended the Association for the Sciences of Limnology and Oceanography (ASLO) 2013 Aquatic Sciences Meeting on February 17-22 in New Orleans, where Mosher co-chaired a special session: “Microbial Mediated Retention/Transformation of Organic and Inorganic Materials in Freshwater and Marine Ecosystems” and gave an oral presentation she co-authored with Kaplan and Assistant Research Scientist Jinjun Kan, Ph.D.: “A Metaecosystem Approach to Investigating Bacterial Community and Dissolved Organic Matter Interactions in Three River Networks.”

Mosher was also invited to give a talk at the U.S. EPA Gulf Ecology Division in Gulf Breeze, Fla. titled, “Metaecosystem Approach to Investigating Bacterial Community and Dissolved Organic Matter Interactions in Three Distant Watersheds.” Additionally, Kaplan gave an oral presentation: “Coupled Geochemical and Biogeochemical Characterization of Dissolved Organic Matter From a Headwater Stream.”

Watershed Restoration Group Speaks to National Fish and Wildlife Federation, Plain Sect Audiences

Stroud Center Director and Senior Research Scientist Bernard W Sweeney, Ph.D., and Matthew J. Ehrhart, director of the Stroud Center’s new Watershed Restoration Group, gave presentations at the National Fish and Wildlife Federation’s Agriculture Networking Forum, while Watershed Restoration Manager David S. Wise gave a presentation on forested buffers to approximately 75 members of the Plain sect community.

Celebrating a Milestone

On April 11, 2013, Bern Sweeney marked 25 years as director of Stroud Water Research Center. He has steered the Stroud Center through good times and bad, championed our research and education programs, and advanced our reputation worldwide. Twenty-five years later, he still loves coming to work every day.